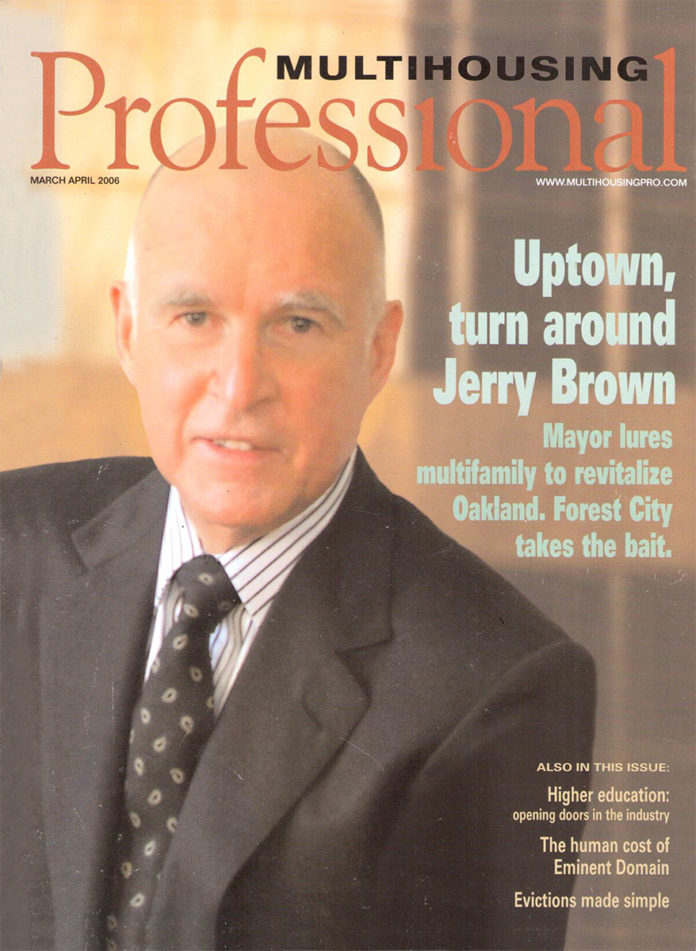

On a coast filled with dreamy, seaside cities, Oakland is more like a Midwestern industrial town dropped far from home. Mayor Brown points out, “most of the people who work downtown, live elsewhere. They dine and seek entertainment outside the city. For thirty years, downtown has been warehouses, lots and vacant buildings.”

Oakland has seen its share of challenges. So much so that six years ago the television news show, 60 Minutes did an expose on its worst, most poverty-stricken area along Martin Luther King Jr. Way. The unwanted attention created quite a stir; Oakland City Council stepped in and demanded a retraction from CBS. No such luck. Mayor Jerry Brown, however, exploited the opportunity to rally his cause, and add that the good Council was “in denial.” At the time, the mayor made the salient point that the real task would be to turn things around, especially things that garner national attention.

It turns out that in television-talk, the 60 Minutes episode was a grand case of foreshadowing, and the plot was only beginning to heat up.

The primary objective of Jerry Brown’s seven-plus years as mayor has been to dramatically change the city in line with his vision, “Downtown Oakland will be a lively, cultured, world-class neighborhood all its own. We are making Downtown the thriving core of our city, complete with the retail and entertainment that people currently seek elsewhere.”

“Oakland had a lot of empty space to fill,” Brown says. “To fill it, you need people to spend money which means bringing in private capital. Government does not build restaurants and, for the most part, doesn’t build houses. That’s done in the private sector, so you have to attract it. For 25 or 30 years, people weren’t investing in Oakland. Now they are. It’s dramatic.”

The basis of this revitalization has been deemed the “10k Initiative” by the mayor.

Brown says, “the initial idea was to build enough housing for 10,000 residents. By the end of the year, we will have approved enough units for 12,000 residents. There is no magic number. I thought 10,000 would be a good start. I wouldn’t mind 25k—along with all the restaurants, clubs and shops that would make downtown a vibrant place at all hours.”

“I was impressed by the notion of elegant density, the idea that the core of a city should be vibrant and busy, the plaza where all citizens come together; a city with great transportation like the BART system should maximize its potential. Instead of spreading out in a way that undermines the utility of our world class transportation system, residents should be able to walk out their door, get on a train and go to work. The connectivity, coupled with efficient use of space and sustainable building practice, is the wave of the future for cities like Oakland.”

It’s important to note that the first necessary change that occurred within Oakland was the passage of Measure X authored by Brown and supported by 75 percent of the voters, this legislation streamlined municipal departments and processes, and made the Mayor responsible.

With Measure X paving the way for movement, Brown has been busy with developers. Thus far, he’s attracted 62 new residential projects to downtown Oakland during his term. Seventeen of these projects are complete, adding 1,663 units to the city’s landscape. Fifteen projects representing 2,144 units are under construction; another 2,196 units spanning 20 projects have been approved; and another 1,366 units are in planning. Across the city, residential development is up 261 percent during his administration. Another 9,575 units are in process.

The latest of the developments to turn dirt is Forest City’s Uptown project. Brown says, “We’ve been trying to get this site developed for 25 years. Every day 70,000 people come downtown to work. Now they’ll be able to stay downtown and enjoy this part of the city like I do.”

Once the center of Oakland’s entertainment district, Mayor Brown said the site “had been the province of prostitutes and crack dealers for decades.”

Forest City’s new development converts an anchor holding downtown back into a sail propelling the city. The first phase of Uptown consists of 665 rental apartments, 9,000 square-feet of neighborhood-serving retail space, and a public park. Twenty five percent of Forest City’s units are designated affordable housing. The first units will deliver in September 2007, with completion of the first phase by the end of 2008.

The project, combined with the revival of the historic Fox Theatre, will also serve as the home of Jerry Brown’s School for the Performing Arts. The school, along with the regeneration of existing retail, is expected to spur the rebirth of Oakland’s Uptown neighborhood. Follow-up phases will include an additional 550 apartments and 20,000 square-feet of retail space.

“Forest City’s faith in Oakland’s viability as a location for a major investment is a major contribution to our town.” Brown adds.

Other developers and businesses are coming to town as well. Eight proposed high-rise residential towers are being planned. Dozens of stores, more than 40 restaurants and cafes, 25 nightclubs and bars and 14 new galleries have fueled a resurgence of nightlife in downtown Oakland.

For the first time in 30 years, a national grocer, Whole Foods, is opening a new store in downtown Oakland. Business tax revenues are up 52 percent and hotel tax receipts are up 28 percent. Visitors are spending $2.5 million a day in the city.

Brown, who acts as the Oakland’s developer-in-chief adds, “Oakland is a great place to do business. It’s got the best weather in the Bay Area, and is a mere train stop away from San Francisco. Get your applications in before I leave office.”