It was just a middle-school tennis match against a manifestly worse player, but I became overwhelmed with anxiety. Before we’d started, the most important thing was to win. But during the match, I just wanted to get off the court fast. Burping uncontrollably, afraid of throwing up, I hit balls out. I hit them into the net. I double-faulted. And I lost 6-1, 6-0. After shaking hands and running off the court, I felt immediate relief. My distended stomach settled. My anxiety relented. And then self-loathing took over. This was a challenge match for a lower-ladder JV position. The stakes were low, but to me they felt existentially high. I’d lost to the overweight and oleaginous Paul (not his real name), and the result was there on the score sheet, and on the ladder hanging on the locker room wall, for all to see.

This sort of thing—purposely losing matches to escape intolerable anxiety—happened dozens of times throughout my school sports career. My coaches were baffled. How could I look so skillful in practice, they wondered, and yet so rarely win a significant match?

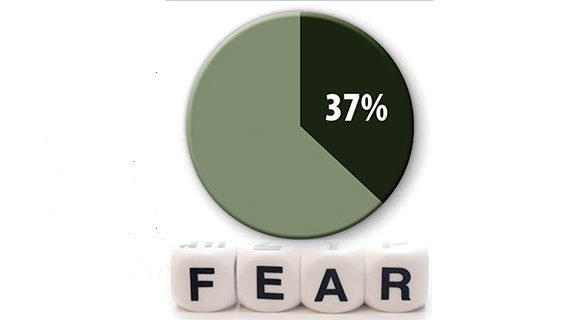

Choking when you’re expected to perform—whether you’re squaring off in tennis or vying for resources or key accounts or a desirable role at work—is actually surprisingly common. It happens with some regularity to probably around one-fifth of the population. Since this response is at least partly hardwired, it’s not something you tend to outgrow as you mature and gain perspective. Thirty years after that match with Paul, I still struggle with it. A lot.

Who chokes and why?

People who choke can be peak performers in some settings, trembling mice in others. The list of elite athletes who have choked spectacularly is extensive. Greg Norman, the Australian golfer, became completely unglued at the 1996 Masters, nervously frittering away a seemingly insurmountable lead over the final few holes. Jana Novotná, the Czech tennis star, was five points away from winning Wimbledon in 1993 when she disintegrated under pressure and blew a huge lead over Steffi Graf. And then there’s Roberto Duran, who famously lost his world welterweight championship to Sugar Ray Leonard. With sixteen seconds left in the eighth round—and millions of dollars on the line—Duran turned to the referee, raised his hands in surrender, and pleaded, “No más, no más (No more, no more).” Until that moment, Duran appeared to be invincible. Since then, he’s been widely considered one of the greatest quitters and cowards in sports history.

That may sound harsh, but just about the worst epithet one can sling at an athlete—worse, in some ways, than “cheater”—is “choker.” To choke is to wilt under pressure, to fail to perform at the moment of greatest importance. A technical definition, as laid out by Sian Beilock, a University of Chicago cognitive psychologist who specializes in the topic, is “worse performance than expected given what a performer is capable of doing and what this performer has done in the past.”

In any performance arena, from sports to the military to the workplace, choking is produced by anxiety and, ipso facto, viewed as an absence of fortitude, a sign of weakness.

Of course, it’s not that simple.

Research shows a strong correlation between your genetically conferred physiology and how likely you are to crack under stress. For instance, a person’s allotment of neuropeptide Y (NPY), a neurotransmitter in the brain that regulates stress responses, among other things, is relatively fixed from birth, more a function of heredity than of learning. People high in NPY tend to be unusually psychologically resilient and resistant to breaking down in high-pressure situations.

But that said, there’s also an element of “nurture” at work here. Psychological resilience is a trait that can be taught; the Pentagon is spending millions trying to figure out how to do that better. It’s possible that those who thrive under pressure have learned to be resilient—that their high levels of NPY are the product of their training or their upbringing.

According to the explicit monitoring theory of choking, derived from recent findings in cognitive psychology and neuroscience, performance falters when you concentrate too much attention on it. This runs counter to all the standard bromides about how the quality of your performance is tied to the intensity of your focus. But what seems to matter is the type of focus you have. As Beilock puts it, actively worrying about screwing up makes you more likely to screw up.

To achieve optimal performance—what some psychologists call flow—parts of your brain should be on automatic pilot, not actively thinking about (or “explicitly monitoring”) what you are doing. Beilock has found that she can dramatically improve athletes’ performance, at least in experiments, by getting them to focus on something other than the mechanics of their stroke or swing. Having them recite a poem or sing a song in their heads, distracting their conscious attention from the physical task, can rapidly improve performance. Chronic chokers—especially those who are clinically anxious—are too distracted from the task at hand by a relentless interior monologue of self-doubt: Am I doing this right? Do I look stupid? What if I make a fool of myself? Can people see me trembling? Can they hear my voice quavering? Am I going to lose my job?

When you look at brain scans of athletes pre- or midchoke, says sports psychologist Bradley Hatfield, you see a neural “traffic jam” of worry and self-monitoring. Brain scans of nonchokers, however—the Tom Bradys and Peyton Mannings of the world, who exude grace under pressure—reveal neural activity that is “efficient and streamlined,” using only those parts of the brain relevant to strong performance.

Does that mean those of us whose bodies are set to quiver in response to the mildest perturbances are doomed to choke any time the pressure is on? Not necessarily. Because when you begin to untangle the relationship between anxiety and performance, it turns out to be very complex. It’s possible to be simultaneously anxious and effective.

Take, for example, Bill Russell, a Hall of Fame basketball player who won eleven championships with the Boston Celtics (the most by anyone in any major American sport, ever). He was selected to the NBA All-Star team twelve times and was voted the league’s most valuable player five times. He is generally acknowledged to be the greatest defender and all-around winner of his era, if not of all time. No one would question Russell’s toughness or his championship qualities or his courage. And yet, according to one tabulation, he vomited from anxiety before 1,128 of his games between 1956 and 1969. His teammate John Havlicek told the writer George Plimpton in 1968, “It’s a welcome sound, too, because it means he’s keyed up for the game and around the locker room we grin and say, ‘Man, we’re going to be all right tonight.’”

Like someone with an anxiety disorder, Russell had to contend with nerves that wreaked havoc with his stomach. But a crucial difference between Russell and the typical anxiety patient (aside, of course, from Russell’s preternatural athleticism) was the positive correlation between his anxiety and his performance. When Russell stopped throwing up for a stretch at the end of the 1963 season, he suffered through one of the worst slumps of his career. For him, a nervous stomach correlated with effective, even enhanced, performance.

How much anxiety is too much?

At some level, it’s normal—adaptive even—to be anxious in our post-industrial era of pervasive uncertainty, where social and economic structures are undergoing continuous disruption and professional roles are constantly changing. According to Charles Darwin (who himself suffered from crippling agoraphobia), species that “fear rightly” increase their chances of survival. We anxious people are less likely to remove ourselves from the gene pool by, say, becoming fighter pilots.

An influential study conducted a hundred years ago by two Harvard psychologists, Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson, demonstrated that moderate levels of anxiety improve performance in humans and animals: too much anxiety, obviously, impairs performance, but so does too little. Their findings have been experimentally demonstrated in both animals and humans many times since then.

“Without anxiety, little would be accomplished,” David Barlow, founder of the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University, has written. “The performance of athletes, entertainers, executives, artisans, and students would suffer; creativity would diminish; crops might not be planted. And we would all achieve that idyllic state long sought after in our fast-paced society of whiling away our lives under a shade tree. This would be as deadly for the species as nuclear war.”

So how do you find the right balance? How do you get yourself into the performance zone where anxiety is beneficial? That’s a really tough question. For me, years of medication and intensive therapy have (sometimes, somewhat) taken the physical edge off my nerves so I could focus on trying to do well, not on removing myself from the center of attention as quickly as possible.

For those who choke during presentations to board members or pitches to clients, for example, but probably aren’t what you’d call clinically anxious, the best approach may be one akin to what Beilock has athletes do in her experiments: redirecting your mind, in the moment, to something other than how you’re comporting yourself, so you can allow the skills and knowhow you’ve worked so hard to acquire to automatically kick into gear and carry you through.

Your focus should not be on worrying about outcomes or consequences or on how you’re being perceived but simply on the task at hand. Prepare thoroughly (but not too obsessively) in advance; then stay in the moment. If you’re feeling anxious, breathe from your diaphragm in order to keep your sympathetic nervous system from revving up too much. And remember that it can be good to be keyed up: the right amount of nervousness will enhance your performance.

Author: Scott Stossel, adapted from his book, Age of Anxiety