The Opportunity Zone program has faced criticism for benefiting wealthy investors who are planning projects in neighborhoods not considered distressed, and will instead provide a large return on investment.

In Baltimore, officials there were found to have redrawn an Opportunity Zone to include a development led by Under Armour chief executive Kevin Plank, who had lobbied state officials for the change.

In Chicago, a similar situation emerged after an area that did not meet city guidelines for an Opportunity Zone was later added to include a $2 billion project to redevelop a former hospital, after state officials intervened.

And in New York, Amazon was eligible to offset millions of dollars of capital gains taxes in its failed bid to open a headquarters in Long Island City, where much of the high-rise neighborhood is an Opportunity Zone.

Sec. Ben Carson is touring the country to promote OZs, and recently announced updates to the program’s rules.

Developers who redevelop mixed-use buildings in Opportunity Zones will now be eligible to receive Section 220 mortgage insurance for projects that derive up to 30 percent of gross income from commercial space. Previously, that had been limited to 15 percent.

The Federal Housing Administration is also expected to unveil a new set of incentives for Opportunity Zones, which will lower mortgage and application fees for loans the agency issues.

When the tax incentives behind the Opportunity Zone legislation came out as part of the JOBS Act in 2017, it seemed like the program was poised to create investment into historically downtrodden areas around the country. But, while tax-free capital gains income is nice, it seems that it might not be enough to overcome what many investors see as risky bets.

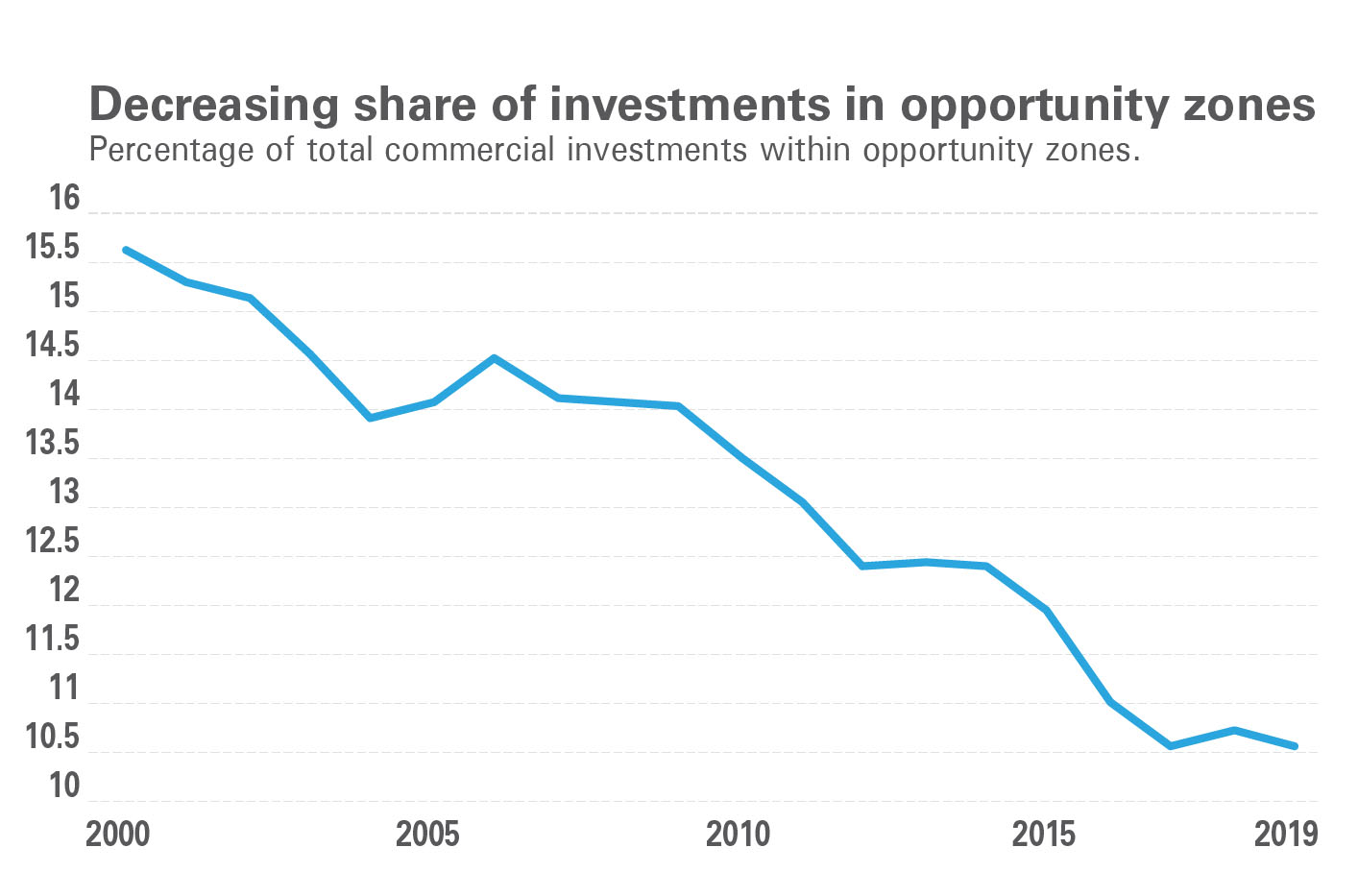

A study came out recently from commercial real estate data platform Reonomy that shows how little the Opportunity Zone legislation has done for most areas that received the designation—at least so far. It shows that in 2019, only 10.7 percent of all commercial real estate transactions in the U.S. were in Opportunity Zones, down from 15.5 percent in 2000.

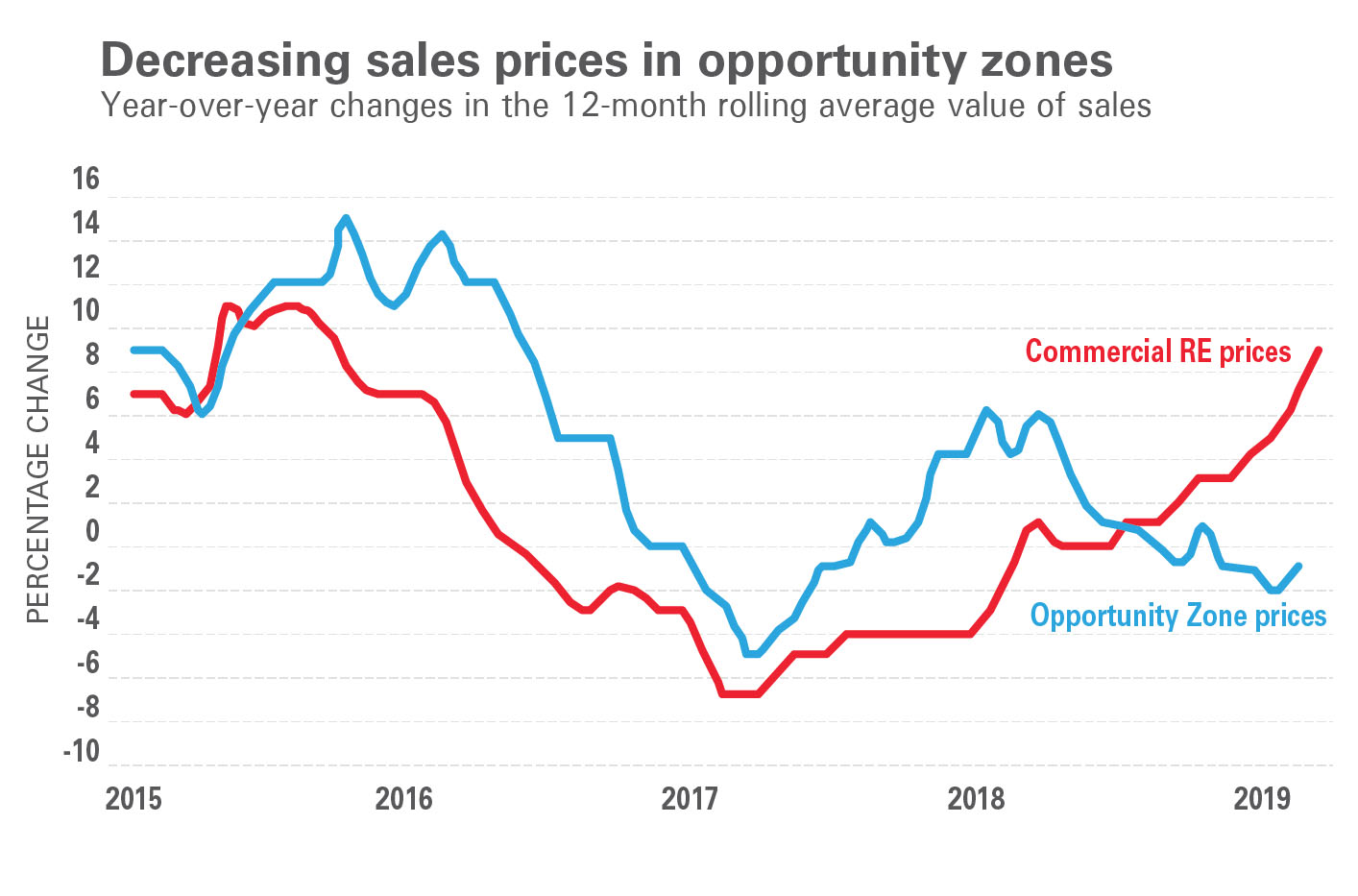

Because of the slowdown in sales, Opportunity Zones properties are actually seeing a price decrease. In chart 1 we see that the prices in Opportunity Zones have fallen while the rest of the commercial property stock has been on the rise:

What could be the cause for this counterintuitive slowdown in Opportunity Zone transactions? Sam Viskovich, VP of marketing at Reonomy has a few ideas, “Until recently, legislation on Opportunity Zones wasn’t finalized, which was impeding clarity for many markets. Layer on strict regulations on how investments have to be made via Qualified Opportunity Funds, and that might be causing a large barrier to entry for a lot of players.”

It might not just be the red tape keeping investors away. Viskovich added, “The last twenty years of data show that these areas definitely needed the attention OZ legislation intends to spark, but long term, that downward trend might be difficult to reverse. Despite incentives, the wider economic trend shows that lower socio-economic areas are failing to attract their share. Numbers also show investors and developers have stayed in relatively safer tracts and I think they might continue avoiding risky endeavors.”

This has also been the observation of the consulting firm Webster Pacific. They did a study in May that examined wealth growth in each of the zones. What they found was that the biggest gains were made by Opportunity Zones that were already much higher up on the economic spectrum. Here is an excerpt from an article that I previously wrote about the report:

“What Webster Pacific found was that some of the top 50 Opportunity Zones were already wealthy and got much wealthier; the most extreme examples include tracts in New York, Houston, San Juan (P.R.), and Silicon Valley. The single leading metropolitan area is New York City, which contains nearly four times as many high-growth tracts as the next highest area, the San Francisco Bay Area. Also, none of the top 50 were in the South or in New England and very few were in the Midwest.” I talked to Larry Kosmont, head of Kosmont Companies, a real estate and economic development advisory about this trend. He agreed that lack of clarity was keeping many investors from jumping into these areas, “Despite all the promotional bluster, there is limited activity on new OZ deals because there are still too many essential investor compliance questions that temper the appetite for entering into Opportunity Zone deals. I expect this reluctance will dissipate when we get through this next round of clarifications.”

He added that there are also some effects from the slow explanation of the rules. The investments have hold periods for tax deferrals, which increase the longer an investment is held. Those timelines, in some cases, have not started, even though the capital has been tied up because of ambiguity in what constitutes “significant improvement.”

One of the reasons Larry thinks that the prices have dropped for properties in the Opportunity Zones is that the prices got inflated by investors who expected, as many of us did, for the Act to be a gold rush. But he does see a price floor ahead, adding that “I think the initial irrational price exuberance is starting to normalize.”

There certainly seems to be enough money flowing into the space. A JLL study estimates there to be 138 large CRE funds targeting Opportunity Zones that have a total of more than $44 billion in equity. Of this money “most of it” is invested in funds with investment mandates. These mandates require that a certain amount of the investment pool is put into a specific property type. This is where the report said that those mandates required investment to be directed: “82 percent of capital in multifamily, 60 percent for office and 49 percent for retail. Industrial opportunities are thus far under-appreciated.”

Anyone who has ever been caught in “the bad part of town” knows that they are usually mostly industrial areas with very few large apartment buildings that would appeal to the typical multifamily investor. It is exactly these “bad” parts of town that could use the most help from the investment and development communities. While these mandates have probably been created under the best intentions, they might be experiencing the unforeseen consequence of self-selecting areas that are already a few rungs up the urban renewal ladder.

The mission behind the Opportunity Zone tax breaks is noble. Pushing money to rebuild areas that don’t normally get a lot of investment could be a great way to breathe new life into our poorest communities.

Gentrification might have recently taken on a negative connotation for some, as it can often displace the most vulnerable, but a study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and NORC at the University of Chicago has found that there are actually positive benefits to original residents of gentrified neighborhoods. But noble causes are one thing and creating meaningful change is another. So far it seems like the rules that surround the Opportunity Zones’ incentives are too vague and too stringent for many investors. Plus, investors realize that not all of these zones are created equal so they cherry pick the ones that are the most similar to the investments in which they are familiar.

In the end, it might take a lot more to get investors to make bets on areas with low growth potential that would get enough money flowing into poor areas to help bring the residents out of poverty.

Author: Franco Faraudo has worked in real estate as an agent, manager, and investor. He writes about the intersection between the physical and digital world and is a co-founder of Propmodo.