Until a decade ago, only a handful of companies specialized in redeveloping environmentally blighted land, and mostly for commercial and industrial product because of the higher clean-up standards for residential use. Even then, it was a risky proposition.

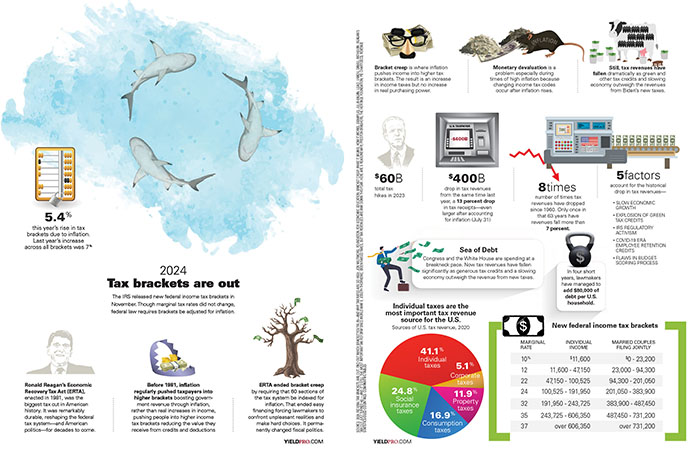

“The statute of the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response Compensation and Liabilities Act (CERCLA) painted the big picture,” explains Ken Gray, Esq., a partner at Pierce Atwood’s Portland, Me., office. Gray spent a number of years during his 27-year environmental law practice advising the EPA in Washington, D.C. “Until CERCLA was amended in 2002, the only meaningful defense for a developer was the innocent landowner defense. It meant you did your due diligence, as defined by the ASTM E1527-05 phase one environmental site assessment process, and if you found there were hazardous substances, or likely to be hazardous substances on the property, you did not qualify for that defense and you purchased the property at your peril.

“The 2002 amendments added a new defense, called the Bona Fide Prospective Purchaser (BFPP). That defense said you can now own contaminated property without having the additional liability for that contamination, as long as you also met certain conditions enumerated in the statute, the first of which was you had to do all appropriate inquiry for the BFPP. Along with amending the Superfund law to add a new defense in 2002, Congress also assigned the EPA the task of defining all appropriate inquiry, which it did through rule making. The rule was adopted final in November 2005 and effective a year later,” Gray explained.

The EPA’s final rule on all appropriate inquiry was the defining piece of the protection puzzle that sold Trammell Crow Residential (TCR) Southwest Managing Director Jeff Allen on building apartments on brownfields near urban centers, where develop-able greenfield sites are almost impossible to find.

Allen discovered the final rule about the time the document was published. He was under due diligence on a 19.4-acre brownfield TCR had optioned in April 2005 for development of Alexan MetroPointe, a 408-unit, garden-style community. The site is within one of Tempe’s principal employment nodes, close to the I-10 and about five miles north of Downtown Phoenix.

The site had been owned by Sanders Aviation, a crop dusting company that legally used chemicals such as toxophene for cotton (one of the four C’s of Arizona industry that also include copper, cattle and citrus) from 1951 until the substance was banned by the state in the 1980s. The Sanders family spent approximately $1.1 million on site clean-up before selling the land to a speculator group that planned to down-zone it to light industrial use. The EPA, which in 1994 excavated 25,500 tons of soil to a depth of six feet and back-filled, also determined the site inappropriate for residential development and placed deed restrictions on the land.

But the market changed in favor of multifamily, and the parcel became more valuable to multifamily developers. After a final phase of remediation ” conducted by environmental engineers and consultants Brown and Caldwell, which excavated another 20 tons of near-surface soil ” the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality (ADEQ) confirmed late last year that 18.4 acres of the site were suitable for unrestricted residential use. The remaining acreage also was deemed suitable, if intrusion of the soil six feet below the surface was controlled.

When Allen learned about the EPA’s final rule, he contacted his environmental council and environmental engineers. “I said, ‘Gee, it looks to me like we’ve just gotten the blueprint for mitigation of this site and for protecting everyone going forward. All we have to do is follow the blueprint.’ The response from the environmental engineers, who certainly were more up to date with this than I was, said, ‘That’s exactly correct, you just have to spend a little more money to follow their standard,'” said Allen.

Although the rule wasn’t yet a requirement, it gave TCR clear guidelines to promote the project to investors and get through the permitting process. The company opted to follow those guidelines to the letter. Allen notes TCR would have pursued the project on a direct investment basis using Crow Holdings, which owns and directs the investments of the Trammell Crow family and its investment partners, if another investor hadn’t stepped up.

Boston Capital came aboard as equity partner in June. AmSouth Bank provided land financing, which will convert to construction financing upon TCR’s receipt of the approval of final construction drawings.

TCR is spending an additional $10,000 to develop project-specific guidelines that are being handed out to all parties to the development, including subcontractors, TCR’s own in-house general contractor and the management team, to ensure compliance with the rule post completion. “That’s true for all the utility lines that run through the site that will be dedicated to the municipality,” said Allen. “The municipality has to know what they can and can’t do within these impacted areas.”

No structures will be built at two locations that will remain open space or paved over. “We were required to include 40 percent open space ” a total of 9.83 acres. We achieved 50 percent,” says Allen. This was necessary because the city requires all onsite flows be retained there. “We had a gas pipeline easement 60 feet wide that runs through the property and we ended up with large view corridors. We’re elevating the grade as a condition of the topography, bringing in soil to increase the height of the site, which was necessary just for drainage purposes, but does create additional room for error,” says Allen.

Even though studies showed the contaminants were contained within the top six feet of soil and anything below six feet could be developed, TCR gerrymandered the buildings and improvements around those areas, minimizing the potential for intrusion.

Within the last 70 days, the state raised another hurdle when it released a proposed revision of the soil remediation standards rules required for soil contamination, which not surprisingly include pesticides like toxophene. TCR will meet those as well.

Alexan MetroPointe, designed as a mix of 228 one bedrooms, 144 twos and 36 threes by Todd & Associates, will break ground in January and open about nine or ten months later. Allen expects absorption to average 25 to 30 units per month with stabilization at 95 percent occupancy in around 13 months, after which TCR plans to market the community for sale.

Allen believes TCR will be the first in Arizona, and maybe the country, to come out with a site designed and developed pursuant to the final EPA ruling. His experience with Alexan MetroPoint has left him bullish on brownfields. “I’ve talked with a few people who make a market in that business and encouraged them to bring those deals to me. If it’s priced appropriately to compensate for the time and effort, I don’t see why we wouldn’t pursue properties with similar problems.”

Because Metro Phoenix has become a hot market for commercial and industrial, the most likely candidates for brownfields, there is competition from those sectors today. But Allen sees a silver lining in the slowdown in the single-family home arena. “The publicly traded single-family homebuilders aren’t brow-beating the apartment players at the offering table when they are trying to buy land more appropriate for multifamily but that the single-family guys were buying just to keep the engine running.”

When Alexan MetroPointe comes online, the community will compete with a number of high-density, transit-oriented apartment projects inspired by the light-rail that runs through Tempe. Although Allen considers both brownfield and TOD (transit oriented development), he points to one unfortunate aspect of high-density housing. “The construction required for high-density moves out of wood frame into steel and concrete, commodities that have increased astronomically in price,” says Allen. “You have to build structured parking to get the higher densities and the materials and labor costs are prohibitive, especially with the resurgence in commercial development.”

Construction hard costs are somewhere in the neighborhood of 70 percent to 80 percent of a project’s total cost. For Alexan MetroPointe they are running in the $70 per square foot range. Allen believes if you can reasonably predict those costs going in, the added cost of mitigating a brownfield is one of time and minimal additional technical studies and compliance on a post-completion basis. “All else being equal, I would do three to four brownfield developments versus a higher density project that would take longer to deliver with higher costs.”

Others may be encouraged to do the same. “The BFPP gives a green light to developers,” says Ken Gray, who believes the Bona Fide Prospective Purchaser defense under the new rule provides another safe harbor and creates a whole new class of landowners who have the ability to recover their cleanup costs from parties who caused the problem.

That green light may widen the playing field for multifamily developers, but predevelopment specialists, who have dominated the niche, may find their pipelines shrinking.

“It certainly limits my business,” said Seth Weinstein, CEO of Hannah Real Estate Investors LLC, a specialist in complex brownfield, historic and waterfront development for a number of years. A portion of the company’s business includes predevelopment work for apartment and other developers unwilling to navigate the environmental risk.

“Since the mid-80s, I’ve been willing to take on, where appropriate, environmental and entitlement risk and position property where companies such as an AvalonBay or TCR ” although I’ve never done work for TCR ” could get a clean, entitled property and move ahead to do the types of developments they had in mind. By taking some of that risk off the table and giving these companies more comfort to take on the environmental risk themselves, it limits a substantial wing of my predevelopment business.”

Weinstein uses, as an analogy, the early 1980s when asbestos was considered to be a voodoo-esque type of risk. Because he viewed the process as a cost factor and knew how to remediate the hazard and the costs involved, Weinstein would acquire buildings with asbestos at a discount substantially larger than the cost of remediation and complete the work. “As asbestos became seen as less of a serious risk from the office building community, there were more players willing to take on that environmental task and it became less of a barrier to entry,” said Weinstein. “The same is true today with brownfields now that the government has made it somewhat safer for more players to enter the game. It’s lowered the barrier to entry.”

Also reducing barriers to entry is the evolution of environmental insurance, which is becoming more and more available to developers who are able to insure their risk in ways they couldn’t before. “The all appropriate inquiry change makes it more attractive to the insurance company and reduces the risk to the insurer so the insurance product becomes more protective and a bit cheaper,” Weinstein explains. “At one point, AIG provided the only reasonable product. Now there is a multiplicity of environmental insurers and more sweeping coverage at much lower prices.”

More developers may step up to take on environmental challenges themselves rather than work through predevelopment agencies, but Hannah’s soup-to-nuts development business is the same as it ever was. The company has six projects under construction in Connecticut, all mixed-use with a residential component. Three involve substantial brownfield effect.

“We have about $350 million under construction now and probably will do a couple hundred million dollars more in the next couple of years. We’re targeting a billion dollars of business during this decade and expect we’ll have enough to keep us busy,” said Weinstein.

Projects include the recently sold-out, 92-unit Mill River House condos, which the company built after mitigating the site of a former car dealership, repair facility and gas station. The 60-unit Adams Mill River House across the street is 70 percent pre-sold. Sales are almost complete at Stonington Commons in Stoning-ton, which consists of 34 high-end condos and seven single-family homes on the site of the oldest extant factory in New England that dates back to the pre-revolutionary war period. Just getting started is a mixed-use project on about five acres in Fairfield. Glen View House in Stamford, a 146- unit luxury apartment project with a Walgreens drugstore on the ground floor, is rising at the site of a former Cadillac dealership. The project is scheduled for completion in 2008. Expect Weinstein to do more rental projects going forward.

With years of experience and the ability to make quick decisions, Hannah Real Estate Investors has an edge on the competition. “We know pretty much when we go on a site what’s going to be there based on its history and we’re willing to take a little higher risk profile because we know what we’re doing. We have a substantial track record and it does give us an advantage in acquiring property. But our real advantage in acquiring property is our track record on closure. I’ve never started a negotiation on a piece in a serious way that I haven’t closed on,” said Weinstein.