But several developments unfolding right now could make the next five or six months among the more consequential periods for housing-finance policy since the companies were taken over by the government five years ago. Here are three reasons why:

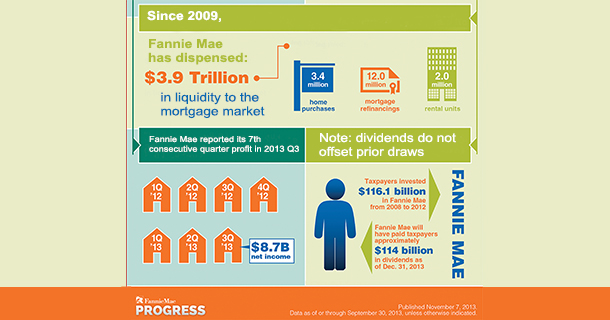

First, Fannie and Freddie are now reporting large profits. This could make it easier for the company’s defenders–who were silent when the firms were hemorrhaging cash during the bust–to more forcefully lobby in favor of less dramatic changes. By next February, when both companies report their fourth quarter earnings, both firms should be able to say that they’ve sent more in dividends to the U.S. Treasury than the amounts they were forced to borrow over the previous five years.

Rising profits could also trigger an important but obscure change in federal budgeting, where congressional accountants “score” the firms as revenue-generating entities. If that happens, Congress would either have to raise revenue or cut spending elsewhere as part of any overhaul.

Second, the Obama administration is moving ahead with plans to install a permanent director to the independent agency that oversees Fannie and Freddie, the Federal Housing Finance Agency. The director of the FHFA is an incredibly powerful job because it can stand in the shoes of the shareholders and board of directors of both companies, plotting long-term strategy and making day-to-day management decisions.

President Obama’s nominee for the job, Rep. Mel Watt (D., N.C.), failed to win enough votes to overcome a procedural hurdle for his confirmation vote last month. The White House appears to be focused for now on getting Watt confirmed this year, dislodging Edward DeMarco, the agency’s acting director. With Congress at least a year–and possibly several more–from getting a bill to the president’s desk, the FHFA director will have considerable sway shaping the transition process.

DeMarco has stoked some concerns within the housing industry over his decision to wind down the companies footprint in single-family and multifamily lending. Current and former administration officials in recent weeks have suggested that Watt might bring a more transparent and deliberate approach to such transitional steps.

Third, the Senate Banking Committee is working in a bipartisan fashion toward constructing a comprehensive housing-finance overhaul bill that will address the future of Fannie and Freddie. They’re building on the work of Sens. Bob Corker (R., Tenn.) and Mark Warner (D., Va.), who have introduced a bill with support from five other Republicans and four other Democrats. The heads of the committee, Sens. Tim Johnson (D., S.D.), and Mike Crapo (R., Idaho), have made clear that they hope to reach agreement on a bill this year.

Bipartisan agreement is far from assured. It involves threading a needle between three general groups: the centrist supporters of the Corker-Warner bill, liberal Democrats who want to see a larger government role (particularly in affordable housing), and conservative Republicans who are wary of continued, heavy federal involvement in the mortgage market.

Whatever the committee produces will essentially mark the starting point for what, if anything, Congress is able to pass in 2015 or 2017. In other words, even if this is only the first inning, a number of key decisions could get made here that define the boundaries for the rest of the game.

House Republicans have advanced their own bill with no Democratic support, which should serve as one end point for any overhaul. How far more-conservative House Republicans are willing to bend to support a greater federal role in housing could determine how soon a bill arrives on the president’s desk.

Lawmakers further out on the left, meanwhile, are likely to insist that this new system provides sufficient credit access to low- and moderate-income households. They’re wary of any market in which government guarantees mostly serve the borrowers that arguably need them the least. Among the key questions to unfold: what does the White House do if liberals decide that the centrist Senate bill doesn’t go far enough?

The next few months could show whether there’s any reasonable chance of getting legislation passed while Obama is in office, or whether these decisions will get kicked down the road beyond 2017.

Author: Nick Timiraos, wsj.com