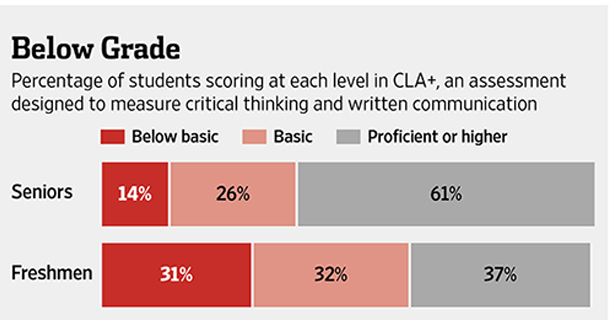

Four in 10 U.S. college students graduate without the complex reasoning skills to manage white-collar work, according to the results of a test of nearly 32,000 students.

The test, which was administered at 169 colleges and universities in 2013 and 2014 and released Thursday, reveals broad variation in the intellectual development of the nation’s students depending on the type and even location of the school they attend.

On average, students make strides in their ability to reason, but because so many start at such a deficit, many still graduate without the ability to read a scatterplot, construct a cohesive argument or identify a logical fallacy.

“Even if there is notable growth over four years, many students are starting at such a low point they may still not be proficient at the point of graduation,” said Jessalynn K. James, a program manager at the Council for Aid to Education, which administered the test. The CAE is a New York-based nonprofit that once was part of Rand Corp.

The exam, known as the Collegiate Learning Assessment Plus, measures the intellectual gains made between freshman and senior year. The test doesn’t cover subject-area knowledge; rather it assesses things like critical thinking, analytical reasoning, document literacy, writing and communication—essentially mimicking the baseline demands for professionals.

“These are the skills that are important no matter what you are doing; if you’re serving on a jury or looking for a good candidate to vote for, these are highly transferable skills,” James said.

The test comes at a time of rising tuition and student debt and a broad rethinking of the value of a college degree in a changing job market. In December, President Barack Obama spelled out plans for a college-rating system that aims to assess how well schools prepare students for the work world, among other criteria.

The 40 percent of students tested who didn’t meet a standard deemed “proficient” were unable to distinguish the quality of evidence in building an argument or express the appropriate level of conviction in their conclusion.

The results are “consistent with our work,” said Richard Arum, co-author of “Academically Adrift” and “Aspiring Adults Adrift,” which chronicles the paucity of studying and intellectual development on college campuses and the consequences after graduation.

“Colleges are increasing their attention to the social aspects on campus to keep students happy; there is not enough rigorous academic instruction,” he said.

A survey of business owners to be released in January by the American Association Colleges and Universities also found that nine out of 10 employers judge recent college graduates as poorly prepared for the work force in such areas as critical thinking, communication and problem solving.

“Employers are saying I don’t care about all the knowledge you learned because it’s going to be out of date two minutes after you graduate… I care about whether you can continue to learn over time and solve complex problems,” said Debra Humphreys, vice president for policy and public engagement at AAC&U, which represents more than 1,300 schools.

The CLA+ is graded on a scale of 400 to 1600. In the fall of 2013, freshmen averaged a score of 1039, and graduating seniors averaged 1128, a gain of 89 points.

CAE says that improvement is evidence of the worth of a degree. “Colleges and universities are contributing considerably to the development of key skills that can make graduates stand out in a competitive labor market,” the report said.

Arum was skeptical of the advantages accrued. Because the test was administered over one academic year, it was taken by two groups of people. A total of 18,178 freshmen took the test and 13,474 seniors. That mismatch suggested a selection bias to Arum.

“Who knows how many dropped out? They were probably the weaker students,” he said.

James said first-year students expect to sit for a battery of tests when they arrive at college, but seniors had little incentive to take the exam. The CAE attempted to statistically correct for the selection bias, but because the test wasn’t administered to a single group over four years, there were inherent limitations.

“It’s accurate to the extent possible,” she said.

The results revealed that the greatest cognitive growth occurred at midsize schools—between 3,000 and 10,000 students—in the Western part of the country. Students who made the most significant gains were likely to be minorities and low-income students, but their scores were also lower on average to start.

What are schools in the West doing better than everybody else?

“We don’t know,” said James. “We’re going to look at the curriculum, but it may be the cultural aspect of the student experience.”

Author: Doug Belkin covers higher education and national news out of the Chicago bureau of The Wall Street Journal.