In November 2018, election ballots in California might include a question on rent control. Right now, California law restricts the spread of rent regulations on housing built after 1995, in addition to many older properties.

Some housing advocates want to change that. A proposed law that would have allowed more rent regulation died in the state legislature in 2017. Now advocates including the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment and the San Francisco Tenants Union are pressing the same proposal as a ballot initiative.

If these advocates succeed, some local governments would probably expand their rent control laws. It would mark one of the first expansions in decades of the housing units covered by rent regulation, though some cities and towns have created other kinds of regulations to protect renter households in gentrifying neighborhoods as apartment rents grow faster than incomes on average nationwide.

The apartment industry is taking notice. “If you are an owner of apartments, rents controls are a very, very scary thing,” says John Sebree, director of the national multihousing group for brokerage firm Marcus & Millichap.

Rules restrict rent regulation

In most parts of the U.S., lawmakers are simply not allowed to create new rules to limit by how much landlords can raise rents at their properties. If local officials want to create more housing for lower-income renters, they have to make deals one at a time with individual property owners, often using affordable housing programs to trade tax breaks or zoning changes for legally-binding promises to keep rents low.

Only five states in the U.S. currently have jurisdictions that have rent regulation or rent control laws on the books: California, Maryland, New York, New Jersey and Washington, D.C.

Even in these states, rent regulation typically does not extend to the rents on new apartment units. In California, the Costa Hawkins law keeps rent controls away from housing built after 1995, in addition to many older properties. In New York, rent stabilization law only applies to housing built before 1974. New York apartments escape rent regulation once their rents rise above $2,700 a month and they become vacant. As a result, the total number of rent-controlled apartments is steadily shrinking.

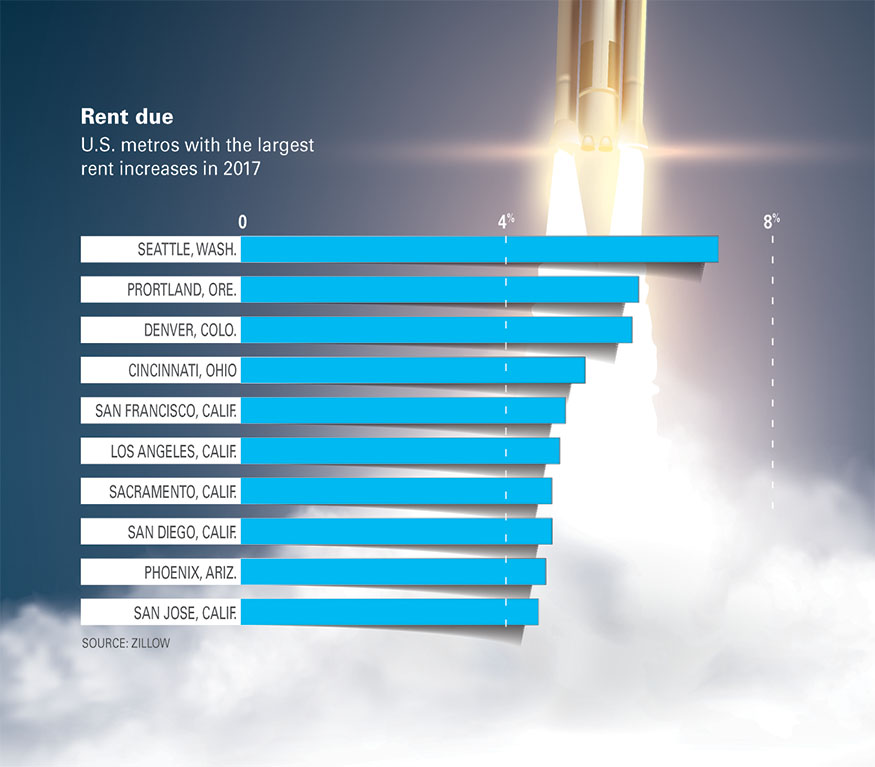

Another seven states don’t have laws that prohibit rent regulation or rent control, so towns and counties in these states could potentially create new rent laws. Those states include Alaska, Maine, Montana, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia. However, these states are generally not the places where rent regulation is most often proposed and debated. The exception that proves the rule might be Portland, Maine, where advocates recently got a measure onto the ballot to allow rent regulation, in response to rapidly rising housing costs in that city. The ballot measure was defeated.

Throughout the rest of the country, including more than two-thirds of the states, state law makes it impossible for local governments to create rent regulations that broadly restrict the ability of landlords to set their rental rates as high as the market will support. In some of these states, advocates for rent control propose changing the law. Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan and Oregon have all had seen recent efforts to remove their prohibition against rent control laws.

Laws to stop displacement

Multifamily developers often argue that rent regulation that extends to new construction would reduce the incentive to build new housing. In the long run, a smaller number of rental units would increase the competition for housing, forcing rents higher overall.

“If there is a negative effect on housing supply, you’re not really moving the affordable housing discussion ahead,” says Rebekah King, acting director of policy for the National Housing Conference (NHC), a non-profit organization focused on affordable housing.

However, local officials have found other options to protect tenants without using rent regulation. In Portland, Ore., a recent law forces landlords to pay the relocation costs for residents who are forced to move by rents that increase 10 percent or more in a year. Those relocation costs can add up to more than $3,000 per household, according to NHC.

Also, in New York City, a whole series of new laws protect renters from eviction. The city now provides lawyers to tenants threatened with eviction. Renters who live in rent-stabilized apartments are also protected from harassment by property owners eager to drive them out of their units. These laws don’t create new rent-stabilized apartments, but help keep the number of rent-stabilized apartments from shrinking as quickly as it might otherwise.

Author: Bendix Anderson