While the UltraFICO would certainly expand financial inclusion, consumers must be wary of inscrutable offers of credit, and learn how exactly they could protect their data.

Essentially, the UltraFICO score is calculated using people’s bank transaction data, by studying their financial behavior through the activity in their checking, savings and money market accounts. Fair Isaac Corp. is partnering with credit bureau Experian and data aggregation firm Finicity of Murray, Utah, to launch the new offering.

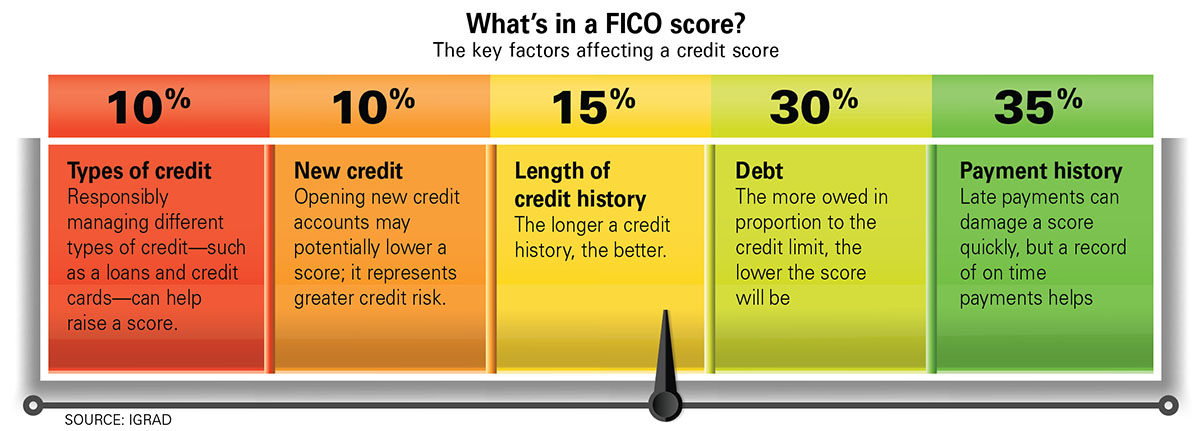

“The name of the game here is a more accurate prediction of risk,” said Wharton real estate professor Benjamin Keys, who is also a faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research. The UltraFICO score also would consider aspects of a consumer’s financial behavior previously tracked, such as how long they have had credit cards and their payment history.

“They can take some people who previously didn’t look like they were very creditworthy from the perspective of a lender, and thanks to this additional information, shift them into the other category,” Keys said. The UltraFICO Score is essentially trying to pull in more people who have “a thin credit-file problem,” or who don’t have much of a credit history, he noted. In theory, the new score provides a well-rounded view of a consumer’s creditworthiness—their credit history, income and their assets.

“People who may be overdrawing their checking accounts or have very minimal or spotty savings records with their savings accounts could potentially be negatively affected by this scoring model,” said Christopher Peterson, law professor at the University of Utah’s Quinney College of Law. He was formerly a special advisor in the Office of the Director at the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Although the UltraFICO Score is being promoted as “this wonderful new thing, it’s complicated,” he added. “For some people, this is going to make it clearer that they’re not creditworthy. I also think that there are some concerns about privacy and the potential for emboldening some risky forms of higher-cost lending.”

Pressure from lenders

FICO as a company was driven to launch the UltraFICO score because of two factors, according to Keys. One is pressure from the lending industry to “expand the credit box,” especially when the median FICO score to qualify for a housing mortgage loan has risen from about 700 in 2000-2001 to about 750 currently, he said. “The pendulum of lending, especially in the mortgage space, has swung from being extremely loose in the mid-2000s to being quite tight.”

The second factor is competition from the credit reporting bureaus, who have been actively promoting their VantageScore product with lenders, Keys said. He added that there has been a move to expand credit also because delinquencies have fallen across most types of credit, barring student loans and subprime auto loans.

“The dream here for lenders is they want to increase lending without taking on more risk,” Keys said. “The idea that you can simply boost lending without taking on more risk is very unlikely.” He wondered how valuable the new information that FICO plans to collect will be in terms of its “predictive power.”

Below the radar

According to FICO, the UltraFICO score would “attract the underbanked—the self-employed, millennials, immigrant entrepreneur, migrant savers and remitters.” It would also expand the lending base by bringing greater visibility to consumers’ credit information, and give consumers who may have suffered financial distress a second chance, the company said. “It is among the biggest shifts for credit reporting and the FICO scoring system, the bedrock of most consumer-lending decisions in the U.S. since the 1990s,” a Wall Street Journal report said.

For sure, the UltraFICO Score could help “a few million people” secure a credit score similar to the traditional FICO score, said Peterson. They would include people who don’t have credit cards or mortgage loans that are conventionally tracked to assess creditworthiness, but do have bank accounts, he added.

At the same time, consumers with low credit scores do have access to credit such as payday loans, although they may be very expensive, said Peterson. “There are still nearly 20,000 payday lenders at storefront locations around the country and a lot of online payday lenders that are providing loans with average interest rates of 400 percent or more,” he added. Some states, such as Pennsylvania, stipulate an interest rate that excludes some of the highest-cost lenders.

While some consumers may look like “desirable credit risks,” others may have used alternative financial services such as payday loans or pawnshops, Peterson said. “Some of the people who are brought into the credit reporting system by this new scoring method will look positive from the perspective of lenders, but some of them are going to look negative,” he cautioned.

“The problem is not just what people’s credit scores are, but whether or not we’re also tolerating loans that are counterproductive for society,” said Peterson. “One of the concerns I have about the UltraFICO Score is how installment lending companies, payday lenders and other alternative financial services providers are going to use this new score to get into the pockets of people who may not be helped that much by higher-cost loans.”

Data and identity theft

Peterson raised concerns over whether the UltraFICO Score would collect more consumer financial data than is desirable. “This is just another way to gather more data about us, including how much money we have in our bank accounts, what our payment patterns are, our spending history, and whether or not we overdraw our checking accounts,” he said. “That’s just more information that’s getting sucked up into the data brokerage industries that sell this information to interested parties.” He also worried about whether the new credit scoring product would heighten risks of identity theft. He noted that hiring decisions could also be impacted by the UltraFICO Score, adding that it is “legal and permissible” for employers to check credit scores before they hire somebody.

Unlike with other markets, consumers have historically not had a say in the types of credit information about them that is collected, Peterson noted. The UltraFICO Score is promoted as one that would seek permission from consumers. “But I’m a little bit skeptical about whether or not consumers will have a robust level of voluntariness here,” he said. “I wonder whether or not this is not something that’s going to get slipped into a form or into boilerplate contracts that people don’t read.”

Individuals have a right to audit their credit scores under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, but Peterson is not sure if that provides the required protections. “Just because you have the right to audit doesn’t mean that you have the time or the background information or the understanding of the system to be able to successfully do that.”

For consumers, the UltraFICO represents another aspect of their financial lives they have to deal with “to manage their financial reputations,” Peterson noted. How will the information be presented? How is consumer access to the data going to be ensured? How will consumers be informed so that they can check and fix potential problems or correct information? These issues aren’t insurmountable, Peterson said, but the UltraFICO “has to be understood in the context of all the other things we’re already supposed to do to keep on top of our finances.”

Keys strongly urged consumers to regularly check their credit scores that are freely available once annually on the Federal Trade Commission’s website, or through the websites of the three credit reporting bureaus—Experian, TransUnion and Equifax. The three bureaus also provide the so-called VantageScore through a joint venture.

Source: Benjamin Keys is Wharton real estate professor and faculty research fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Christopher Peterson is a law professor at the University of Utah’s Quinney College of Law and former special advisor in the Office of the Director at the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.