When it comes to hiring, democratic decisions lead to better outcomes. There is wisdom in crowds when it comes to spotting talent. When Google tracked the performance of recent hires against their interview ratings, the company found that averaging the ratings of a group of interviewers was by far a more accurate predictor of success than the rating of a single interviewer, even if that interviewer was an HR leader or one of the company’s founders.

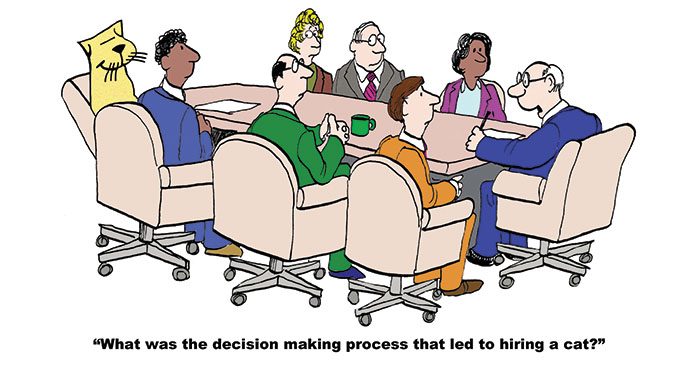

But a hiring-by-committee approach carries its own unique pitfalls. Without careful orchestration, groups can make bad decisions too. Indeed, the dominant approach to hiring today—in which the hiring manager convenes a huddle and goes around the room hearing opinions on each candidate is particularly prone to groupthink. That is because in free-form discussions, the person with the metaphorical “loudest voice” typically over-influences the committee’s decision. This is usually the highest-ranking person; however, it can also be someone who has been established as a “good interviewer.”

But as Google’s data shows, almost no interviewer will consistently get it right more often than a true group decision. Indeed, only one out of the tens of thousands of Google interviewers consistently outperformed group averages—and it’s probable this was just a statistical anomaly, and this “super-interviewer” would have eventually reverted to the mean if Google had continued the study.

Most organizations I speak with believe they are already making group decisions when hiring. When I then observe their process, I notice that while most of their executives are genuinely interested in hearing every interviewer’s opinion, they are missing one critical step and unknowingly falling into a groupthink trap. When individuals do not think long and hard about their own opinions before a free-form group discussion, they are likely to gravitate towards the view that seems most popular; even with a good moderator who promotes psychological safety and dissent, free form discussions reduce the variance of judgments, and this, in turn, suppresses useful discussion that would otherwise occur.

How to make a group decision

In order to make true group decisions about candidates, I advise hiring managers to follow a rigorous process, to ensure that your interviewers maintain a healthy level of independence:

First, make it clear to interviewers that they should not share their interview experiences with each other before the final group huddle. It’s OK for one interviewer to tell the other interviewers that they didn’t have time to cover a certain topic or that they would like the next interviewer to dive deeper into a certain area, but they should make a strong effort to not disclose what their impression of the candidate is by tone of voice or the content of a request.

Next, ask each interviewer to perform a few steps before the group huddle:

- distill their interview rating to a single numerical score.

- write down their main arguments for and against hiring this person and their final conclusion. This will help them stay true to their beliefs once the discussion starts, which leads to less biased predictions.

- If interviewers are emailing in their numerical scores and thoughts on a candidate, don’t include the entire group in the email. In a recent interview, Prof. Shane Frederick at Yale School of Management told me that he actively discourages the interviewers for their internal hires to share information early in the process. Instead he has team members email their ratings and feedback to one singular person, who will collect and share back the information once all interviewers have opined.

Finally, the hiring managers should take note of the average score for a candidate. I’m not suggesting that she should then follow it blindly; the process is not an anonymous ballot. Instead, it’s meant to lead to richer, unbiased and uncensored discussions to help decision makers take note of information they might have missed otherwise. Therefore, also pay attention to ratings that deviate from the average and the stated explanation for these scores. At this point, it is OK to have a lively discussion during a group huddle with the purpose to influence and be influenced by others. If interviewers want to change their scores, let them do so. But they should also know it’s OK to not conform with the group, whether they want to stick with their original opinion or take a new stance.

Using this approach, I’ve seen candidates who the most senior team members were championing to be moved to a second spot, and less outspoken members of a hiring committee speak up and convince the other members why they should pay more attention to another candidate.

Most senior executives I’ve worked with have believed they are mature enough to listen to everyone and not be negatively influenced by each other. I don’t doubt their sincerity in this. I have, however, not seen any evidence suggesting that executives are immune to being influenced by a group. When being part of discussions when the above process has been applied in decisions ranging from CEO hires to hedge fund investments, I have observed healthier discussions that are not overly influenced by the most charismatic person.

Author Atta Tarki is the founder and CEO of specialized executive-search and project-based staffing firm ECA. He is also the co-author of the upcoming book, Evidence Based Recruiting.