Californians for Homeownership, a nonprofit organization sponsored by the California Association of Realtors (CAR) that aims to address California’s housing crisis through impact litigation, today announced that it has filed a lawsuit against the City of Huntington Beach. The lawsuit challenges the rejection of a 48-unit mixed-income condominium project. This is the organization’s first lawsuit under California’sHousing Accountability Act, also called the “anti-NIMBY law.” The law prohibits cities from denying zoning-compliant housing development projects.

“Huntington Beach put the anti-housing views of its residents over the region’s urgent need for more housing, rejecting a project that would have helped 48 families realize their dreams of California homeownership,” said C.A.R. President Jared Martin. “Cities like Huntington Beach need to understand that there are consequences for violating state housing law.”

California is in the midst of a severe housing access and affordability crisis. The state has a housing deficit of 2 million to 3.5 million homes and ranks 49th out of 50 states in the number of housing units per capita.

To address the crisis, the state has long had a practice of determining regional housing needs and requiring cities to identify areas where housing can be developed to meet those needs. Anti-housing cities have subverted these rules in increasingly creative ways. One common technique is to create zoning criteria that are so vague and subjective that they allow the city to veto any project at will. In response, the state has developed laws to ensure that cities live up to their land use plans and to penalize cities if their plans do not generate adequate housing.

The Housing Accountability Act is one such law. It requires cities to use specific, objective criteria to assess potential housing developments. It also makes it difficult for elected officials to overrule the assessment of a project made by a city’s professional staff. These rules give developers the predictability they need to invest time and money into plans for a potential housing development. The law also allows nonprofits like Californians for Homeownership to sue on behalf of the public interest in increased housing, without the participation of the developer.

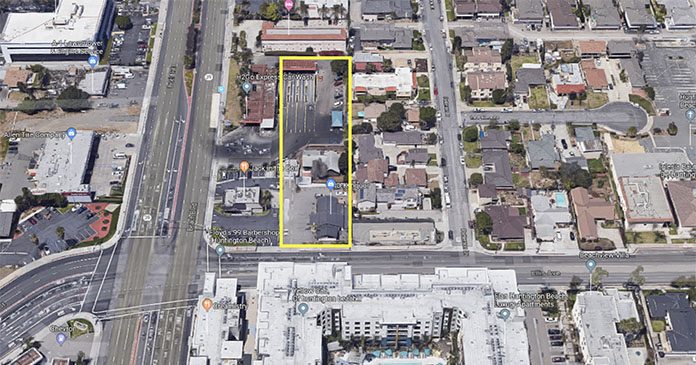

The proposed project at issue in the nonprofit’s lawsuit would offer 48 condominiums in a four-story, medium-density building with a ground floor coffee shop. Five of the units (10 percent) would provide deed-restricted affordable housing. The building would replace a liquor store, a single-family home, and part of a car wash on a lot fronting onto Ellis Avenue near the intersection with Beach Boulevard—two major thoroughfares in the city. Under the city’s Beach and Edinger Corridors Specific Plan, this intersection was selected to become one of the hubs of a walkable urban neighborhood with shops and multifamily housing. The project site is located directly across Ellis Avenue from a 274-unit apartment complex built in 2015 at approximately twice the density of the proposed project.

“This project is located exactly where the city said housing developers should be looking to build,” said Matthew Gelfand, the group’s in-house litigator. “The developer worked closely with the city to design a beautiful zoning-compliant project. It earned the recommendation of city staff, who found that it met all of the city’s requirements.”

But when the project went before the Planning Commission, it faced significant opposition from residents. The Commission parroted the public’s comments. One planning commissioner observed that although the project “does meet the appropriate code guidelines,” it should be denied because it doesn’t fit the “spirit” of the city’s rules. He also faulted the developer for not meeting with the planning commissioners outside of the public meeting process and for not offering high-tech previews of the project—for example, using virtual reality goggles. The Commission directed staff to return with reasons to reject the project.

The city’s final findings for denial focused on traffic impacts, even though the project’s traffic analysis showed that during peak hours it would generate only one car every two to three minutes along Ellis Avenue, a thoroughfare with four lanes in the relevant direction of travel. The city also faulted the project for not including more retail space even though additional retail space would create drastically higher vehicular traffic to and from the project.

“The findings were pretextual,” Gelfand said. “The complaints from neighbors and the Planning Commission weren’t focused on the specifics of this project, but on the very idea of allowing more people to live along Ellis Avenue even though that’s exactly where the city is telling developers to build. At the end of the day, the Planning Commission came up with vague reasons that could be used to deny any zoning-compliant housing development on the site. The city’s findings are internally inconsistent and don’t pass the most basic ‘smell test,’ let alone the high bar set by the Housing Accountability Act.”

Huntington Beach is well-practiced at obstructing housing development. The State of California was recently forced to sue the city over its decision to unlawfully reduce the number of new units allowed in the Beach and Edinger Corridors Specific Plan area without identifying alternative housing sites elsewhere in the city. For its own part, the city filed lawsuits to invalidate several state housing laws, and it recently announced it will seek to invalidate two more. Those lawsuits are ongoing.

In its lawsuit, Californians for Homeownership seeks an order overturning the city’s denial, as well as reimbursement for its costs and attorneys’ fees.

Source: California Association of Realtors