Utility management and benchmarking systems help property managers avoid fees, make smart investments and comply with the law.

Here’s one way to pay a lot less for power and water at apartment properties—stop paying late fees.

“Utility companies are notorious,” says Jason Lindwall, SVP, utility management solutions for RealPage, Inc. “They drive as much in late fees as they can—it’s the one unregulated part of their business.”

Utilities often give busy property managers just a few days to pay their bills. The resulting fines can easily add up to tens of thousands of dollars a year. But utility management services can now collect billing information from utility companies electronically and help apartment companies pay their bills on time.

These utility management systems also gather data many apartment companies already need to track regarding power and water used at their properties. Some need the numbers to satisfy tough requirements set by many cities. Others want to qualify for a low interest rate on a permanent loan through a “green lending” program, or earn a valuable “green building” certification.

Finally, data gathered by utility management and benchmarking systems can help properties owners find and fix problems like leaks, decide whether it’s time to replace aging equipment and determine whether large investments in energy-efficient renovations are worth the cost.

Stop late fees now

Before it began to use a utility management service, one national apartment company had been racking up more than $50,000 a year in late fees to utility companies, according to Martin Levkus, regional director of sales at Yardi. That’s an appalling amount to lose on an avoidable expense, even though the cost is spread over the more than 10,000 apartments managed by the company. (Yardi declined to name its client.)

“Utility companies are notoriously known for short payment terms (often just 15 days instead of 20-25 days),” says Levkus. “Many outsource printing of the bills… there are many jurisdictions where clients have less than five to seven days to pay.”

Even the best property managers may not turn around what appear to be routine bills that quickly. “Utility bills are six or seven on their priority list,” says Levkus. Also, utility companies have a powerful motivation to do things that make property managers late to pay. “Utility companies get 20 percent to 25 percent of their budget in late fees, so they have no intention of making it easier.”

Utility management systems can help. “With features like billing management, owners can avoid late fees and extra charges,” says Dennis Hidalgo, manager, housing energy and sustainability for Volunteers of America, which operates more than 12,900 units of rental housing in the U.S.

Utility management services can also find expensive errors in utility bills and even generate a final bill when tenants move out, to avoid losing revenue. Perhaps most importantly, utility management can help owners identify improvement that will help apartment properties operate more efficiently, earning more net operating income and creating a better return for investors.

“They can help us identify performance issues and make improvements to mitigate costs,” says Hidalgo.

Managers already have to benchmark many properties

Utility management services also gather a lot of data the many apartment managers already need.

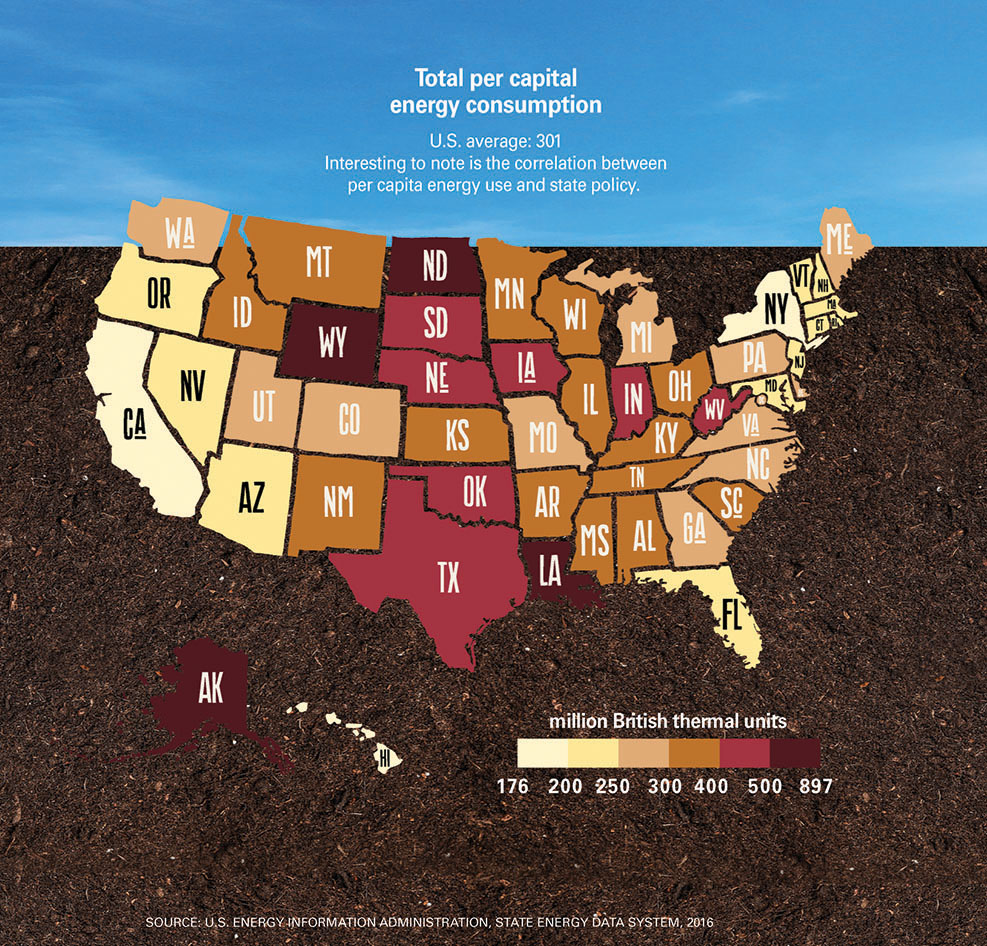

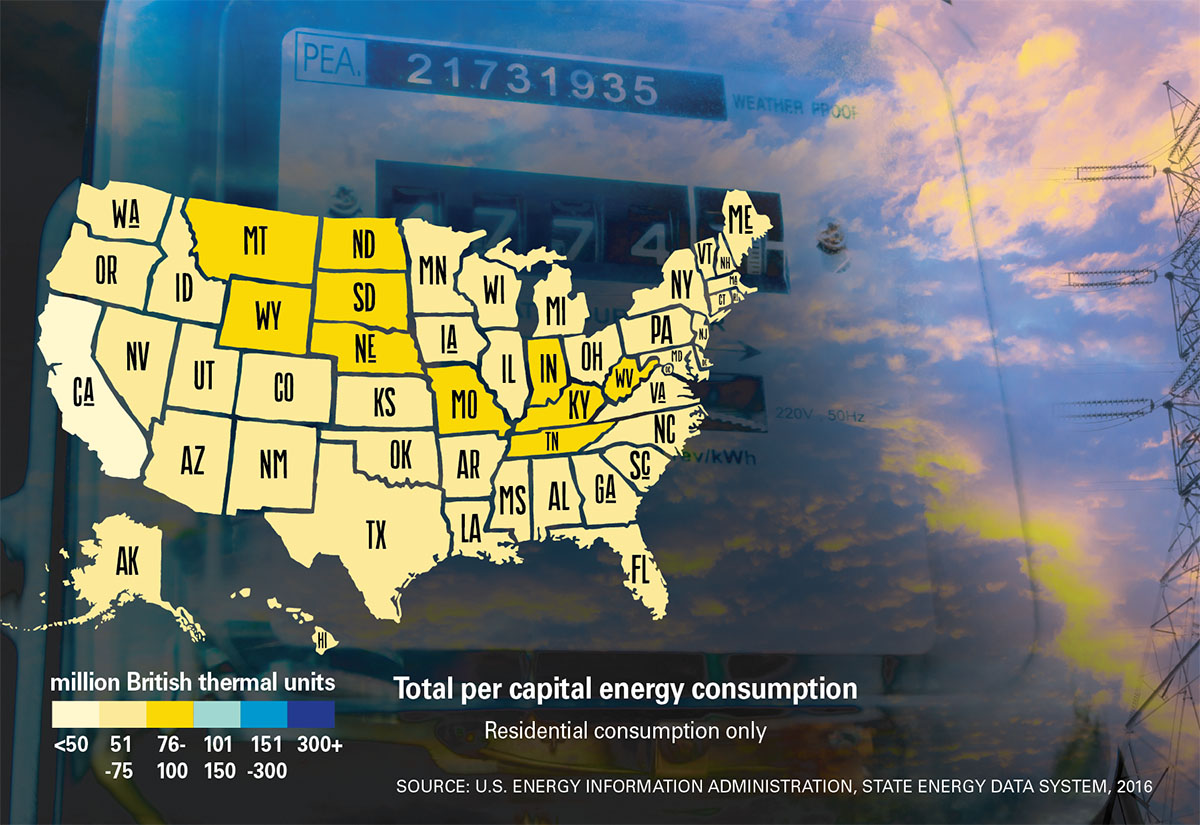

Across the U.S., apartment owners now “benchmark” the amount of water and power used at hundreds of thousands of properties. In this case, benchmarking means quite simply that owners measure the amount of power or water used at these properties and compare that amount against some benchmark—usually either the amount used in the past at the same building or in comparable apartment buildings nearby.

A growing patchwork of programs and new laws now require owners to benchmark properties in much of the U.S. “If you have a diversified portfolio you are going to have to benchmark,” says Andrew White, sustainability program manager, RE Tech Advisors.

Many jurisdictions now require properties to benchmark—including 35 cities, counties and the entire State of California, according to the Institute for Market Transformation. That includes New York City, Washington, D.C., Boston and Seattle, in addition to smaller cities like Des Moines, Iowa, and Fort Collins, Colo. “It’s really starting to spread,” says White.

Owners often benchmark to qualify for green building certifications, which are now important to help properties get the attention of potential investors. Owners can’t qualify the most desirable green certifications without first winning an Energy Star rating from the U.S. Department of Energy.

“If I want to resell my property, I need a good Energy Star score,” says Levkus. “We have over 2,000 properties using us to do benchmarking for Energy Star… Typically they are well-maintained buildings. It is one of the things that investors are looking at.”

To get and keep an Energy Star certification, a building must benchmark its energy use to show that it is more energy efficient than 75 percent of local buildings—which works out to a score of 75 or higher.

Property owners also benchmark the utilities used at thousands of buildings to prove they are meeting commitments made to qualify for programs like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac’s green lending programs. These programs offer apartment properties lower interest rates on permanent loans to borrowers that promise to significantly reduce their energy use.

“For the first couple year Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were not enforcing these commitments,” says RealPage’s Lindwall. But in the last 12 months, the agencies have been demanding that properties either demonstrate that they have cut their utility use, or surrender their lower interest rates—which were often fixed 30 to 35 basis points lower than the rates offered to comparable properties.

How to benchmark

Technically, all a company needs to benchmark an apartment property is an Excel spreadsheet and a stack of utility bills. However, benchmarking becomes much more complicated if the apartment residents pay for their own utility use, measured with a separate sub-meter for each apartment.

“We are seeing a trend towards submetering,” says Levkus. “Many cities and local jurisdictions are mandating sub-metering in new multifamily construction projects.”

The programs and local laws that require benchmarking typically ask property owners to submit information on the utilities used in an entire building. So owners often have to work with utility companies to get the information on how much electricity is used by residents.

The “Energy Star Portfolio Manager” system created by the Environmental Protection Agency can help property managers get more insight into a building’s utility bills. The system helps owners evaluate the energy used at their buildings in light of the most recent weather data and in comparison to other buildings nearby. It also takes into account the occupancy rate at the building. For example, the winter in Boston was very mild in early 2020. A typical building should have used much less energy, unless it had begun leaking a lot of heat. “If my energy use was flat in that year, in that place, that is really bad,” says White.

Other benchmarking systems go deeper—the two most prominent are Energy Scorecards and WegoWise, a benchmarking system created by AppFolio, according to Rebecca Schaaf, senior vice president of energy for the National Affordable Housing Trust (NAHT), an affiliate of Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future. Like Portfolio Manager, they help owners evaluate the energy used at their buildings. They also give owners insights into where to target retrofits. They can even send automatic alerts when the systems notice high consumption on utility bills.

Many utility companies can feed these systems data that aggregates the utility use for entire buildings, no matter how many individual payers receive separate bills. “Some utilities provide the data in a spreadsheet format and others upload the data directly to the EPA’s Portfolio Manager website,” says NAHT’s Schaaf.

However, managers like VOA, which have properties in a variety of jurisdictions, still need to do some work. The WegoWise system imports most of the data directly from utility websites. A few of VOA’s properties in small municipalities, however, need to email copies of their bills monthly, because their utility provider does not have a compatible online platform. “I handle the collection and submission of this data to comply with the ordinances,” says Hidalgo.

In praise of incrementalism

Once they have gathered all of this data, benchmarking and utility management systems can help property owners plan to invest in potential renovations at their buildings.

“A lot of customers are doing this to check a box,” says RealPage’s Lindwall. “We are now taking that data and presenting it to them on opportunities.”

Utilities are the third largest cost for property managers, larger than every other cost other than “payroll” and “mortgage.” And this cost is likely to rise in the future. “Utility companies have not been staying up on infrastructure costs and maintenance. They’ve had to spend a lot of money,” says Lindwall. These costs are likely to get passed on to building owners and residents.

To help fight these rising costs, property owners who sign on to the Better Buildings Challenge, created by the U.S. Department of Energy, commit to cut the energy used at their buildings by 20 percent over ten years, or roughly 2 percent a year. That level of incremental change is something that many property owners can reasonably maintain.

“We typically see somewhat around 2 percent per year in energy savings on a portfolio level for our clients,” says White. “As people have achieved their goals they go on to set new goals.”

Local officials may ask property owners to do more—much, much more. In New York City, large and medium-sized buildings must reduce the carbon emissions caused by their utility use by 40 percent by 2030. By 2050, lawmakers plan to cut the overall greenhouse gas emissions from New York City by 80 percent from the City’s levels in 2005.

A property owner could invest in a gut-rehab that cuts the energy used at a building all the way down to net-zero. However, that kind of radical rehab may be too expensive for many owners. “It does take money to get to zero. With new technology and new expertise required, it is difficult to cut everything overnight,” says White. “There is a middle strategy that often is the most economically prudent.”

Utility management and benchmarking systems may help owners identify strategies with the fastest return on investment. For example, simply sub-metering for electricity and water has proven to be a very effective way to cut utility usage. “If a property is sub-metered for water, we typically see a 20 percent drop in water usage,” says Lindwall.

Sub-metering can also put the cost of those utilities in the center of the negotiations that property managers have with potential tenants over the total cost to rent an apartment. That can help efficient buildings earn extra attention from prospective residents.

“It is something that residents are clamoring for,” says White. “Some will choose green certified property over non-green-certified. Some ask about utility costs—the total cost to live in an apartment.”

Wireless sensors stop leaks, solve problems

If property owners are willing to invest in new, wireless sensors, then utility management systems can also provide much faster information on the energy and water used at a building.

“We are able to collect 5, 15, 20, 30-minute interval data and report on it,” says Yardi’s Levkus. That is particularly useful if the sensors report an unusual amount of water or electricity use. That could be the first sign of potentially expensive problem, like leaking water or damaged equipment.

“If you’re seeing consumption of water at 2 a.m. … The data can trigger an exception and generate a work order,” says Levkus. Potential problems could range from leaking toilets to leaks in swimming pools.

Utility management systems could also use this data to schedule heating and air conditioning to better reflect the needs of tenants. “This technology would have let us see actual consumption, and react to it right away instead of waiting for the next utility bill,” says Hidalgo. “These sensors would also let us know what specific piece of equipment is responsible for any performance issues.”

The individual sensors can be relatively inexpensive—as little at $20 each. However, the cost grows depending on how many are needed for each apartment. “Unfortunately, this technology is cost prohibitive for multifamily, given the large number of access points that would need to be monitored,” says Hidalgo.

The cost is especially high in properties that are not already wired to provide wireless Internet, which the sensors can use to communicate to the utility management system. “Gateways” can cost more than $1,000 per unit. “Lack of widespread access to WiFi is a barrier as well,” says Schaaf.

The cost can rise especially high in a new apartment tower. “High-rises with concrete walls are more challenging and it could more costly to install and use wireless solution,” says Levkus.

Author Bendix Anderson

![shutterstock_765366799 [Converted]](https://yieldpro.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Apartment-investors-dig-data.jpg)