State and local governments have closed businesses across the country in response to COVID-19, putting millions of Americans out of work. Right now, those Americans’ biggest concerns are keeping a roof over their heads and feeding their families.

Against that backdrop of economic anxiety, Sen. Barnie Sanders tweeted, “It is time to #CancelRent and #CancelMortgages until this crisis is over.” He’s just one of the politicians around the country pushing such plans. State legislators, county supervisors and city councils have suggested the same.

But these rent holiday and forgiveness schemes are flatly unconstitutional and are likely to cause more long-term harm to the economy.

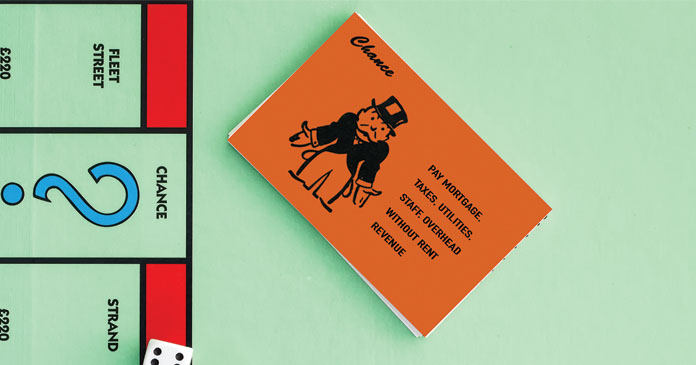

Keep in mind that for every renter hurt by the economic slowdown, there is also a property owner who will likely be losing rent payments for the same reason. They have expenses, too: mortgage payments, taxes, insurance, maintenance and utilities, all of which are due whether the rent is paid or not. Some of them face financial ruin if they endure long periods of time without receiving rent revenue. Shifting the burdens of the pandemic off renters to the shoulders of politically-disfavored property owners is a profound injustice.

Under the current emergency, what is the right way to help renters while protecting the rights of the property owners to the rent they are due?

In normal times, the owner can use court procedures to evict a non-paying tenant, which can be a time-consuming and expensive process. Residents have a variety of defenses against the eviction, and contract law generally recognizes those defenses in unique circumstances—like the current wave of government business closures.

In the current emergency, it is reasonable that many residents would be concerned about eviction because so many of them have lost income and cannot stay current with their rent. It’s no surprise that many city and state governments would want to protect the interests of these renters.

It also should surprise no one that too many of these governments seek to impose heavy-handed universal prohibitions on evictions as a policy response to the business closures imposed by these same government officials.

Typically, when a renter cannot pay rent, the landlord can look to other aspiring prospects who can move in once the non-paying resident has been evicted. But in the current extraordinary environment—in which the government has shut down most businesses and ordered most people to stay home—almost nobody is a potential new renter, and landlords no longer have good options but to stick with the residents they have, rent or no.

In fact, despite the handwringing in the media, there has been little evidence thus far of a national wave of mass evictions casting renters into the streets.

But there are many other reasons an owner may need to evict, and not all of them stem from economic stress. Some residents damage the homes they rent, engage in offensive or dangerous behavior, or break the law in ways that create liability for the property owner. Reasonable people would generally agree that property owners have a basis to evict these renters quite aside from their ability to pay rent, especially residents who pose a threat to people or property.

There may be a role for local governments to protect renters when those governments themselves have caused the economic harm the renters are experiencing. But officials should be coupling those protections for renters with relief from property tax obligations and government service and utility payments for all property owners, on an equal basis.

Preventing all evictions, for any reason (as some local ordinances effectively do), while doing nothing to shield property owners, is a dangerous over-reaction to the scope of the problems posed by the current emergency.

A growing number of cities, egged on by radical activists, are taking an even more damaging step: trying to cancel the obligation to pay rent entirely. The Constitution requires that rent control ordinances at least afford property owners a fair return on their property and allow them to exit the rental market if they want. Without these protections, cities are commandeering private property to serve as public housing and are liable for uncompensated takings of the owners’ property.

Vaporizing the obligation to pay rent, and the ability to evict non-paying residents violates both of those rules. If city councils go too far to protect renters for political reasons, they may find themselves legally on the hook for taking the landlords’ rent.

Officials should step very carefully with these kinds of measures and avoid stomping on constitutional rights. At the very least, they should be gathering data on the pace and number of eviction actions actually filed, to see whether the situation even warrants such extreme action.

Author Tony Francois is a senior attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation. PLF litigates nationwide to achieve court victories enforcing the Constitution’s guarantee of individual liberty.