There’s a scene in the HBO drama The Wire where several Baltimore homicide detectives come to the realization that the murderous gangster they’ve been chasing for the better part of three seasons might have moved on to a new profession.

“Seems that Stringer Bell is worse than a drug dealer,” says one. “He’s a developer,” finishes another.

The line is a joke, but it’s also an important piece of exposition: The money from Baltimore’s drug trade is fueling a corrupt redevelopment of the city that will wipe away what little is left of deeply rooted (but deeply troubled) communities.

The Wire was a groundbreaking show in many ways. Its casting of land developers in the role of shadowy villains is the most ordinary thing about it. In Hollywood, a developer is almost always a bad guy.

Throughout television and film, property mongers are deployed again and again as antagonists whose schemes to build a new condo or supermarket must be defeated at all costs. The trope transcends genre boundaries, giving a work’s protagonists someone to fight against and something to fight for. Developers menace characters in goofy comedies and serious serial dramas. They appear in dark horror movies, children’s cartoons, and blockbuster sci-fi flicks. Whether it’s a gentle animated feature like Up or an alien war film like Avatar, a comedy like Barber Shop 2 or an absurdist musical like The Blues Brothers, chances are someone trying to build something somewhere is the threat that sets the whole plot in motion.

The trend is pervasive enough that there’s a whole blog, Evil Developer Movies, cataloging bad-guy builders. The website TV Tropes has labeled this particular cliché “saving the orphanage”—alternatively known as “saving the community center” or “saving the home”—and finds examples of it in everything from anime to professional wrestling. In the movies and on television, evil developers are everywhere.

Common bad guy types such as mob bosses, drug dealers, and even terrorists have earned some level of on-screen atonement, or at least gained some personal depth, as compelling, complicated antiheros. But the scumbags trying to finance new apartment buildings and shopping malls haven’t been so lucky. Perhaps that’s too much to expect when those few moviegoers who do care about land-use policy spend their time outside the theater petitioning for increasingly restrictive zoning codes and protesting new construction in their neighborhoods (and, in the time of coronavirus, refusing to pay rent on units that have already been built).

It’s a pop-culture paradox: Even as demand for homes has skyrocketed across the country, the people who actually build them are consistently portrayed as jerks. The more housing we need, the less we like the people who provide it.

The big question is: Why? Why is the developer always cast as the slimy, unscrupulous, corner-cutting, occasionally genocidal villain?

One reason is Hollywood’s traditional bias against businessmen. Popular movies are, not surprisingly, populist. Audiences never seem to tire of rooting against wealthy evildoers concerned only with growing their stacks. The rock-bottom reputation of developers in real life, colored by the often sleazy, occasionally corrupt nature of their industry, certainly does nothing to endear their fictional avatars to moviegoers.

Meanwhile, conventional movie plots demand clear-cut heroes and villains and succinct, easy-to-visualize resolutions. This leads filmmakers to emphasize the destructive aspects of the development business while burying the considerable benefits it provides in the form of new homes, shopfronts, and offices that allow people, businesses, and whole communities to grow and thrive.

Characters who have to unite to defeat an outside threat are characters viewers can root for. Sometimes that threat is an alien invasion. Other times it’s an alien-looking condo building. Unlike new construction’s potential to stabilize rents and provide a wider array of housing options, the immediate threat of destruction to an idyllic small town is easy to see, and thus easy to put on film.

The consistent on-screen portrayal of developers as villains tells us about more than movies. Politics is about spinning compelling narratives, too. The easy typecasting of people who build as bad guys might help explain why NIMBY (not in my backyard) interests are often able to win the policy battles over urban growth and development, if not the actual arguments.

A complicated and ugly process

Understanding the evil-developer trope requires understanding its history. One place to start would be with the Depression-era movies of Frank Capra.

Capra directed two of the first major films with an evil-developer antagonist: 1938s You Can’t Take It With You and the 1946 Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life. The former involves an unscrupulous arms manufacturer whose plan to buy up the land near his factory is thwarted by a holdout homeowner. The latter gives us one of the most iconic rich-guy villains in movie history: Mr. Potter.

Potter, the cold-hearted and exploitative slumlord of Bedford Falls, engages in everything from attempted bribery to outright theft in an effort to stop the saintly George Bailey, played by Jimmy Stewart, from providing Potter’s tenants with the option of affordable, quality suburban housing.

That message surely meshed well with moviegoers of the 40s, who had suffered through a prolonged Depression commonly believed to have been caused by capitalist risk taking. The collective deprivation during World War II probably made Potter’s single-minded pursuit of wealth seem all the more crass and selfish.

This early iteration of developer-as-villain is complicated by the fact that Bailey himself is also basically a developer. The conflict in the film is therefore between two rival businessmen—and, ultimately, within Bailey himself as he struggles to appraise his own value in the world. Yet the main takeaway from the film is that the generosity and open-heartedness that contribute to Bailey’s professional failures are also what make him an asset to his family and community—someone worthy, in the end, of redemption. The implied flip side of this story’s moral is that being a good developer requires being a bad person.

In a 2017 dissection of Capra’s influence on the evil-developer formula for CityLab, Mark Hogan writes that “George Bailey, for all his other virtues, isn’t much of a businessperson. His bank needs to be bailed out twice over the course of the film. The holiday lesson here: If you want to make money, you need to be Mr. Potter.”

According to Hogan, a more perfected version of this trope didn’t arrive until a few decades later. “The heyday of the evil developer movie was the 1980s,” he writes. Treating real estate developers as villains fit well with the supposed dog-eat-dog capitalism of the time. “This was the era of the yuppie, when factories closed and Donald Trump thrived. It was also a time of real-life economic swings, from the high inflation and interest rates of the early 1980s—followed by a recession—to the Savings and Loan Crisis of the last part of the decade.”

One need not agree with Hogan’s characterization of the 80s-era economy to see how such a view could color the attitudes of film producers and watchers, making them hungry for tales where the Reaganite capitalists are portrayed as soulless profit seekers. This obviously extends beyond developers to other creatures of finance: your Gordon Geckos and Patrick Batemans, wealthy Wall Street workers who loudly and explicitly tout the productive aspects of greed and free enterprise while bringing nothing but destruction to the people around them.

Yet evil developers in this era show up in everything from horror movies like Poltergeist to comedies like The Goonies to horror-comedies like People Under the Stairs (technically not an 80s film, as it was released in 1991). The sheer frequency suggests there’s something special about this particular wealthy antagonist that goes beyond Hollywood’s baseline loathing of Big Business.

One explanation might be that developers are easy to cast as shady villains in fiction because they’re often shady in reality. The business of real estate development, after all, is a mess of red tape, regulation, and crony-dominated approval processes.

“From zoning permits to eminent domain to tax abatement, urban development as it exists today is a complicated and ugly process unintentionally designed to benefit developers with the fewest qualms about greasing palms and buying off opposition,” researcher Nolan Gray writes at Market Urbanism. As Michael Manville and Paavo Monkkonen, two urban planning professors at UCLA, put it in their 2018 study of anti-development attitudes, “a combination of high land costs and complex regulations often makes development difficult. These circumstances could select for developers who are both affluent and out-of-step with conventional ways of behaving: only deep-pocketed, hard-charging and confrontational people will be willing and able to lobby elected officials and get rules changed in order to build.” It’s a system that’s practically designed to reward the Potters of the world while squeezing out the Baileys.

With developers’ real-life reputations so low, is it any wonder that audiences would be receptive to fictional portrayals of them doing awful things—and that we would be primed to root for their downfall? This explanation fits neatly with a common formula for bad-guy-developer movies: the one where an antagonist crafts some truly heinous scheme to prop up his real estate investment.

Probably the most obvious example of this, as Hogan notes, is 1978’s Superman, a story in which Lex Luther plots to sink the entire West Coast into the Pacific Ocean as part of a plan to turn his otherwise valueless holdings of desert land into prime beachfront property.

In a 2006 Superman reboot heavily indebted to the 70s movie, Luther doubles down on his evil schemes by trying to create entirely new virgin landmasses ripe for development. Unfortunately, the land is to come at the expense of existing continents and the people who live on them. In both portrayals, the developer is literally a comic-book supervillain whose development strategy is a form of profit-driven mass murder.

There’s a similar dynamic in the best-forgotten 1990 movie Darkman, a comic book–like film from the future director of 2002’s Spider-Man in which a mobbed-up developer tries to kill Liam Neeson (playing a scientist) to conceal the fact that he bribed the zoning commission to secure permission for his redevelopment of the city’s dilapidated waterfront. Unfortunately for the bad guy—and, frankly, for the waterfront—Neeson is only maimed in the attempted hit. He spends the rest of the movie on a rampage of revenge.

The message for audiences is clear: The benefits of new development accrue solely to annoying and often malevolent characters. The new spaces they create for people to live, work, and play are at best an accidental byproduct of the villain’s usually violent schemes for self-enrichment. The buildings themselves are mere inanimate objects, little more than MacGuffins. The actual people who might inhabit them and enjoy their amenities are never shown.

No corruption required

As compelling as this explanation is, it’s also incomplete. It’s true that a lot of opposition to new development is motivated by a not-totally-unfounded view of developers as crony capitalists. But a lot of it isn’t. NIMBYs rarely have qualms about opposing new projects that didn’t receive special favors—sometimes projects whose developers bent over backward to hand out concessions and community benefits.

A lot of movies make the developers bad guys even when no corruption or murder is involved. Their role as villains stems entirely from their attempts to build something new rather than any misdeeds they carried out to make their project happen.

New development almost always requires an element of creative destruction. To build a fancy new building, it’s often necessary to knock down the old one that stood in its place. On some level, we all accept this process as necessary and beneficial. At the same time, the long-run, dispersed benefits of change are a hard thing for our brains to really grasp. We focus on the most obvious effects happening around us, which often means focusing more on the immediate destruction and less on the later creation.

This is why, in real life, it’s easy to get a bunch of angry residents to show up at a city council meeting to protest the redevelopment of a neighborhood business and hard to get anyone to defend the new apartment building that will replace it. It’s a narrative that audiences are prone to accept in the fiction they consume as well, particularly in the time-constrained medium of film, where there’s less room to dwell on long-run effects and unseen benefits.

That fact helps explain the most common formula for an evil-developer film: the quirky yet tight-knit ensemble cast of characters pitted against a real estate tycoon threatening to destroy their beloved home or hangout, and with it our heroes’ sense of community and place. The Goonies—a movie in which a misfit band of kids tries to prevent the foreclosure and redevelopment of their families’ houses into a golf course by recovering a long-lost pirate treasure—is one example of this phenomenon. But there are many, many more, from One Crazy Summer to The Country Bears, that fit the bill.

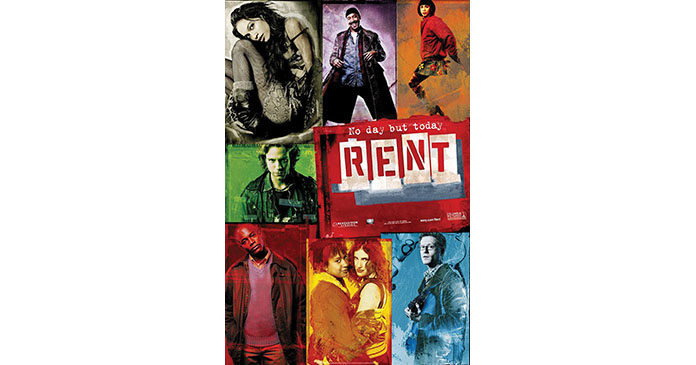

Sometimes in this formula the developer is corrupt or homicidal, but that’s hardly a requirement. More often, he’s just obnoxious. And sometimes he’s secretly the good guy, even if neither filmmakers nor audiences quite realize it. Take 2005’s Rent, adapted from a 1993 musical of the same name. The movie features a crew of supposedly lovable bohemians squaring off against their former roommate and current landlord, who is trying to evict them in order to redevelop their rundown building.

That might seem like a crummy thing to do to your friends. Yet the reason these characters are being evicted is that they’ve refused to pay rent for a whole year despite several of them having the means to do so. (One is a talented filmmaker with wealthy parents; another is a successful stripper.) The owner’s plans for the building are hardly soulless either. His goal is to redevelop the property into pricey condos, the proceeds from which will be used to finance the creation of an art studio. Nonetheless, viewers are clearly supposed to identify with and root for the nonpaying residents.

This dynamic shows how biased film is in favor of narratives about communities fighting against change from the outside. When counterprogramming touting the values of growth and dynamism does appear in these movies, it’s often put in the mouths of cynical characters who clearly don’t believe it (and whose words do little to win the audience over). When Strack, the evil developer in Darkman, tries to explain away his corruption by arguing that his City of the Future project will result in “acres of riverfront reclaimed from decay” and “thousands of jobs created,” we’re none too convinced by his good intentions. It doesn’t help that he delivers these lines while staring lustfully at a model of his proposed development as ominous music plays in the background. Strack is evil, and thus his plan to build new, usable space and create jobs must be evil too.

Development and its discontents

“Change is good” is the oft-repeated line of Sheck, the bad-guy developer in the film-length adaption of Nickelodeon’s Hey Arnold! That’s often true, but it’s much easier to sympathize with the protagonists in the movie who are resisting his attempts to bulldoze their neighborhood and who ask in response, “What’s wrong with leaving things the way they are?” Discounting the benefits of change, or treating them as tainted by the motivations of the villains who would bring them about, aligns the message of these works with the exclusionary preferences and politics of NIMBYs in real life—interests that care little for the wealth and opportunities new development might bring other people.

The ubiquity of anti-development narratives creates a revolving door between fact and fiction. Hollywood has given the country’s NIMBYs a lot of reasons to see themselves as the good guys.

In turn, their fights against new construction come to mirror the ones we see on screen, occasionally to an absurd degree. The characters in the Hey Arnold! movie, for instance, end up saving their block from destruction by uncovering a document proving that it was the site of a famous flashpoint in the Revolutionary War (the Tomato Incident).

This is a silly cartoon plot. But it isn’t too far from what happened in San Francisco in 2018, when a group of neighbors showed up to a real-life Board of Appeals hearing to argue that a vacant lot in their neighborhood couldn’t be turned into housing because a dirt path that ran through it—per their own amateur history work—had been used by early Spanish explorers in the region.

Unlike the kids in Hey Arnold!, these neighbors were never able to prove their claim. The developer was allowed to build his project, albeit a slightly smaller one than what he’d originally proposed.

At the heart of all these portrayals is a fantasy of a world without tradeoffs or even annoyances, one in which the only spaces anyone needs or wants are the ones they already have. It’s wishful thinking that works from the assumption that housing just exists without having to be provided.

Embedded in this worldview is a denial of the fact that preventing development and change means some people inevitably have to go without, while politically connected interest groups profit from higher rents and home values. The politicians who make this all possible are in turn rewarded with campaign donations and easy reelection. The bias is toward the status quo, and a corrupt one at that.

Surely someone would have liked to stop the initial creation of the working-class neighborhood where the characters in Hey Arnold! live. We, the audience, see only its most recent iteration, watching as its current inhabitants claim the moral high ground while desperately fighting any further change. The characters in Rent, meanwhile, assert that they shouldn’t have to pay their bills in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic—which isn’t too far from contemporary tenant activists arguing that COVID-19 obviates their own obligation to pay rent.

The ease with which we buy the evil-developer storyline is bad news, and not just for those of us hungry for a little more originality in filmmaking. Too many of America’s cities face shortages of housing, giving rise to unaffordable rents, unbearable commutes, and scandalous numbers of homeless people. The irony is that many of these problems originate with policies—from environmental review laws to density restrictions—intended to help “save the neighborhood.”

Chances are many of these policies would exist with or without the surfeit of movies and TV shows about crooked landowners. But the trope has clearly shaped our cultural script about development and its discontents, and little if any effort has been made to create a popular counternarrative.

The evil-developer trope gets the story backward. By championing anti-development, anti-growth policies, activists and politicians have made housing less available and less affordable, often while enriching themselves through the creation of artificial scarcity. Those few developers who are allowed to build get to share in these ill-gotten gains while doing irreparable harm to the reputation of an essential industry. The NIMBYs of the world may have benefited from Hollywood’s persistently negative portrayal of developers—but in real life, it’s clear that the NIMBYs are the villains.

Author Christian Britschgi, reason.com