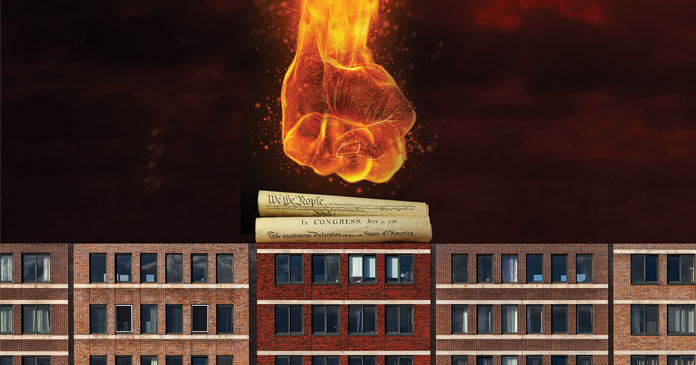

In the midst of the COVID pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) took the unprecedented step of banning evictions nation-wide, characterizing the action as a public health measure.

The action spawned lawsuits across the country as property owners impacted by the ban sought to protect their livelihoods by challenging the constitutionality of this step.

The property owners were aided by public interest law firms, including the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF). PLF lawyers Steve Simpson and Ethan Blevins are working on the cases and their updates are contained herein.

How did we get here?

Numerous emergency orders were issued at start of pandemic by all levels of government dealing with business closures and safety measures.

Many of these orders included state bans on evictions.

The CDC issued a declaration that evicting tenants could be detrimental to measures implemented to protect public health and to slow the spread of the virus that causes COVID-19. On that basis, it imposed a nation-wide eviction moratorium.

The CDC moratorium applied to people who made less than $99,000 dollars annually, hadn’t paid all their rent despite making efforts to do so, had suffered economic loss and would have been homeless or had to move in with others if evicted. The moratorium has now been extended through June 30, 2021.

Congress did pass, and President Trump signed, a law banning evictions through January 31, 2021. However, this law neither endorsed the CDC’s action nor provided legislative cover for the CDC to take action in the future.

Moratoriums: unprecedented

In justifying its power to impose a nation-wide eviction moratorium, the CDC is relying on the Public Health Services Act passed in the 1940s. This Act allows agencies to take action to prevent the cross-border transmission of disease. Actions specifically allowed include inspections, fumigation, pest extermination and destruction of animals.

The Act allows for the quarantine of individuals. Its catch-all language states that agencies may take other measures that are reasonable to prevent the transmission of disease across state lines.

While the act contains no explicit language dealing with housing or with evictions, the CDC asserts that the “other measures” clause gives it the authority it used in imposing the nation-wide eviction moratorium.

The PLF argues, and the CDC has not disputed, that such a broad reading of the provisions of the Act would give the CDC the authority to regulate nearly all activities of all individuals in the country, as long as they could argue that such regulation would slow the spread of some disease.

Let the courts decide

The PLF sued the Federal Government in Ohio and Louisiana. Other groups have also sued in other venues. The PLF asserted that the Act does not give the CDC authority to ban evictions and that the language contained in the Act does not support this overreach of power.

The PLF also argues that the CDC’s assertion that it can ban evictions is an example of the CDC making law, something that is not in the power of an executive branch agency. Instead, making law is under the exclusive purview of the legislative branch under the U.S. Constitution.

Further, the PLF argued that the CDC’s actions put in jeopardy the separation of powers within the Federal government, and also the separation of powers between the Federal government and the states. The CDC’s claim of broad power to regulate might also assume the power to override the decision of a state governor to ease restrictions in his state or to reopen his state’s economy.

The CDC prevailed in two early cases, including in the PLF’s case in Louisiana. That decision is being appealed. However, the CDC has now lost in three district courts and in one Court of Appeals. A court in Texas was the first to invalidate the rule. This was followed by the Skyworks decision, a PLF case in Ohio.

A court in Tennessee then also invalidated the decision. The Tennessee decision was challenged by the Federal Government since it more broadly banned the CDC’s eviction moratorium than did the others. The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals denied the Federal Government’s request for a stay of the Tennessee decision since the Court of Appeals believes that the federal Government will lose its appeal of the decision.

Skyworks and NAHB

In the Skyworks case, the PLF argued that “other measures” taken under the Act must be similar in kind to the measures that are explicitly allowed. The “other measure” clause does not give the CDC unlimited power to act. While the court agreed that the CDC had exceeded its authority in imposing the eviction ban, it did not grant an injunction preventing implementation of the moratorium nationwide.

The practical implication of the Skyworks win is that the PLF’s clients, which include the members of the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), are freed from complying with the CDC’s eviction ban.

The government’s position is that the declaration of the court that the CDC exceeded its authority in imposing the eviction ban, does not apply to anyone who was not party to the case.

The PLF asserts that the provisions of the Administrative Procedures Act mean that the declaration of the Northern Ohio District Court should cause the CDC’s eviction ban to be invalid across the country.

The PLF has asked the Northern Ohio District Court to make this explicit, but the court has not yet responded to this request.

Action at the state level

Ethan Blevins addressed the actions of individual states. About half of the states have enacted some sort of eviction moratorium, some of which have now expired. These moratoria vary greatly in their extent.

Some have hardship provisions, but some do not. Some have exceptions for lease violations other than non-payment, but some do not. Most moratoria don’t make any provision for hardship to the landlords.

Some moratoria have been imposed by governors, some by legislative bodies and some by the courts. Most eviction bans imposed by states and localities are harsher than the CDC eviction ban because they provide fewer exceptions for lease violations other than non-payment.

The PLF is suing in response to orders by the governor of Washington and by the Seattle City Council to ban eviction.

They are arguing that these actions are illegal under the contracts clause of the U.S. Constitution, which says that state and local governments cannot interfere with contracts freely entered into by local parties.

The PLF is also arguing against these orders under the takings clause of the U.S. constitution. This clause says that governments may not take private property without offering just compensation.

The PLF asserts that forcing private landlords to continue to “rent” their properties to people who are not paying rent, is effectively a taking of their property.

These issues are a long way from being settled but the fight continues.

Author Andrew Stephens