Few are executing new deals amid uncertainty about how high rates will go, what properties are worth, how much rents and operating costs will grow and whether a recession is coming.

Higher interest rates have shocked apartment investors—many seem uncertain what to do next.

“The level of activity across the board is lower than it has been in quite some time,” said Dave Borsos, vice president of capital markets for the National Multifamily Housing Council based in Washington, D.C. “When markets are in a bit of a turmoil that slows things down,”

Many investors are delaying—putting off —decisions that would require them to borrow money. Their biggest unanswered question is how high interest rates will rise—and how long they will stay high. But there is also uncertainty about what properties are worth in light of higher interest rates, how much rents and operating costs will grow and whether a recession is coming.

No wonder so many apartment investors seem to be hiding under their desks.

Of the relatively few financing deals investors have completed since the Federal Reserve began to push rates higher, many have been a struggle.

Some properties have to replace mature loans with new, higher-interest debt. Some buyers of apartment properties have taken new acquisition loans though few sellers are willing to lower their prices to meet the new reality. Some investors need to fill new holes in project budgets caused by higher interest rates and price inflation. Finally, some investors are going ahead with developments and value-added renovations, including many planned before interest rates rose to strain their construction budgets.

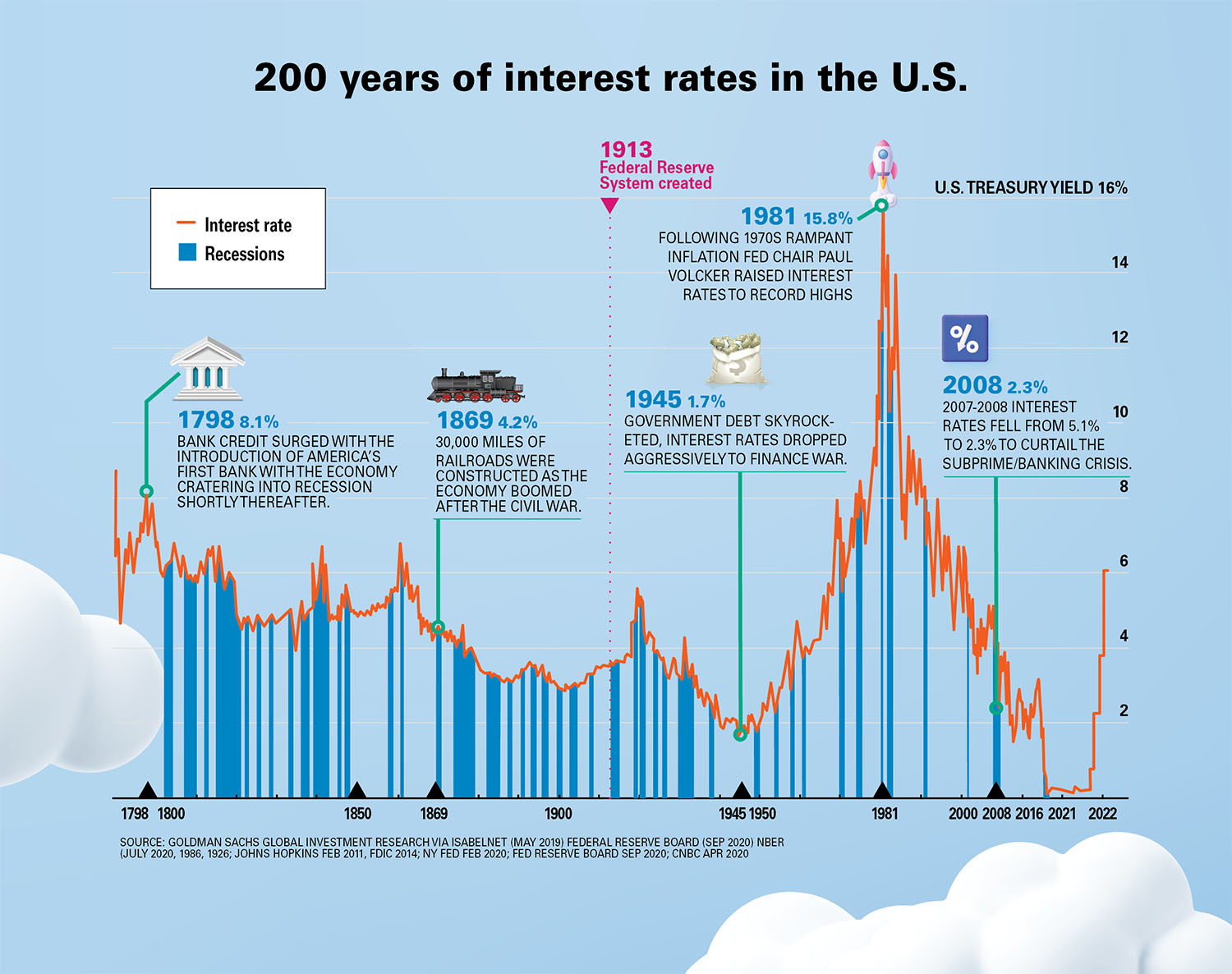

Shock to the financial system

Federal Reserve officials raised their benchmark, short-term, Fed Funds rate over and over in 2022 pushing interest rates for all types of loans higher by hundreds of basis points. By the first weeks of January, the Fed’s top target rate was 4.5 percent, up from just 0.25 percent at the beginning of the 2022.

The Fed is raising interest rates to fight rising prices, throwing cold water on an overheated U.S. economy. Most economists and investors expect the Fed to raise its interest rates at least once more by at least 25 basis points in January 2023, with another increase still possible later, despite growing pressure on the Fed to slow its pace of rate hikes.

“Current Fed posturing is that they’ll raise the Fed Funds rate to 5 percent and hold it there this year,” said Matt Vance senior director and Americas head of multifamily research for CBRE, working in the firm’s Chicago offices.

Some apartment investors are already hoping interest rates will soon stabilize and even fall again once Federal Reserve officials feel price inflation is under control. The overall Consumer Price Index actually fell slightly for the month of December.

“With the new year there is fresh optimism,” said Shlomi Ronen, managing principal and founder of Dekel Capital, based in Los Angeles. “Things had ground to a halt—but people are back in the office trying to figure things out.”

Construction loans for the daring

Apartment developers started construction on new apartments at an annualized rate of 463,000 a year in December 2022 continuing a building boom that began after the worst of the coronavirus pandemic, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Developers also started new apartments at a rate of more than 500,000 a year in August, September, October and November 2022.

High interest rates have not stopped these developers… yet. Many had been planning their projects long before interest rates began to rise. In early 2023, developer Blue Onyx plans to start construction on a new 70-unit building in East Orange, N.J. The project is still on track, despite rising interest rates.

“We planned so that if construction costs increase or financing costs increase, the project still makes sense,” said Jim Driscoll, senior vice president of development and acquisitions for Blue Onyx Companies. The project will also benefit from a local property tax abatement and relatively inexpensive land. “We had an opportunity to purchase a property from the City of East Orange that had not been in use.”

Interest rates are much, much higher for bridge finance and construction loans than just a year ago. In January 2023, banks offered interest rates floating 250-to-300 basis points over the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) for new, “best-quality” construction loans, bridge loans to low-leverage, light value-add redevelopments and loans to multifamily properties still in lease-up, according to Marcus & Millichap Capital Corporation.

That works out to all-in borrowing costs of about 7.0 to 7.5 percent. Those spreads are only slightly higher than spreads banks charged a year ago. But the benchmark SOFR rate has closely followed the Fed Funds rate as it rose increasing by more than 400 basis points.

“Heavier value-add deals or lesser quality construction loans are pricing at least 100 basis points higher or more,” said Marc Sznajderman, senior vice president and head of production for the Eastern region for Marcus & Millichap. “All-in costs for these deals start north of 8 percent and can be as high as 10 percent.”

The construction loans developers took out in January 2023 were also much harder to find than just a year ago.

“Many lenders that have historically lent in this space are on the sidelines,” said Jesse Weber, vice chairman for the Capital Markets Debt and Structured Finance Group at CBRE, working in the firm’s San Francisco offices.

Some of the biggest, national banks have already filled their balance sheets with all the real estate loans they are willing to carry. “Many have just elected to sit on the sidelines until markets improve or rates stabilize,” said Sznajderman.

“This created an opportunity for regional and local banks—though they are more limited in terms of overall lending levels,” said Susan Mello, executive vice president and head of capital markets for Walker & Dunlop, working in the firm’s offices in Englewood Cliffs, N.J.

Life companies now offer even more expensive constructions loans with interest rates floating 375-to-425 basis points over the SOFR, with an all-in floating interest rate of more than 8 percent in January, according to CBRE. “A few life companies have opted to start making shorter-term construction loans because they can get a higher yield than they can achieve on permanent loans,” said CBRE’s Weber.

Until very recently, private equity debt funds were some of the most aggressive lenders to apartment developers and value-added investors. Those debt funds are still in business and making loans. But their interest rates have risen even more quickly than those offered by banks. That’s because many debt funds often sell the loans they originate to bond investors as collateralized debt obligations. The yields on those securities have risen even faster than SOFR.

“The last debt fund deal we did had a 415-basis-point spread over SOFR,” said Brennen Degner, managing partner, CEO and co-founder of DB Capital Management, based in Playa Vista, Calif. That worked out to an all-in interest rate of more than 8 percent. “Debt funds are still around, but their pricing is almost like hard money at this point.”

In exchange for those high interest rates, debt funds still offer relatively large loans that can cover 80 to 85 percent of the cost of a project. In comparison, bank loans may typically have lower interest rates but rarely cover more than 70 percent, even if the borrower accepts a recourse loan.

“The debate owners face is whether to pay the higher spread for more loan proceeds or put in more equity and have a lower cost of debt capital,” said Weber.

The size of a construction or bridge loans is also limited by how much debt that property will be able to support once construction has finished.

“Lenders are underwriting to greater debt service coverage ratio on the back end, and if a borrower is not willing to offer recourse, the leverage amount is put under extra pressure,” said Mello.

“The most pressing challenge owners face when bridging financing to reposition a property is determining the optimal leverage point,” said Greg Ehrhardt, senior managing director of multifamily debt production for the Western Region at Newmark’s capital markets group, working in the firm’s Seattle offices. “They should be able to comfortably exit via refinance with conservative assumptions.”

Troubled deals need more equity

As interest rates rise and loans get smaller and smaller relative to the income produced by a property, apartment investors struggle to find new financing to fill the growing holes in their budgets. Some are contributing their own equity while others turn to private equity debt funds. Some may be forced to sell.

“Higher interest rates have already begun to create headwinds,” said Sznajderman. New construction and value-added renovations that took out aggressive loans and mezzanine financing at high leverage levels north of 80 percent are having the most problems—especially when it is time to pay off their maturing debt. “They may have to inject additional equity. We are starting to see a small number of maturity defaults as borrowers either are reluctant to put in additional cash or are seeing their equity evaporate as cap rates expand.”

“There are going to be people who got overextended, people who paid too much for land, people who put way too aggressive rent growth into their proformas because they wanted to get the deal,” said Borsos “That is going to happen on the margin. If you compare this to 2008, interest rates were higher then (and) people were way more levered up.”

Developers may also face challenges if they planned to sell their new buildings once the work was finished. The only potential buyers today might be expecting a steep discount because of the uncertainty in the marketplace.

“Your project is done, your construction loan is due and there is no market right now for an exit,” said Dekel Capital’s Ronen. “There is some interesting bridge-to-fixed-rate debt out there. The developer can continue to own and operate until the market returns to some kind of normal.”

Private equity debt funds now provide fixed-rate loans with flexible pre-payment in case borrowers exit before the minimum five-year term is completed. Interest rates are typically fixed at 200 basis points over the yield on five-year treasuries, said Ronen. The size of the loan is constrained by an 8 percent debt yield—which often works out to a loan that covers 70 percent of the value of a property.

These debt fund loans can even help new properties that are still leasing up. “They will fund pre-stabilization. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac won’t do that,” said Ronen.

Permanent loans still available

Interest rates also increased sharply for fixed-rate, permanent loans for apartment properties—though the increase has not been nearly as steep and high interest rates for permanent loans may have already peaked. Permanent loans are also relatively easy to find.

“Generally, lenders across the board are active in the permanent financing market, but with more conservative underwriting standards and while being more cautious overall,” said Sznajderman.

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae program lenders offer permanent loans with interest rates fixed 150 to 200 basis points over the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds. That typically works out to an all-in rate that ranges from 4.9 to 5.4 percent though apartment properties can receive a lower interest rate if they show relatively affordable rents and pledge to keep them affordable to working families.

Those interest rates are about 200 basis points higher than those offered just a year ago. The benchmark yield on 10-year Treasury bonds rose from 1.5 percent at the beginning of 2022 to a high of over 4 percent in October. Long-term rates then began to drop, even though the Fed kept raising its own short-term interest rates. The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasuries fell to 3.4 percent by January 19.

“We expect the yield on 10-year Treasuries to stabilize by mid-year this year and come down slightly in the second half of 2023, ending the year around 3.0 percent,” said Vance. “This stability in interest rates will rejuvenate buyers, sellers and lenders, and put incremental downward pressure on borrowing costs and should help lending terms stabilize this year.”

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae loans now usually cover 55 to 60 percent of the value of an apartment property. That’s much less than the maximum leverage allowed by agency loan programs, but it’s usually the largest high-interest loan properties can support and still meet the agencies’ debt service coverage ratio of 1.25x to 1.35x.

Banks still lending offer permanent loans that cover up to 65 percent of the value of an apartment property with all-in rates in the mid 5s and seeking debt service coverage of 1.25x, according to Marcus & Millichap.

Interest rates for permanent debt are now lower than rates for shorter term loans. That’s good news for long-term borrowers—but it’s a warning sign that the overall U.S. economy may be headed into a recession. That would create a whole new set of potential problems for apartment borrowers and loan underwriters, who now look skeptically at the projected rent growth for any apartment community.

“Many owners find themselves dealing with slowing rental increases and rising expenses,” said Weber.

However, most apartment markets are strong enough to weather a mild economic downturn, even if demand for apartments slackens just as developers finish hundreds of thousands of new units. “The occupancy numbers have been historically high,” said Borsos. “There were markets that reported over 99 percent occupancy—that’s unheard of.”

Author Bendix Anderson