If there is one word that best describes what’s impacting today’s multifamily market it’s uncertainty says National Apartment Association CEO Robert Pinnegar.

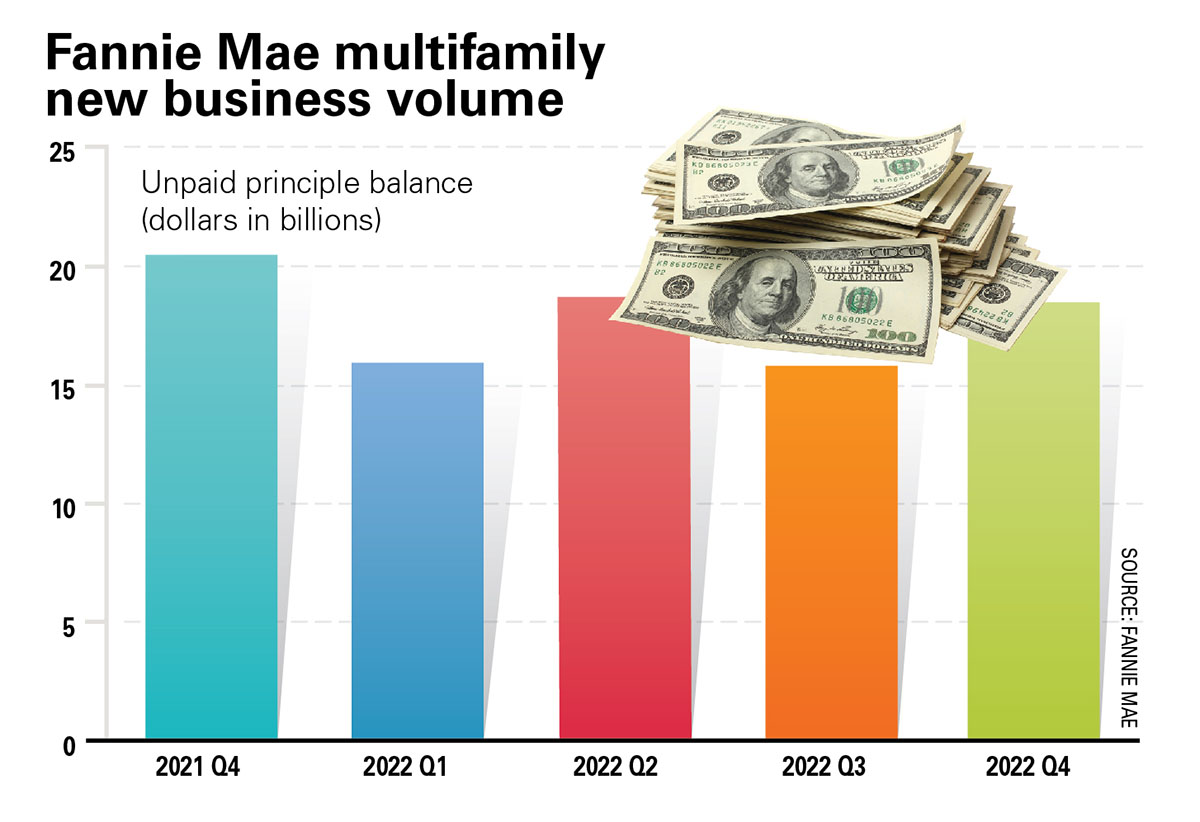

In the wake of the Federal Reserve’s seven interest rate hikes that began in March 2022 to stem inflation, multifamily players are unsure how to interpret the multifactorial headwinds affecting the industry.

These include slowing rent growth at the end of last year, which Pinnegar sees as simply a return to a more normal pattern from the episode of a post-COVID shift in population, and a rising vacancy rate predicted to reach approximately five percent by the end of the year.

Lending to the lack of certainty is a robust delivery pipeline—approximately 560,000 multifamily units are scheduled to come online by year’s end, the highest number of deliveries in more than 20 years, although a drop-off in permitting last November suggests the construction frenzy could taper off this year.

On the flip side, net absorption is forecast to reach its second highest level over the same period, suggesting new supply won’t remain vacant for long. Construction delays due to labor shortages could be a moderating factor.

And on the financing front, tightening lending criteria, lower leverage and skyrocketing capital costs are inflicting pain on demand.

“We’re also beginning to see significant increases in operating costs, some as a result of supply chain issues, and dramatic increases in insurance rates on the horizon as insurers and, more importantly, secondary insurers begin to question how much risk they want to take on in the U.S. as a result of environmental impacts. Think tornados in the Midwest, hurricanes in the Southwest and nor’easters.

“I heard a discussion on Bloomberg radio about secondary insurers’ exposure in North America and I thought, we probably won’t see the impact of this for another six months, but it’s likely to be significant when we do,” Pinnegar said.

In Florida alone since January 2020, a dozen insurance companies have gone out of business.

Recession question

Unpredictability still centers around the recession question. Will there or will there not be one and, if so, how deep? Two consecutive quarters of negative gross domestic product (GDP) is the typical categorization of recession, and, while that occurred earlier last year, GDP reports are often subject to long delays and big revisions, said financial expert Shawn Winslow in February 11 podcast.

Winslow explained that some market watchers choose to look at more current and leading data, specifically from four leading macro indicators—the Global Credit Impulse, the Conference Board Leading Indicator Index, the Philly Fed New Orders Index and the housing market itself, the latter of which represents between 12 percent and 15 percent of U.S. GDP and employment alone. All of these indexes point to a recession beginning somewhere between March and May of this year.

While industry pundits still disagree over the inevitability of a recession, the field is most divided on its severity. Will the landing be soft or hard?

“In the beginning of this current trajectory, everyone was betting on a soft landing. Then interest rates spiked dramatically and everyone said it was going to be a hard landing. But now I am hearing the soft-landing prediction again. I’m not sure anyone knows for sure, but if we do see a soft landing it will be good for the overall business community and good for multifamily,” said Pinnegar.

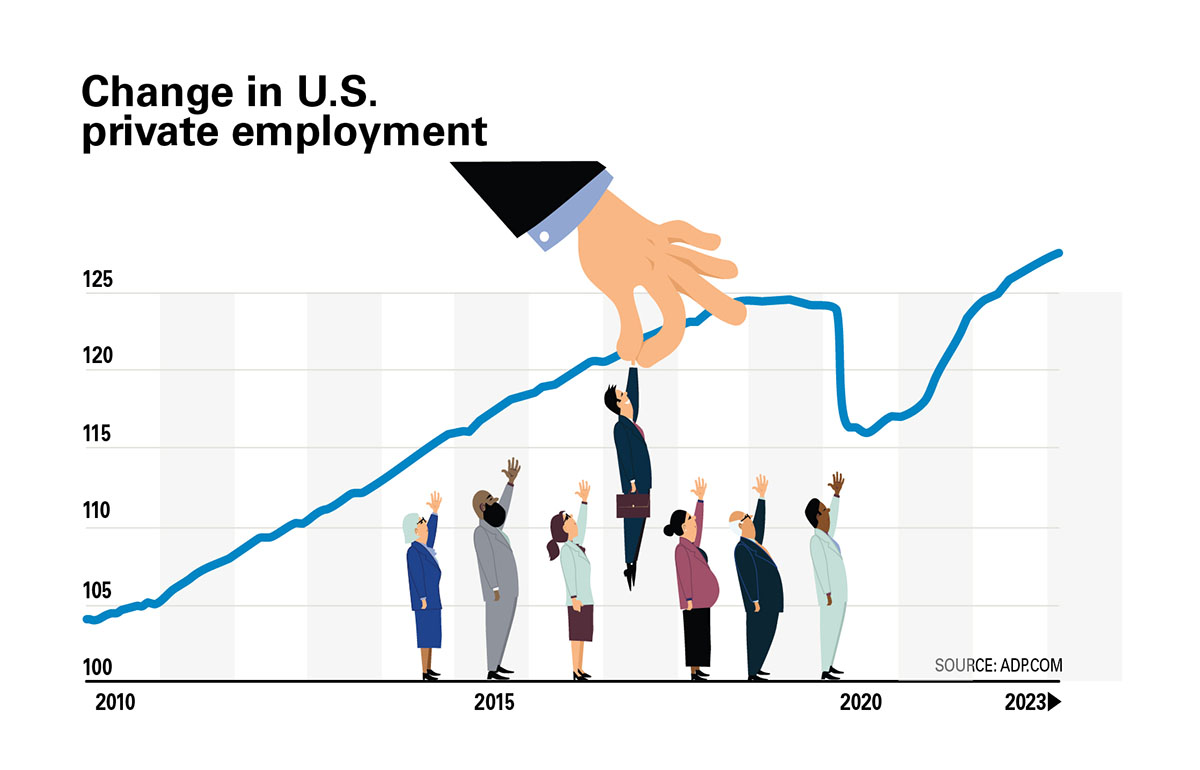

“Thinking back to different recessions, if job formation doesn’t crater, a soft landing is likely. And while we expect a drop in household formation, a recipe for a hard landing would be an economic event that causes massive doubling up or renters moving back in with their parents when their parents want desperately for them to move out,” he said.

Massive layoffs have grabbed headlines recently, but Pinnegar notes that so far these are mainly in the tech sector. According Layoffs.fyi, a website that has tracked tech layoffs since March 2020, 297 tech companies have laid off nearly 95,000 workers since the beginning of this year. At that rate, more than 900,000 jobs could be cut by 2024.

Since the tech sector expanded its footprint beyond traditional tech hubs as a result of remote work during the pandemic, more rental markets are now vulnerable to these mass layoffs. “Even so, the greatest impact on multifamily will be felt in tech-heavy markets that never really recovered from the pandemic, like San Francisco. For these markets, it will be a double whammy,” he said.

Power shift

Pinnegar doesn’t expect the Fed to reduce interest rates as quickly as it did in the 70s, “so over time everyone is going to feel the pain,” he said.

He also expects to see a shift in the power dynamic between employees and employers as job formation slows. Employees coming out of COVID had all the power, which led to employees working from home and to the Great Resignation when many people quit their jobs.

“Employers struggled to fill jobs and had to be flexible with remote work, but as the economy presents more challenges that stretch out through the rest of 2023 and into 2024, we will see a resurgence of our urban cores when employees are called back to the office.

“The pendulum will swing back to some people working in office and some at home, but still located close to the corporate headquarters. As a result, employers will look to centralization strategies—ways to transfer site level tasks and functions to a central location and control costs as much as possible,” he said.

Revolutionizing operations

As unescorted property tours become the norm, employees will be free to carry out administrative work for a number of apartment properties from a central location, providing a career path for people to move up from site level as they move up in the ranks of the industry, an unintended positive consequence of centralization, said Pinnegar.

Operators will continue to cut costs through the use of technology and AI will continue to be a factor with greater efficiencies as a result. “We’ll still need humans when something goes wrong because tech is great until it doesn’t work,” he said.

Despite the cyclical headwinds affecting multifamily, the interest rate hike that has pushed up mortgage rates is making renting more economical compared to homeownership than ever—a tailwind for the industry.

Meanwhile, slowing household formation and the increase in vacancy rates could spell a reprieve for renters from the massive rent increases during of the post covid environment. “In previous recessions, we saw renters going from special to special looking for the best rent deal and that’s something that could happen again,” he said.

The way forward

As the industry prepares to navigate the volatile year ahead, experts believe a preference toward rental housing will buoy apartment demand well into 2030, thanks in part to high mortgage rates that are pricing households out of homeownership.

And, despite troubling headwinds, multifamily offers relative stability and predictability for investors. “The asset class isn’t subject to the highs and lows of other sectors and will remain a bright spot in the commercial real estate universe. Distress will mainly be among newer players who are overleveraged,” said Pinnegar.

Savvy investors that have weathered recession storms in the past are sitting on plenty of dry powder looking for distress or the opportunity to team up with reliable seasoned developers that offer the chance to garner huge returns.

In the midst of uncertainty, one thing remains crystal clear—people need places to live and as long as they do, there will be opportunities for multifamily investors.

Author Wendy Broffman