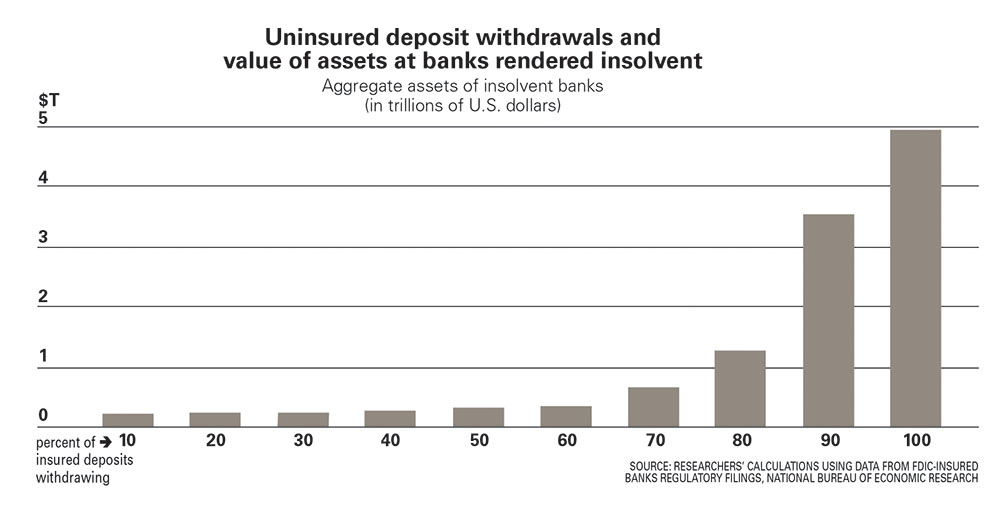

Banks have seen a lot of concerns over the last few months by depositors, investors and regulators. Multiple institutions were shuttered when it became clear that rising interest rates undermined the value of their assets. Depositors pulled their deposits, concerned about banks’ liquidity. That lead to insolvency and closures. A study suggested that increased monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve could shutter 186 banks.

But according to experts from rating agencies to long-experienced CRE professionals, the Fed doesn’t have to lift a single finger. A similar cycle might happen over commercial real estate loans.

According to Fitch Ratings, banks with less than $100 billion in assets—most—are “more susceptible to deteriorating commercial real estate (CRE) fundamentals than larger banks.”

Tightening to the point of failure

“The tight monetary environment has placed pressure on most CRE properties’ collateral values and transaction volumes while structural changes in demand for office space have adversely impacted occupancy for that asset class,” Fitch wrote. “These factors increase credit risk for banks that have CRE loan concentrations, and are expected to have an impact on asset quality in CRE loan portfolios of U.S. banks.”

According to the firm, banks are the largest lender to the office market with about $720 billion in loans. “Assuming a hypothetical stressed loss rate of 20 percent for these loans (about double the 9.8 percent average nine-quarter loss rate for CRE per the 2022 severely adverse DFAST), this results in about $145 billion of cumulative losses, or 8 percent of the sector’s $1.76 trillion of tangible common equity, which banks should be able to absorb over time as they work through their maturities and renewals,” they said.

But office isn’t the only trouble. “Like all sectors of the economy, CRE is under stress from higher rates, which cut into property cash flows and put downward pressure on the value of the properties themselves,” Brian Graham, partner and co-founder at Klaros Group, said. “On top of that, however, certain CRE sectors (by geography like central business districts in large cities and property type like office) are under extra stress resulting from shifts in behavior (work from home, more online shopping, decline of movie theatres, etc.). Conversely, some CRE sectors (like data centers and transportation warehouses) are experiencing tail winds.”

Multifamily, often considered relatively invulnerable because people need a place to live, offers another potential weakness because of the current pace of construction. The multifamily sector has been overbuilding, says Marcel Arsenault, CEO of Real Capital Solutions, which he thinks will lead to significantly higher vacancy rates than are currently the case.

Construction loans will face the need for refinancing, and many of them won’t be able to afford either the additional capital investment when loan-to-value ratios go from about 70 percent to 50 percent and rates are up multiple percentage points.

“Everything’s overpriced, Arsenault said. “If there’s a million units, whatever vacancy is today, I can promise it will be higher tomorrow. Why buy at a 6 percent vacancy if it’s going to 11 percent?”

In early March, CBRE forecast “a near-record 716,000 new multifamily housing units over the next two years” that will push the sector’s vacancy rate 4.6 percent to a peak of 5.2 percent by year-end. Arsenault, who’s been in real estate since the savings and loan crash in the 1980s reckons something more like a million units in progress and that refinancing rates could push many developers’ projects into unprofitability, which would lead to devalued construction loans.

Some banks have loaded up heavily on CRE loans. In its Q1 earnings release, for example, Bank OZK filings showed that out of $21.8 billion in outstanding loans, a full 39.3 percent were for construction and land development and non-farm non-residential was 22.1 percent for a total 61.4 percent.

PacWest, which sold its CRE loan portfolio to Kennedy Wilson and its real estate lending arm to Roc Capital Holdings, had at the end of 2023 Q1 78 percent of its $25.7 billion loans and leases in real estate, much in commercial.

Western Alliance, another bank in potential danger, finished Q1 with 29.9 percent of loans held for investment being CRE or construction and land development, almost $15.6 billion total.

Complicating the picture is the lack of information on smaller banks. As Fitch wrote, “However, the majority of the CRE exposure is held on smaller bank balance sheets, which are not rated by Fitch, limiting our visibility into lender-level credit quality for the broader industry, which includes 4,700 FDIC-insured banks.”

Source Erik Sherman, GlobeSt