The theme of multifamily industry reports this year has centered around uncertainty, but seasoned apartment developers, investors and analysts believe the sector is well positioned to weather economic storms.

They call what some see as a slowdown simply a return to normal after 2021, which likely was the industry’s strongest year ever on record.

Multifamily is considered both a defensive and countercyclical investment play, historically outperforming during economic downturns.

And its recession-resistant reputation is not just anecdotal. Privately owned apartments have produced an average real annual return well above that of major stock market indices since 1987, according to Berkadia Research. Industry participants have been able to capitalize on opportunities during all market cycles, including slowdowns and corrections, so for investors who think a recession possible by year-end, multifamily is a relatively safe investment.

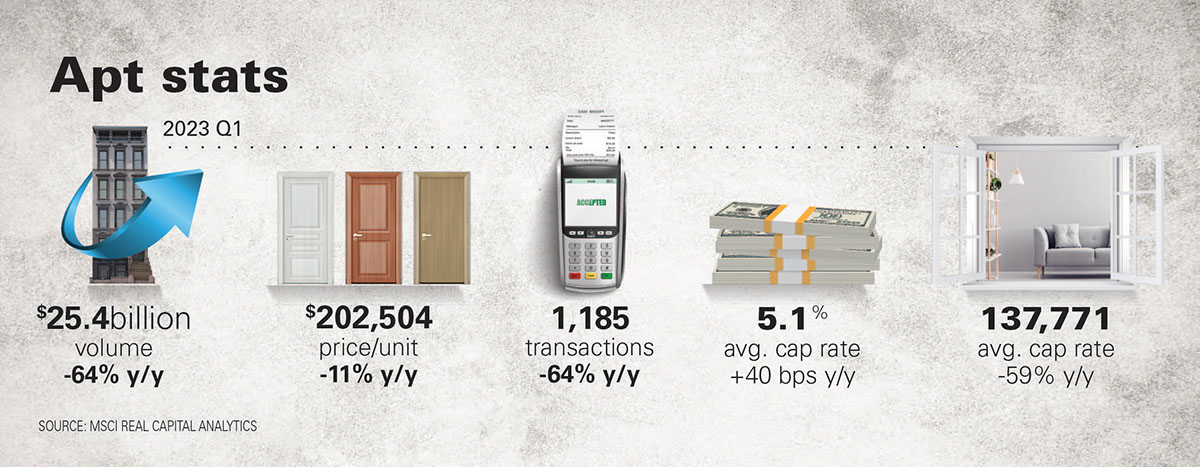

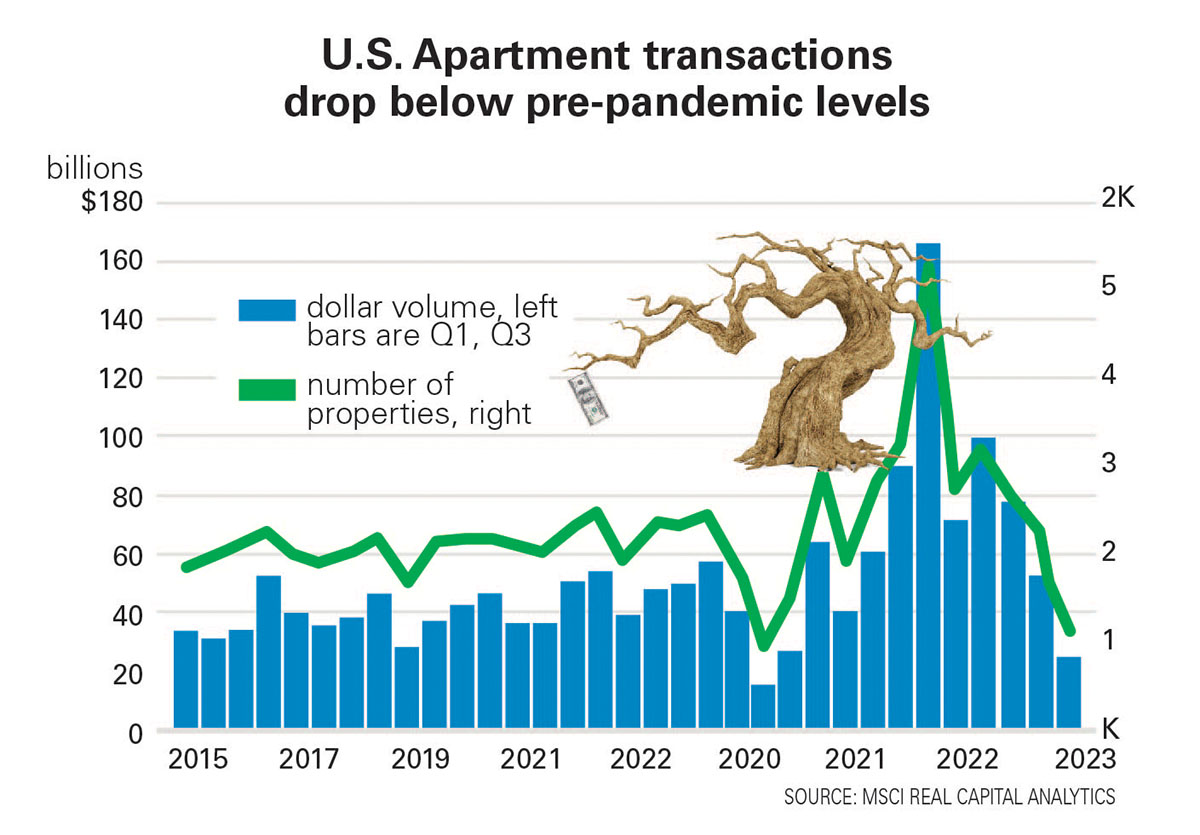

Now, halfway through 2023, apartment transactions are at their lowest level since 2011, primarily due to high interest rates and mismatched buyer/seller pricing expectations, and the industry is in the midst of a deluge of product that will come online through 2024.

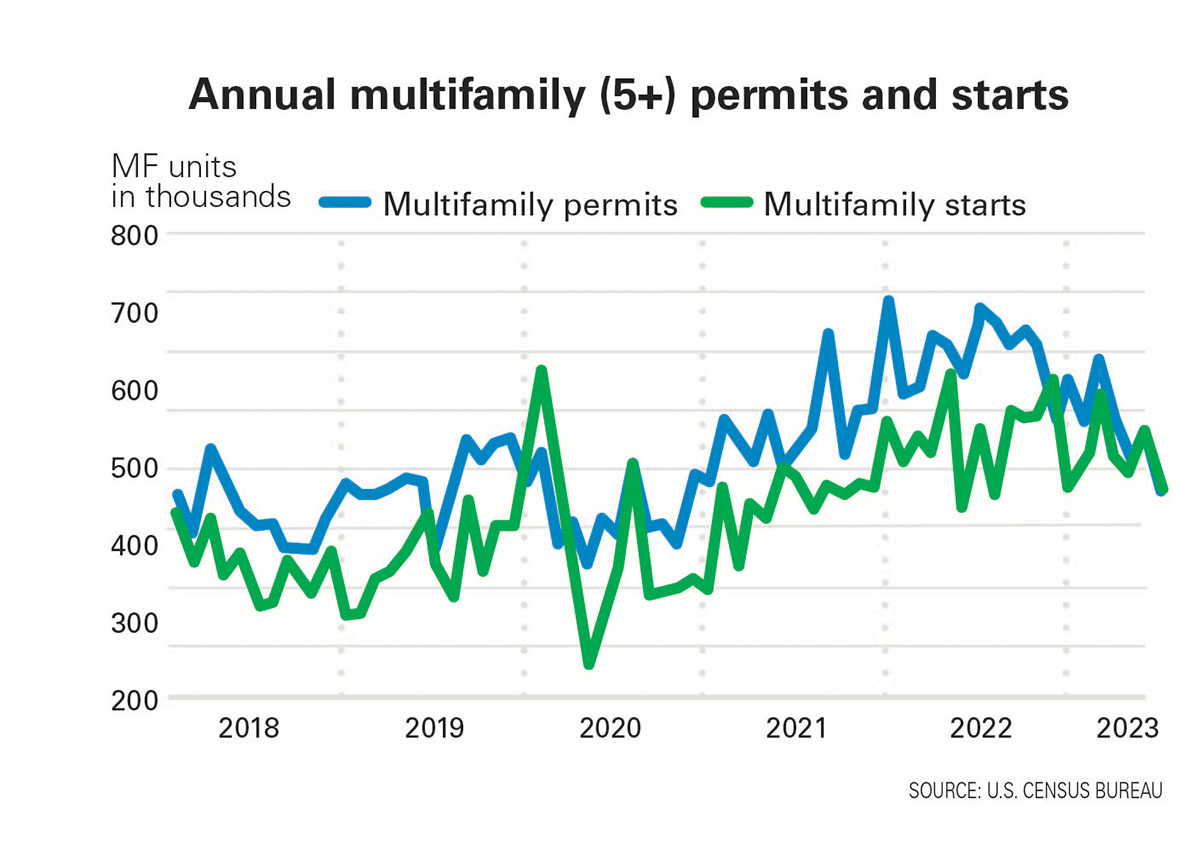

The latest numbers on multifamily construction starts from the U.S. Census Bureau target May 2023 as hitting a 36-year high at 58,500 units, up 41 percent from April, then revised the number downward afterward. The bureau collects building permits from cities and municipalities and surveys a small number of permit holders to estimate construction starts.

Jay Parsons, senior VP and chief economist for RealPage says these numbers raised a red flag for industry analysts.

“We’ve been pretty well aligned with census numbers historically, but in the past couple of years we’ve identified discrepancies. The Census Bureau is considered the public source for this type of information, so when we saw the May and June numbers, we looked around for supporting information,” he said.

By its own admission, the Census Bureau “does not have a large enough sample size to make state or local area estimates” on statistics.

But RealPage derives data by tracking construction project by project across the country, talking to developers, to municipalities and using satellite imaging and news articles to verify every individual project.

RealPage contacted Architects Trade Group that tracks multifamily billings for architecture firms. The group reported billings down for 11 straight months.

The Federal Reserve Senior Loan Officer Survey showed a dramatic pullback in construction lending and the National Multifamily Housing Council’s quarterly survey of multifamily developers and builders revealed a significant increase in developers reporting delays.

“We concluded the Census is playing catch up on starts that actually occurred in 2022,” said Parsons.

Future forecast

Based on this data, RealPage is betting that actual multifamily starts will drop more than 30 percent this year over last, with the drop-off accelerating in the second half of this year and peaking in the back end of 2023 through 2024.

There is a perfect storm of factors precipitating the drop-off, says Parsons.

“We are hearing of more stalled apartments projects since the great Financial Crisis of 2008 due to difficulty securing debt and/or equity financing,” he said.

Banks are being pressured by regulators to curtail lending and keep more cash on hand. Many lenders are already fully allocated in the multifamily sector.

“Most banks have a certain percentage of their loan portfolio aimed at construction and what they need to see is these projects complete and refinanced into permanent financing and that frees up capital for them to loan out for new projects,” said Parsons.

But concerns about the economy and worries that supply might surpass demand in the next couple of years also are factors that could lead to a pullback in bank lending, he said.

In this environment, with supply hitting a 30-year high and rent growth slowing, developers are required to have more equity than in the past, in an environment where people have less money to invest.

Parsons notes that only those with strong projects and lender relationships will prevail, but not at 2022 volumes.

“This suggests a material slowdown in completions by 2025 and the creation of opportunity for players with a longer-term outlook on the industry,” he said.

Construction delays, new influencers

While many projects won’t make it out of the ground this year and next, Parsons says it’s not because of the same issues that influenced delays in the past.

“What’s interesting is a couple of years ago it was the supply chain and labor market shortages. It was really clear in the previous NMHC surveys and from talking to folks that projects were taking longer to complete or start because they couldn’t get the materials or the labor, but that’s gotten better.

“And the thing about those issues is they delay a project, but the project still starts. It may take a bit longer, but it still happens. What’s happening now is there is a big increase in delays due to financing issues, and when that happens, that is an indefinite delay. It’s no longer ‘I have to wait until there are more windows in stock or until they can get them to the construction site.’ Now developers are waiting for capital to get freed up to actually start their projects and they don’t know if that’s going to be a month from now, a year from now or if that project dies on the vine, so it’s a much more significant factor,” he said.

He thinks supply will plateau at peak for about 12 months by the end of this year and then start to come down, but remain significant through 2024 and maybe even the beginning of 2025.

Buckets of deliveries

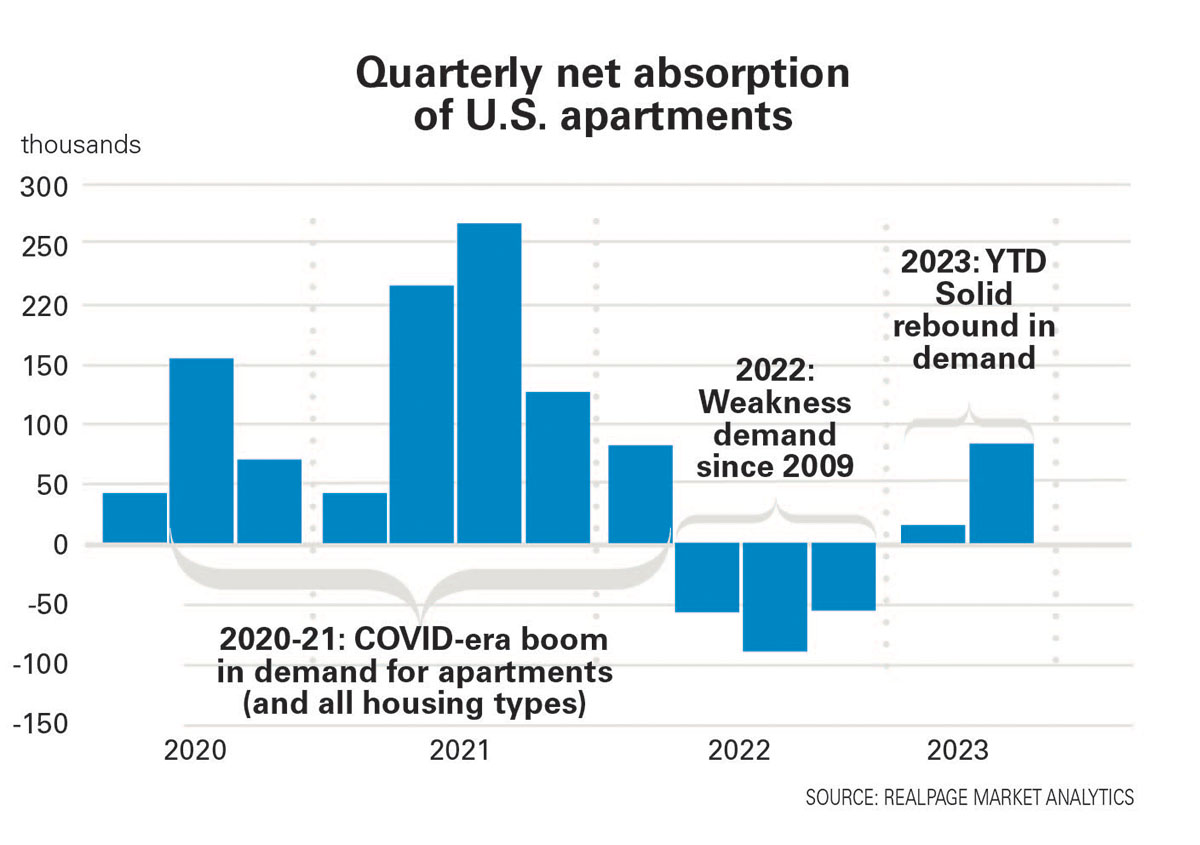

Parsons points to a number of contributing factors to the supply wave, including the pandemic that postponed projects breaking ground, the demographic variable and trend toward decoupling roommates.

“We also saw rapid income growth among the young adults who rent in market-rate apartments, particularly in the Class A space that caters to new construction. We got to a point early last year where we had the lowest vacancy level in decades. We were grossly undersupplied, so we need all this supply, it’s just going to be tough to absorb this much in a short period of time,” he said.

Real estate firm CBRE forecasts that even with this new supply, the industry still needs 230,000 units annually, or 2.3 million new units over next 10 years, to meet future demand.

The challenge, Parson’s said, is that supply is rarely delivered in smooth buckets that align with demand.

“Supply is volatile and arrives in cycles, so we go through a period where we are grossly undersupplied and we are going to be in a period for the next 18 months where there is likely to be more supply than demand.

“Long term it catches up, but getting 200,000 a year is much closer to the long-term average versus where we are right now, which can be three times that number. One concern is that by the time we get to 2025, early 2026, we could be undersupplied again,” Parsons said.

Affordability crisis—possible tailwind

Part of the challenge for the industry is that most of the supply that gets built tends to be luxury apartments catering to renters who are making six figure incomes.

More demand is coming from renters at the middle and lower price points, but due to the cost of land and labor and approval processes, that product is much harder to build, leaving developers dependent on subsidy programs to deliver product that rent at those price points.

“We are seeing more of that thankfully, but it’s going to be a challenge now and in the future to build for middle- and lower-income renters. Eventually Class A properties become Class Bs, and when you pull higher income renters out of a Class B property into a new lease-up, Class B availability opens up.

“So that’s a win, but there is still a huge chunk of the population that can’t afford to rent any market-rate apartment, even a B or C, so the only way to meet demand for that population is through programs like low-income housing tax credits, where you subsidize construction, and voucher programs,” said Parsons, noting that affordability is a complicated topic with two competing realities.

“One is the severe shortage of housing for low-income households, there is no doubt about that, but when you look at market-rate housing, it’s generally those paying a low 20 percent of income toward rent, so not as much of an issue as it is for those who can’t afford the space at all,” he said.

Secondly, according to news articles, consumer prices could actually be falling in some areas and wages are still going up, which could create a positive story for affordability, he said.

“I don’t want to overly bank on that one, but I don’t think it is quite as much of a headwind as it is being portrayed to be, specific to market-rate housing,” said Parsons.

Demand and demographics are the other tailwinds, including growth in the younger population and a large boomer demographic. Even a small percentage of those groups downsizing into a rental for some flexibility has an impact on the market, because their population is so large.

Meanwhile, the cost of homeownership continues to be significantly higher than renting, meaning fewer renters will be moving out to buy a home.

“Home costs have gone up faster since COVID. There’s little inventory coming on the market and much of what’s selling in the single-family home arena is new construction in the middle and upper price points, but over time it will get easier, we’re just are not there yet,” he said.

As the apartment market settles back into pre-pandemic levels of rent growth and occupancy, supply is obviously a big headwind over the next 18 months. Every existing apartment is competing with new construction for renters at the top of the market. Parsons thinks long term that’s a good thing because the nation needs more housing, but it’s challenging for apartment operators in the short term.

The good news is in the headlines reporting that job growth exceeds expectations, but there is still a risk that if the job market slows down, if wage growth comes down, the equation could become challenging when coupled with recent supply, said Parsons.

More good news is that inflation is easing, but food costs in particular remain a concern.

“Food is something everyone pays for, no matter what wage bracket they are in. Food prices affect everyone, not only our spending power, but our consumer psyche and how we feel about the economy and the future,” he said.

Author Wendy Broffman