The effect of years of remote learning during the pandemic is gumming up workplaces around the country. It is one reason professional service jobs are going unfilled and goods aren’t making it to market. It also helps explain why national productivity has fallen for the past five quarters, the longest contraction since at least 1948, according to the U.S. Labor Department.

The shortcomings run the gamut from general knowledge, including how to make change at a register, to soft skills such as working with others. Employers are spending more time and resources searching for candidates and often lowering expectations when they hire. Then they are spending millions to fix new employees’ lack of basic skills.

Talent First, a business-led workforce-development organization in Grand Rapids, Mich., is encouraging employers to stop trying to hire based on skill. Instead, hiring managers should look for a willingness to learn, said President Kevin Stotts.

“Employers are saying, ‘We’re just trying to find some people who could fog the mirror,’” Stotts said.

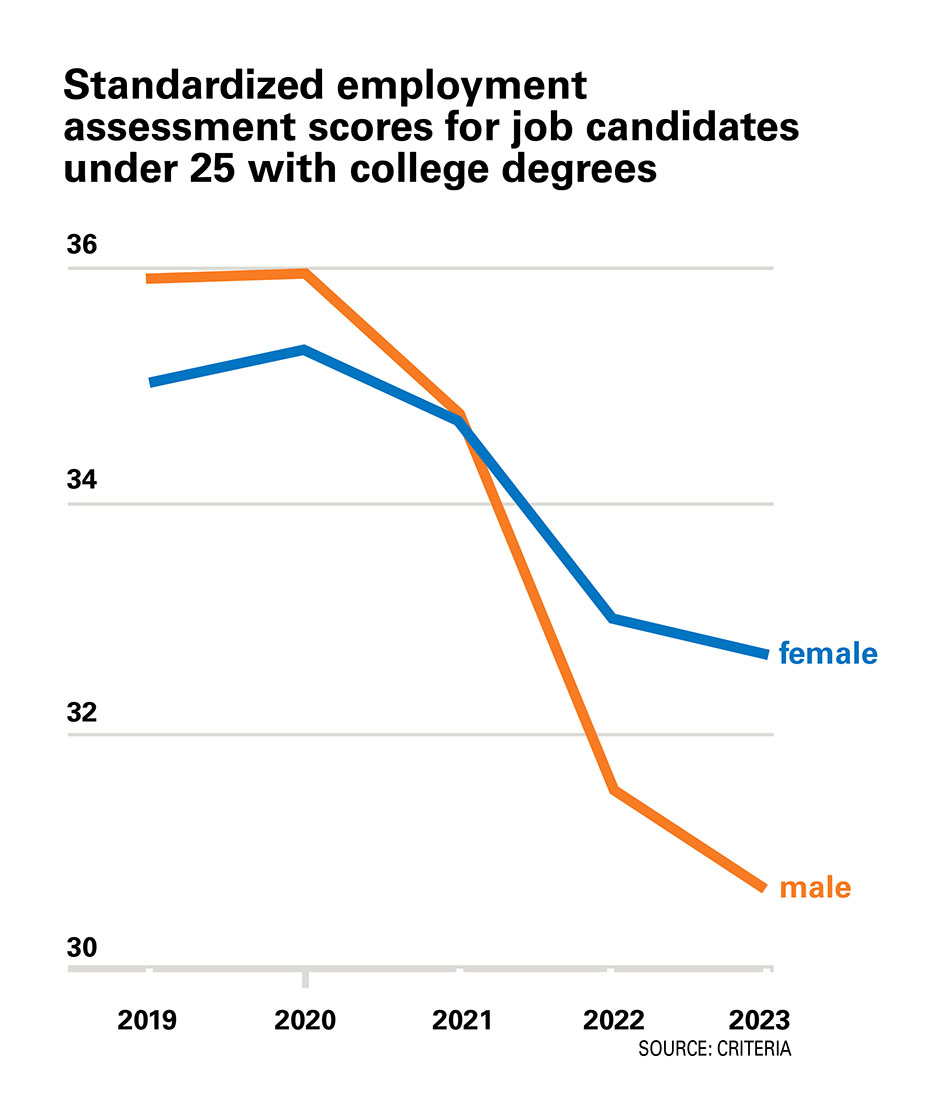

Since 2020, when the pandemic began and remote learning moved students out of schools and into virtual classrooms, the pass rates on national certifications and assessment exams taken by engineers, office workers, soldiers and nurses have all fallen.

Among the approximately 40,000 candidates taking the Fundamentals of Engineering exam for work as professional engineers, scores fell by about 10 percent during the pandemic, said David Cox, CEO of the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying.

That means fewer engineers on the job and a lower degree of competency among those who make it, he said.

The sharpest declines in scores came on questions measuring the most specialized knowledge. Structural engineers failed to answer questions about the use of trusses in the construction of bridges and roadways, Cox said.

“These are areas that are very much involved in public safety,” he said.

Students in elementary and middle schools across the nation fell behind by an average of about four months during the pandemic after classes switched to remote learning in 2020 and stayed that way in some cases through 2021. On national standardized tests, the scores of fourth- and eighth-graders fell to 30-year lows.

Cindy Neal, owner of Express Employment Professionals in Peoria, Ill., places about 1,500 people in jobs every year. Since the pandemic, she has seen sharp declines in the behavior of job applicants as well as their performance on employment exams.

The company has long offered courses for people to gain new skills such as QuickBooks. This spring they added new courses to help prospective workers with soft skills. Some of the chapters taught include taking initiative, personal productivity, cellphone etiquette, workplace hygiene, dressing appropriately for work and handling conflict with co-workers.

“This stuff used to be taught in schools,” Neal said. “Now people have to be told not to bring their kids to work.”

Results on the 15-minute employment exam the company administers to clients when they walk in the door are also declining.

Tasks on the quiz include recognizing misspellings in words like “availability,” “repetition” and “privilege,” and math questions such as: “If you were asked to load 225 boxes onto a truck and the boxes are crated, with each crate containing nine boxes, how many crates would you need to load?”

The scores in math and spelling are the worst she’s seen in 30 years, she said, adding, “I’m really concerned by the product that’s coming out of the school system currently.”

Excerpt Douglas Belkin, Ben Chapman, Ben Kesling, wsj.com