The pandemic created a number of anomalies in the rental market that will take some time to normalize, not the least of which is in market rents. While more than 35 percent of Americans rent their home, according to the latest Bureau of Labor Statistics’ consumer price index data for shelter and rent, renting has become more expensive than ever over the past few years.

Inflation, a lack of inventory and a shifting workforce sent market rents in the U.S. skyrocketing, finally hitting an annual peak in February 2022 and slowly floating back to earth ever since.

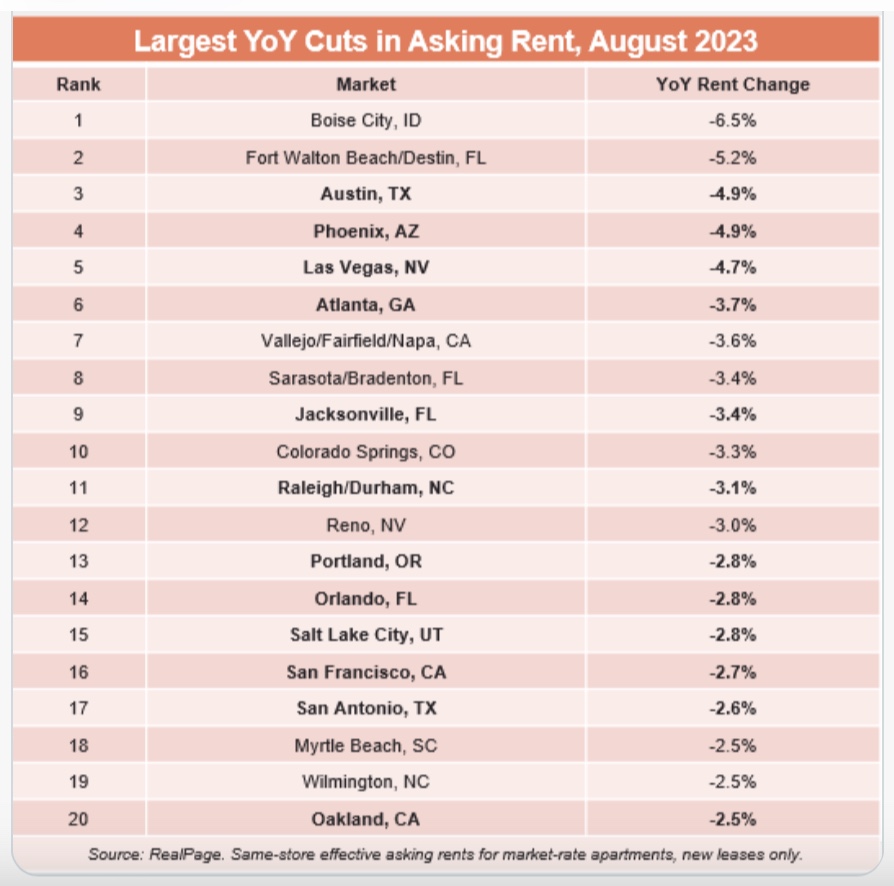

The metros seeing the largest corrections in market rents today are the soft-demand West Coast markets, where 64 percent of metros are showing rent cuts, and the Sunbelt markets with both high demand and high supply, where 45 percent are posting negative rents, explained RealPage rental housing economist Jay Parsons.

Rent cuts are deepest in Phoenix, Austin and Las Vegas, with all three nearing negative five percent on an annualized basis as demand lags supply. Others include Atlanta, Jacksonville, Raleigh/Durham, Orlando, Salt Lake City and Nashville.

Parsons says the same pattern is playing out in hot tertiary markets like Boise, Sarasota, Colorado Springs and Wilmington, NC, all of which experienced strong demand and new construction.

While analysts predicted West Coast market rents would hold up because COVID slowed construction there, the factor of diminished supply has only had a positive effect in specific submarkets like downtown Seattle and downtown Los Angeles and certain parts of Silicon Valley, said Parsons.

Meanwhile, markets with meager construction are still seeing rent growth. The Midwest and the Northeast, where demand has been steady but supply less abundant, are experiencing rent growth at more normalized rates.

But, among the top 150 largest U.S. metros covered by RealPage, those seeing the most rent increases are mostly small markets with stagnating construction. Most notable on the list are college towns. Campuses closed during the pandemic and construction screeched to a halt. “Schools have reopened and demand rebounded, but since it takes a couple of years to finish a project, very little is hitting the market in 2023-24,” said Parsons.

Good news for markets most impacted by high supply and falling rents is that cautious lending is challenging developers’ ability to procure construction loans and equity to start new projects. Multifamily deliveries are expected to slow in early 2025 and drop off in the latter part of the year, predicts Marcus & Millichap.

Meanwhile long-term developers and investors like Arn Cenedella, founder of Greenville South Carolina-based Spark Investment Group see this current cycle as a needed cooling period following almost a decade of boom years, setting the stage for more growth in the future.

“I’m still a buyer. I don’t try and time the market. I look to buy quality assets in growth markets and have faith that over the next five to 10 years, my investors and I will be rewarded,” said Cenedella.