In a growing number of places, apartment properties are likely to have to reduce the carbon they contribute to the atmosphere.

Cities, towns and entire states across the U.S. have declared war on climate change— and it is going to be brutal.

A few years ago, developers could install a few solar panels on top of an apartment building to signal to renters and local officials that the apartment was more or less “sustainably designed” and win some grant money from a local utility.

Ambitious “green” developers could have their projects certified for their energy efficiency, sometimes earning them more generous financing. Many improvements—especially those that saved water—paid of themselves rapidly, even without help from green building programs.

Times have changed

Forty cities from Reno, Nevada, to Denver, Colo., have created “building performance standards” to “de-carbonize”—cutting the amount of carbon that apartment buildings release into the atmosphere, according to the Institute for Market Transformation, based in Washington, D.C.

The most aggressive cities—like Boston and New York—threaten owners with heavy fines.

“This is much more aggressive and much more challenging, particularly for private building owners,” said Paula Cino, vice president for construction, development, land use and counsel for the National Multifamily Housing Council, based in Washington, D.C.

To comply, owners in these jurisdictions will eventually have to reduce emissions from many large, apartment properties to net-zero.

“Decarbonization, or deep energy retrofits, are not going to pay for themselves in energy cost savings—despite the many benefits of retrofits,” said Christina McPike, director of energy and sustainability for WinnDevelopment, an affordable housing developer based in Boston.

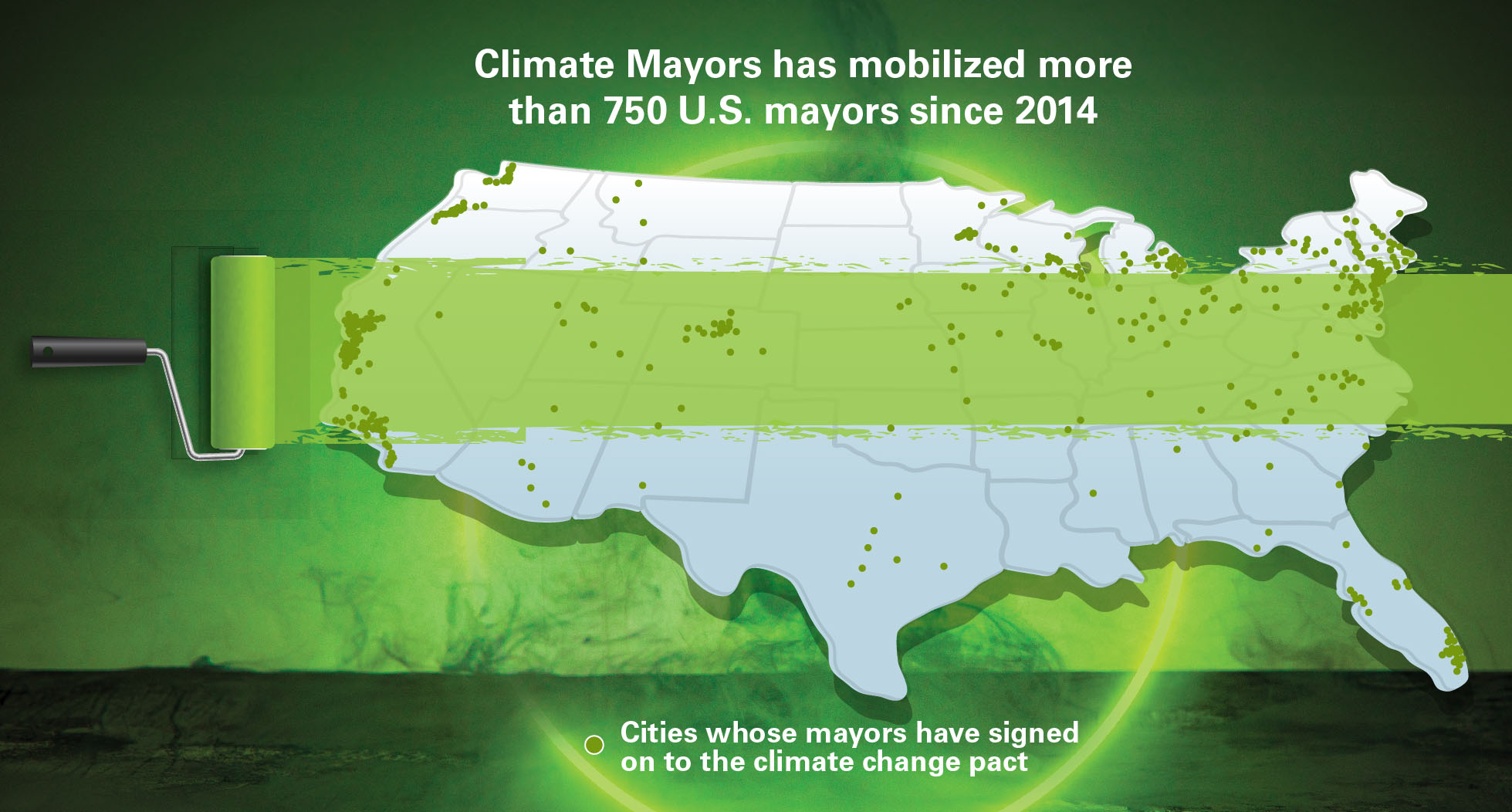

750+ towns commit to reduce carbon

New York City and Boston are among the first jurisdictions to demand that owners cut the carbon produced at existing apartment properties. But they are unlikely to be the last.

The mayors of more than 750 cities and towns across the U.S. have committed to fight climate change through the “Climate Mayors” network.

These cities and towns have accepted the basic premise that human activity is causing the average temperature of the planet to rise, causing extreme weather from flooding to wildfires.

More than 500 of the towns on the Climate Mayors list have explicitly committed to the goals set by the Paris Climate Agreement, which the U.S. rejoined in 2021. The international treaty calls on hundreds of nations to keep the world average temperature from rising more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit from pre-industrial levels. Those towns include a huge range of places, like Anchorage, Alaska; Jackson, Miss., and Bethlehem, Penn.

To accomplish those goals, jurisdictions will have to release much less carbon into the atmosphere than they do today. The first step for cities like New York was to collect information on the carbon produced in their jurisdictions. Owners of large apartment properties began to “benchmark” their utility use, reporting annually how much energy was used at their properties.

“Having the data opened everybody’s eyes,” said Breana Wheeler, director of operations – U.S. for BRE Group, working in the organization’s San Francisco offices. BRE manages the BREEAM certification standard for low-carbon real estate.

“For cities and jurisdictions that are looking to reduce their carbon, for many of them buildings are their biggest source of carbon emissions,” said Wheeler. “If they’re going to act on climate change, they need to go there.”

Potential buyers and decarbonization

It’s not just bureaucrats in your local city government that are pushing property owners and developers to decarbonize.

To please shareholders interested in sustainable investments, leading real estate investment trusts (REITs) like AIMCO and AvalonBay Communities have promised to reduce the amount of greenhouse gas emissions created by their activities.

Federal regulators at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission intend to hold these companies to their promises. A rule proposed in March 2022 would formalize reporting requirements for companies that promise to reduce their carbon. The SEC has delayed again and again its release of the final version of the rule. But companies are already taking action.

“Potential SEC fines loom over the publicly-owned real estate industry,” said Allison Kirby, associate director of ESG and sustainability for Cushman and Wakefield. “Property owners are preparing by ensuring energy data is being collected at the property level and that data issues are being addressed.”

These firms are major buyers of real estate. Many property owners now consider decarbonization as they plan to sell property.

Potential buyers who have made climate commitments may pass on the chance to buy an inefficient property—particularly in jurisdictions that have begun to punish properties that produce too much carbon. That could result in lower prices—what BREEAM’s Wheeler calls the “brown discount.”

The growing focus on carbon could also result in higher prices for properties that create less carbon.

“ESG is a value-add strategy,” says Justin Gronlie, managing director at Harrison Street, a private equity fund manager based in Chicago. “The more we know about the changing regulatory landscape, the climate risk landscape, and value-add building initiatives, the more we can position our assets to demand a premium value in the future marketplace.”

Institutions push to decarbonize

Institutional investors in real estate—from pensions funds to sovereign wealth funds— have also made a web of promises to their stakeholders to reduce the carbon produced by their investments.

As a result, apartments developers who partner with foreign equity investors from the European Union will have to report on the carbon produced at their properties to comply with Europe’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR).

“The other night I couldn’t fall asleep because I was thinking about SFDR,” says Anne Peck, vice president and head of environment, social, governance and resiliency at TA Realty, an owner and manager of real estate including apartments based in Boston. “I’m not a European company, just I have European investors. I’m just trying to figure out how to report.”

Other equity partners may have to create other reports to please their own stakeholders.

“GRESB, the global ESG benchmark for the real estate industry, and the Climate Disclosure Project (CDP), have become staple annual reporting processes for many of our clients,” says Kirby.

Apartment properties that can prove that they produce less carbon may also be able to raise capital at relatively low interest rates by issuing “green bonds” to investors who are interested in low-carbon investments.

Elme Communities, the Washington, D.C.-based apartment company formerly known as Washington REIT, raised $350 million by issuing green bonds backed by five apartment properties that had earned certifications for their sustainable design—includes four properties that had earned BREEAM certifications for produce low amount of greenhouse gases and a fifth property that earned a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design certification.

Some renters and sustainability

A few renters are willing to pay slightly more to live in a building that is not damaging to the environment.

About half (50 percent) of the renters at properties managed by Elme Communities prefer living in sustainably developed communities that have earned certifications like LEED or Fitwel.

“It’s difficult to measure the level this impacts their decision to live there,” said Eric Tilden, senior director of ESG for Elme Communities. “Cost and location tend to be primary decision makers, then amenities and then finally sustainability.”

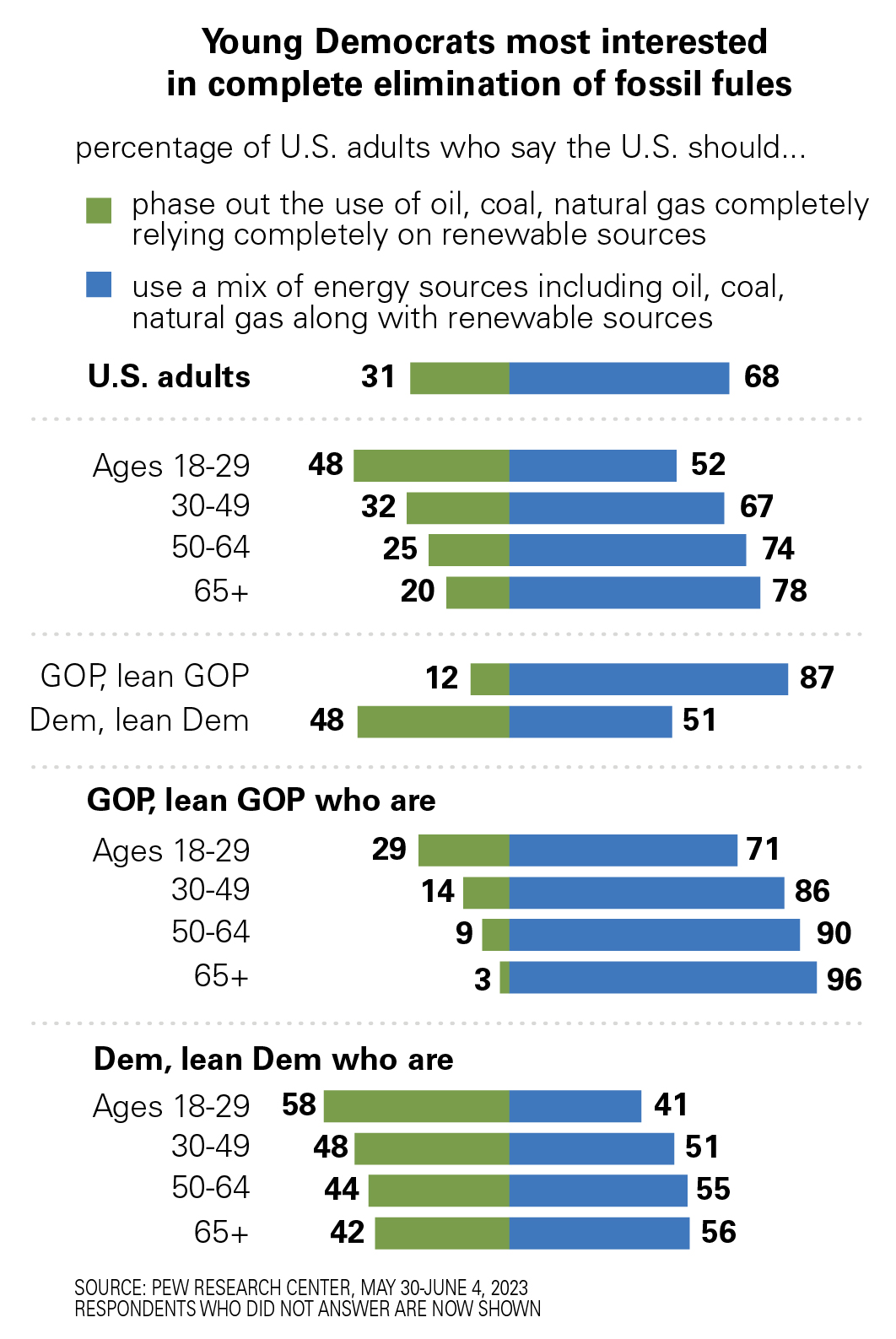

Sustainably might become more important, however, as more young people become old enough to form their own households.

“In a recent Pew survey, 37 percent of Generation Z said that addressing climate change was their top concern,” says Kirby. “As the multifamily market undergoes a demographic transition, Generation Z is emerging as the primary renter base as millennials transition to homeownership.”

The deadline is coming in NYC

Starting in calendar year 2024, apartment buildings in New York City that are larger than 25,000 sq. ft. will have to limit the amount of energy used per sq. ft. or pay a significant amount of fines.

Buildings heated by electrical systems like heat pumps will be able to use more energy per square foot without getting fined than buildings heated by gas or oil boilers.

“It’s possible to interpret the law as requiring apartment buildings to change from being heated with fossil fuels to being heated by electricity,” says Ariel Aufgang, principal at Aufgang Architects, based in New York City.

New York City first began to require apartment properties to benchmark their utility use in Local Law 84, passed in 2013. New York’s benchmarking rules suddenly grew teeth when the New York City Council passed its Local Law 97.

The rules will get tougher over time. All the buildings covered by the law must reduce their greenhouse gas emissions to zero beginning in 2050.

For buildings that need to replace a heating system that burns oil or gas with an electric system, it may be too late to avoid a fine.

“Even two years ago I would have asked is it too late. Getting anything done in New York City takes time,” says YuhTyng Patka, partner at Adler & Stachenfeld, a law firm based in New York City focused on commercial real estate.

Companies like CarbonQuest, a property technology firm, are working with owners to provide a quicker fix. CarbonQuest makes a system that removes carbon from the smoke from building chimneys.

Local experts estimate that between 3,000 and 5,000 buildings in NYC will face fines from Local Law 97 in 2024. That could rise to between 25,000 and 30,000 buildings in 2030.

“Decarbonization has become a more pervasive term,” said Brian Asparro, chief operating officer for CarbonQuest, with offices in New York City, though the company expects to do business across the U.S.

“New York with its law has created a catalytic event,” said Asparro. “Boston, Washington D.C., Denver, Bekeley, Calif.—they all have similar programs. It is a matter of time before they spread.”

WinnDevelopment plans for zero carbon

Owners of existing large apartment properties in Boston will have to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions all the way to net zero by 2050, to avoid fines set by the city’s Building Emissions Reduction and Disclosure Ordinance (BERDO).

Just as in New York City, the regulation in Boston started with a benchmarking ordinance.

“We’ve been required to report whole building energy data to the city for nearly ten years,” said WinnDevelopment’s McPike.

In 2022, Boston’s lawmakers added teeth to the benchmarking law.

The new law set limits on how much CO2 buildings can emit per sq. ft., based in their type, starting in 2025 and squeezing towards net zero by 2050. Buildings that give off too much CO2 must pay fines.

The rules will effectively require buildings heated by fossil fuels to replace their systems to avoid getting fined.

“You could insulate your building and you could cover every inch of the roof and vertical wall with solar panels,” says McPike. “So long as you’re still heating and making hot water using natural gas—which is the bulk of the portfolio—you won’t comply.”

Winn is already strategizing to switch out fossil-fuel burning systems that heat many of the roughly 7,000 apartments it manages in Boston.

“The vast majority of them will need to be retrofitted,” said McPike. Boston, unlike New York, has not exempted affordable housing from its decarbonization rules. Some of these renovations may have to wait until the buildings are ready to be recapitalized with a new round of financing from low-income housing tax credits, or other financing.

“There will be some building owners that I expect will need to request what’s called a hardship compliance plan,” said McPike.

These renovations are likely to be complicated.

The apartment stock in cities like New York and Boston include many buildings more than 100 years old, with extremely hot steam heat from gas or oil boilers to compensate for leaky walls with patchy insulation. Electric heating systems like heat pumps never get as hot as steam—so these old buildings will require an improved building envelop.

Conventional heat pumps may also be impractical for older buildings because of all the new pipes required to carry refrigerant to the heat pumps in each apartment. Winn is considering a new kind of heat pump system that would heat water in a central location that can be sent to the apartments using existing pipes.

“I’m working with a couple of young, brave engineers who were cold calling companies trying to learn how the system works—and if it will work,” says McPike.

Author Bendix Anderson