Investors are finally starting to take advantage of distress in the multifamily sector, even though the huge wave of distress pundits predicted last year failed to materialize.

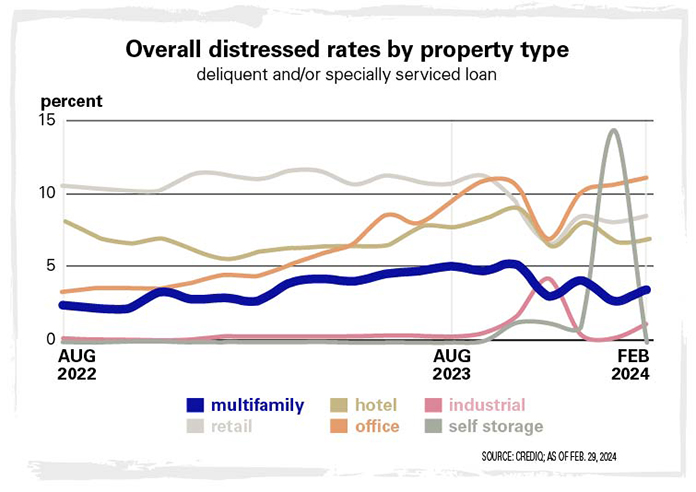

In February, multifamily distress hit its highest level in 18 months, increasing by 80 basis points over the previous month, according to CRED iQ, which tracks and analyzes data and valuations of more than $2 trillion in commercial real estate (CRE).

While the level of multifamily loans past due or on non-accruing status is still below long-term averages, and well below peak levels, credit rating agency Fitch Ratings expects distress will be prevalent among certain multifamily loans this year.

Especially at risk are merchant builders struggling to lease up properties that are now valued below underwriting, as are rent-stabilized properties reliant on overly optimistic rent increase projections, or those in submarkets with elevated vacancy rates and excess supply. Many are in the Sunbelt states of Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and the Carolinas, according to Fitch.

Especially at risk are merchant builders struggling to lease up properties that are now valued below underwriting, as are rent-stabilized properties reliant on overly optimistic rent increase projections, or those in submarkets with elevated vacancy rates and excess supply. Many are in the Sunbelt states of Texas, Florida, Tennessee, and the Carolinas, according to Fitch.

After being sidelined for years, while building up a cache of dry powder, opportunistic investors are hoping the time is finally here to capitalize on the situation. This includes providing “gap capital” for owners of properties in need of extra funds to pay off maturing mortgages or buying the properties outright from owners forced to sell.

Arizona investment company Neighborhood Ventures sent out a press release this month looking for investors with a minimum of $50,000 to join a crowdfunded REIT that plans to acquire five to 10 distressed multifamily properties there.

Another group, Florida-based NUVO Capital Partners, has come up with a strategy to acquire off-market and premarket distressed properties through deals that enable the sellers to participate and recoup at least some of their initial investment.

The question is whether distress hunters will succeed in finding the opportunities they are looking for. So far, relatively few distressed apartment properties have become available for sale, since banks and sellers are choosing to avoid defaults by negotiating loan extensions.

Yardi Matrix Director of U.S. Research Paul Fiorilla thinks as long as the economy remains relatively strong, much of the distress in the multifamily sector will be mitigated.

But with a wave of debt coming due, rents flat, insurance elevated and supply and interest rates not seen at such high levels for years, tension is building in the apartment sector.

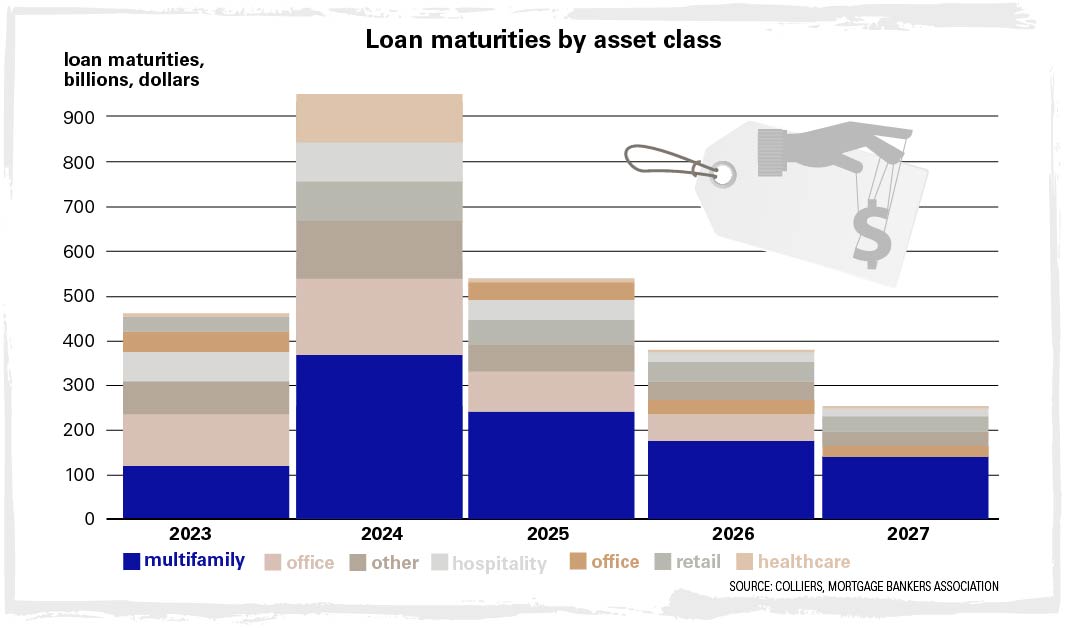

According to the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA), nearly $2.7 trillion of debt is maturing by 2027. But the lack of transactions coupled with built-in extension options and lender and servicer flexibility has meant that many CRE loans set to mature in 2023 were extended or modified to mature in future years, pushing the amount of CRE mortgages maturing in 2024 alone from $659 billion to $929 billion, said Jamie Woodwell, VP and head of commercial real estate research at MBA.

Roughly $1 trillion of the debt maturing by 2027 is associated with multifamily properties. For context, $75 billion matured in 2021, the highest amount on record, yet each year through 2027 looks to surpass that record, said Woodwell.

Roughly $1 trillion of the debt maturing by 2027 is associated with multifamily properties. For context, $75 billion matured in 2021, the highest amount on record, yet each year through 2027 looks to surpass that record, said Woodwell.

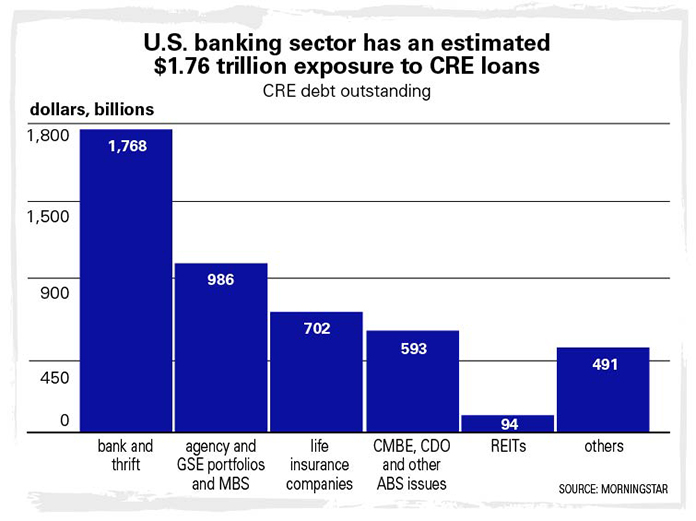

But Fiorilla thinks that while multifamily loan defaults could reach 10 percent of the $1 trillion in maturing loans, the actual losses suffered will be smaller once equity holders absorb the losses. The impact on the banking system also will be relatively small. The industry will see distress, but not another Great Financial Crisis (GFC)-type situation, he said.

“Small banks with exposure to real estate might suffer problems and some may even go out of business. But banks still don’t want to own property, so if owners want to hold on to the properties, banks will work with them as long as the property is performing. There’s money out there looking for distress, and it just can’t get spent,” said Fiorilla.

Stephen Buschbom, research director at data and analytic provider Trepp, thinks multifamily is in for some rough times over the next few years. He sees a parallel to the GFC of 2008 in terms of the level of uncertainty in the sector and extending loan maturities further into the future.

Stephen Buschbom, research director at data and analytic provider Trepp, thinks multifamily is in for some rough times over the next few years. He sees a parallel to the GFC of 2008 in terms of the level of uncertainty in the sector and extending loan maturities further into the future.

“But the situation heading into 2008 was very much an over-leveraged underwriting, credit-type problem, where today it’s rate-centric with much more disciplined underwriting. The overestimated underwriting is only on the fringes of the market,” he said.

Even so, rates remain at a 23-year high because the Federal Reserve is reluctant to lower them as long as the danger of inflation remains. Most pundits expect the Fed won’t cut rates until the latter half of 2024.

“There’s still so much cash in the system as a result of quantitative easing between 2009 and 2015 that getting that excess cash out of the system could be painful,” said Jim Young, senior managing director at the central Texas location of CRE investment firm Newmark.

Looking at loan maturities by lender type in Yardi Matrix’s database, the largest volume through the end of 2025 will come from the GSEs with $47.4 billion, followed by $46.5 billion from banks and $33.3 billion from debt funds. Because GSE loans tend to be permanent with longer terms, only 7.4 percent are maturing through 2025, compared to 47.8 percent of debt funds and 24.8 percent of bank loans.

Market-level data isn’t a great predictor of delinquency rates, because loan defaults tend to be property specific, according to Yardi. Most high-supply markets also have strong apartment demand, but large numbers of deliveries can extend lease-up time for new properties and increase concessions throughout the market and potentially cause stress.

Some highly leveraged investors who bought at the market peak are running out of time and may be forced to sell.

“We could be seeing the seeds of opportunity, but any real estate that can pay its way is unlikely to be fire-sold,” said Richard Barkham, global chief economist at CB Richard Ellis. He thinks investment opportunities will exist among poorer quality assets with leasing risk in tertiary locations, or even some newly developed assets with high vacancy rates.

“I would look at newer product struggling to lease up that kicked off in 2020 and 2021. I don’t know if those will be available to small investors, because that product will be larger and high-grade, but that’s where I think the stress is going to hit and those assets will provide opportunities this year for people with the right plan and the right perspective—particularly a long-term perspective,” said Barkham.

The right stuff

Brian Underdahl, chief analytics officer at NUVO Capital thinks his company has both the right perspective and the right plan to successfully navigate the stream of distressed multifamily assets that are beginning to bob to the surface.

He launched the company last year with partners Stuart Keller and Lenny Pisano. Each partner has decades of experience in various aspects of the multifamily sector. Although the partners have been value-added players in the past, they took a conservative approach when interest rates were low and, in most cases, remained on the sidelines.

“We had a pretty strict investment committee process and in that five-year period only invested in two deals. I’m happy to say they’re doing well,” said Underdahl, who managed a fund that invested passively in multifamily syndicators for six years prior to launching NUVO.

“That’s where our whole strategy stemmed from. I met with close to 600 sponsors in my time managing the fund and know many of them personally. I’ve underwritten an awful lot of their deals and when rates started going up in 2022, we realized that a whole lot of the deals that fortunately we did not invest in were going to be in real trouble,” he said.

When Underdahl hooked up with Keller, who brings to the partnership 16 years of experience in multifamily asset management and operations, they hammered out a strategy of acquiring distressed assets and helping the sellers out in the process by returning some of their capital and then operating the properties longer term.

Solutions watch

The company targets newly developed or stabilized assets in the Sunbelt and Southeast that were originally purchased or built with floating rate bridge debt in 2020 and 2021. As interest rates went up, the floating rates went up alongside them and the money the owner set aside for Cap Ex, for redevelopment or development, had to be diverted to pay the debt service on the property, said Underdahl.

The properties never were able to achieve the higher rents planned for in the owner’s value-add strategy, and when interest rates rose and the owners were unable to execute their improvement plans, the value of the assets dropped below the price of purchase.

“That’s where we come in with a solution,” he said. “In most cases, we acquire the asset for the loan balance, then write in the sellers to our structure as a ‘hope note’ strategy, where they can recoup some of their initial investment by essentially investing alongside us in the new structure.”

The partners have been waiting for about two and a half years and thought opportunity would strike last year. “It’s taken a long time. There were a lot of workouts and a lot of extensions and restructurings and it just pushed everything into 2024. Everyone was counting on rate cuts to come in and save the day and that hasn’t happened,” said Underdahl.

Instead, they spent 2023 developing relationships with the institutions and family offices they plan to partner with, educating them on the anticipated opportunities.

When the music’s over

“Our thesis is finally playing out with the distress here. We have term sheets with family offices and institutions to programmatically deploy equity into this space over the next two years, although it’s hard to say how long these opportunities will last,” said Underdahl.

He thinks 2024 will be the peak of distress that will spill over into 2025.

“But we are still seeing sellers and lenders doing everything they can to extend the process, kick the can further down the road and just stay afloat,” he said.

Trepp’s Buschbom expects the market will reach the halfway mark this year, working through the distress. “We wrote about what we call the fear-greed index in The Rundown, our weekly podcast focused on the latest news in CRE,” he said.

“Fear was keeping a lot of money on the sidelines last year. The bid-ask spreads were wide and there wasn’t any transaction volume. Then, in December and January of 2024, we saw a flurry of activity and over $7 billion in CMBS issuance of conduit large loans and single-asset borrowers versus half of that the same time last year. We’re starting to transition to the greed phase where deals will materialize, but still at very large bid-ask spreads,” said Buschbom.

Yardi’s Fiorilla cautions distressed investors to remain mindful that multifamily is more properly operated as a long-term strategy. “If you do play the short-term strategy, you could get caught when the market turns, like in a game of musical chairs. You’re OK until the music stops and there are no more chairs,” he said.

NUVO Capital is finally under contract on its first deal in the Sunbelt with a price of $35 million—essentially the loan balance, said Underdahl.

“It’s our first acquisition with this structure. That’s what I mean by taking a while for all this to play out. We’ve underwritten about $6 billion of properties that fit this distress profile. We estimate there’s about $136 billion more that will surface over the next two years,” he said.