We were once a nation of builders—from the toll roads and canals of the early nineteenth century and the railroads of the second half of that busy century, to the construction of power, energy, and water systems that were the envy of the world. Even Stalin hired American engineers and planners to build hydroelectric plants and car and other large-scale factories, some planned and developed by people from Detroit.

As Stalin knew, infrastructure is one of the keys to imperial power. Ancient Rome, the imperial dynasties of China, the Mesoamerican empires, the Islamic empire of the Caliphs, the British Empire, and finally our own global imperium all rested on massive infrastructure projects.

In the United States, American ingenuity, usually private but with public assistance, built the world’s largest industrial economy. In the 1930s, we produced the Hoover Dam, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and countless bridges, roads, and other critical infrastructure. When the Second World War broke out, America had the capacity, in a remarkably short time, to become “the Arsenal of Democracy.” Historian Richard Overy notes that “the material explanation for victory” lay largely in America’s relentless productive capacity.

From success to failure: The decline of American infrastructure

Economic historian Robert Gordon has described the rapid economic growth in the period of the 1920s to the 1950s as “one of the greatest achievements in all of economic history.” Yet today, once again faced with a powerful, sustained challenge by powerful autocracies—China, Russia, and Iran—the West and America have allowed our productive capacity to deteriorate. As we saw in the pandemic, and now again after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. and the West struggle to produce industrial products, including those of a military nature, that could prove critical in containing the new version of the early 1940s “pact of steel.”

The more recent decline of the West’s productive capacity—China now boasts as much industrial export capacity as the U.S., Japan, and Germany combined—has many causes, including insufficient investment in basic productive infrastructure. Much of this can be traced to regulators, particularly on climate related issues, who have, among other things, raised energy costs and contributed to the undermining of the electrical grid both in the U.S. and Europe. Even our military technology is increasingly dependent on Chinese inputs, most ominously in submarines.

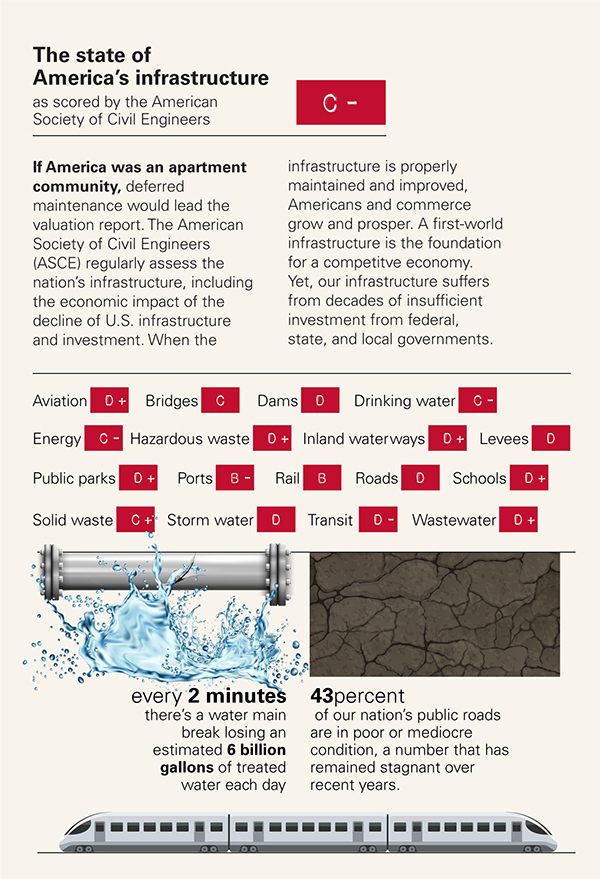

Today no one would look at America as a great example of infrastructure development, whether for transportation, energy, or the development of human capital. Once a leader, much of our infrastructure is nearly a century old. Every four years, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) produces its Report Card for America’s Infrastructure. Roads, ever more important in an era of rapid dispersion, have a grade of “D” even as 91 percent of all non-telework commutes are by car and nearly 45 percent of freight ton-miles are moved by truck.

Other critical transport infrastructure like inland waterways—which include rivers, the intracoastal waterway, and coastal shipping—get similarly low marks, as does aviation.

The recent collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore may be the latest example of our vulnerability, though evaluation of that accident is not complete. (The ASCE grade for bridges is “C,” better than the overall national grade for all infrastructure of “C-.”) China has long since passed the United States in its interstate standard highways.

Boondoggles galore

Even when we make efforts to modernize our infrastructure, they have proven almost comically incompetent. Boston’s Big Dig (Central Artery/Tunnel Project) highway project rewrote the book on great planning disasters for its cost overruns and delays.

A Transportation Research Board report found in 2003 that the project had more than tripled in cost, adjusted for inflation, and was to be delivered six years late. In 2012 a state official told a state legislative committee that the final cost was nearly $25 billion, $10 billion more than previously reported. The federal government was not obligated to pay much of the cost escalation, leaving the state with a $7 billion deficit, which was financed with bonds.

Similar folly can be seen on the West Coast, in the case of the replacement of the eastern section of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (Yerba Buena Island to Oakland). University of California Berkeley scholar Karen Trapenberg Frick outlined how the cost rose from an estimated price of $250 million in 1995 to $6.5 billion by 2013. Much of this was due to political pressures from elected officials and other local interests, according to a report prepared for a state senate committee.

A similar picture emerges in the transit sector (which has the worst ASCE grade with a “D-”). The Marron Institute at New York University blamed intense lobbying, regulatory delays, and inflated labor costs for saddling the U.S. with “among the highest transit-infrastructure costs in the world,” far higher not only than China, which one can ascribe to less cumbersome processes, but than countries like Sweden, Italy, and Turkey.

Marron notes that costs for New York’s Second Avenue subway clocked in at 8-to-12 times more expensive than what international analysis suggested as the baseline cost. The transit authority used little standardization of station and tunnel elements, in contrast with European and Japanese systems.

Strict overtime rules, local union agreements that limited the available labor pools geographically, and an unwillingness to address staffing and labor agreements made the American project more costly. Labor costs consumed a greater percentage of construction than in countries like Britain and the Netherlands.

But perhaps the award for the most egregious failure belongs to the proposed California high-speed rail line from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Its costs escalated from $33 billion in 2008 to as much as $128 billion today.

Given that less than one half of the proposed system is under construction at this point, and not a single shovel has yet been turned on the most challenging sections (which will require extensive tunneling), considerable additional cost escalation would not be surprising.

Mandated by state law to provide non-stop San Francisco to Los Angeles service in 2 hours and 40 minutes, the project will now work in a “blended” fashion, mixing with conventional speed trains in parts of the San Francisco and L.A. metropolitan areas.

Despite these out-of-control costs, the Biden Administration keeps sending funds to the high-speed train, which does not even have an estimated completion date. Perplexingly, the Biden Administration is sending funds to a Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) subway project in the San Jose area that has escalated from an original cost projection of $4.4 billion to $12.8 billion, with a completion date now extended from 2026 to 2037.

In an action with “keystone cops” overtones, the local transit board (Valley Transit), responsible for providing the subway cars, has decided to buy them now rather than coordinating with the anticipated opening date now pushed back more than a decade. The cars will be used on the rest of the BART system, which having lost nearly 60 percent of its pre-pandemic ridership, hardly needs them.

Love in the wrong places

The massive transit expenditures also demonstrate the bizarre priorities that further hamper the creation of usable infrastructure. In California and many other areas, transit investments are made even though the vast majority of commuters are forced to travel on the worst maintained roads in the country. This is happening despite the fact that 93 percent of San Jose metro commuters either travel to work by car or work at home.

As in transportation, energy policy seems to be built more around the preferences of political forces—the wind and solar industries, for example—than meeting the needs of the vast majority. The move to “net zero” reveals a penchant for fantasy over reality. The move to electrical vehicles is part of a messianic plan to change what Americans drive—even though it requires massive investment in charging stations; the $7.5 billion allocated for this purpose has built only seven such stations, according to the Washington Post.

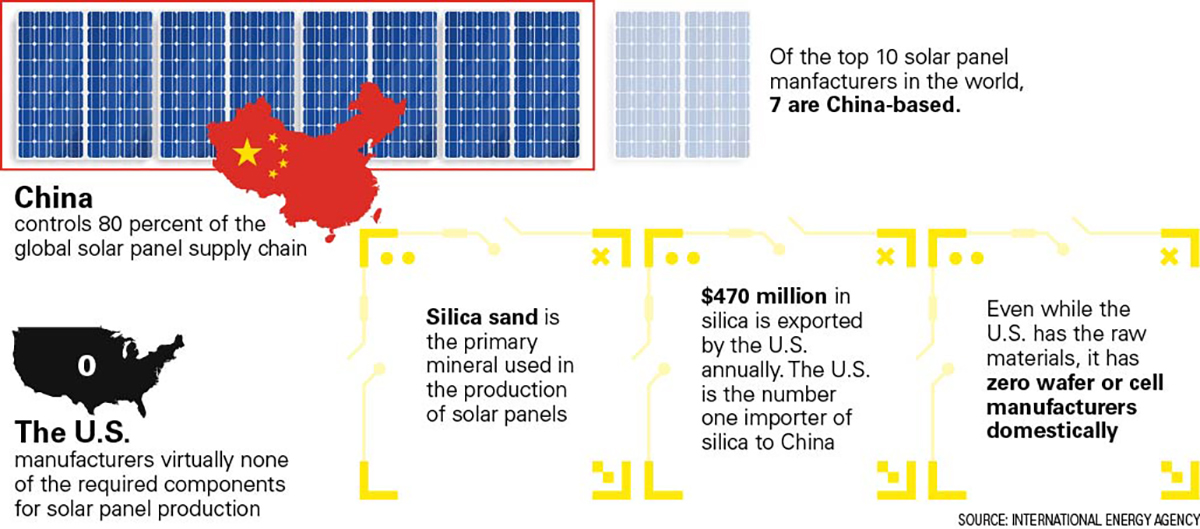

EV mandates also have the potential of shifting the core automobile industry to China, which dominates the solar panel industry’s requisite rare earth minerals and the technology for their processing. Continuing on a coal plant building spree, China emits more GHG even as it dominates the EV industry both in North America and Europe; today China now produces twice as many EVs as the U.S. and the E.U.

The new gridlock

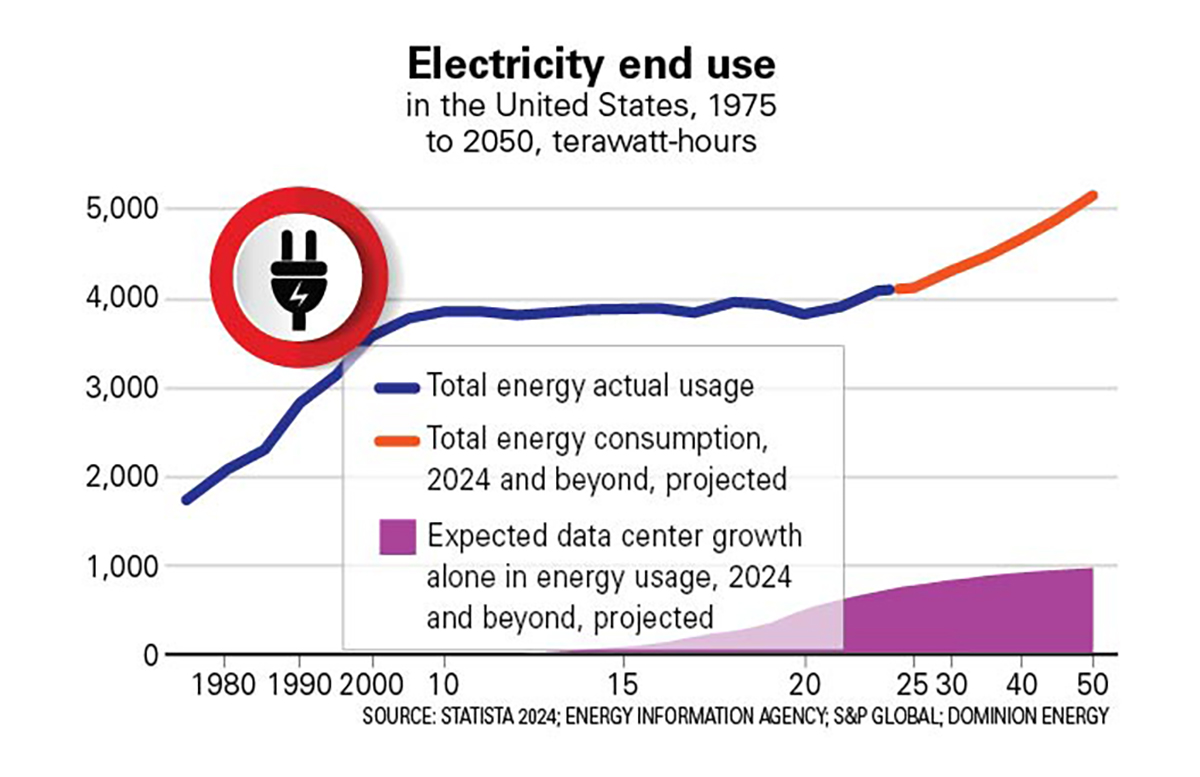

Even Elon Musk predicts that current policies will leave us with severe shortages to power EVs, not to mention the huge demands to power artificial intelligence data centers. Microsoft alone is opening a new data center globally every three days. These power-hungry operations are expected to grow from 4.5 percent of energy demand to 10 percent by 2035.

Artificial intelligence and data center demand are leading to massive expansions in projected energy needs amidst current limited supply. Last year, space for data centers in the U.S. grew 26 percent, with Microsoft and Google investing heavily in new facilities. These centers are unlikely to be built in areas that rely on renewables; Georgia, in a bid to win over new data centers, has just opened a large nuclear plant to meet this need while not boosting greenhouse gases.

Unlike China, which continues to build ever more coal and fossil fuel plants, and plans to expand nuclear power, the Biden Administration is placing its energy hopes on wind and solar energy, widely associated with high costs and low performance.

The juxtaposition of waning energy capacity and soaring demand will not end well. Just a few months ago, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s chairman admitted that “we face unprecedented challenges to the reliability of our nation’s electric system.”

The impracticality of the focus on solar and wind can be seen in repeated government funded failures such as Solyndra, a manufacturer of solar panels and recipient in March 2009 of a $535 million federal loan guarantee, sweetened with a California tax break of $35 million. The company filed for bankruptcy two and a half years later. The ranks of defaulting debtors include Abound Solar, Calisolar, Fisker Automotive, and A123 Systems, together squandering hundreds of millions in taxpayer dollars.

A substantial body of literature has developed over the past half century documenting the failures of large infrastructure projects, echoing the phrase of British economist Richard Tol on the economics of climate change: “The uncertainty about the benefits is larger than the uncertainty about the costs.”

Can we turn this around?

As long as megaprojects are driven by narrow politics and “process” as opposed to efficiency, the country will continue to lag in improving its infrastructure despite massive subsidies from government. Professor Bent Flyvbjerg at Oxford University has identified a strong tendency of “optimism bias” in which project officials unconsciously underestimate costs and overestimate benefits (such as use). Even worse is “strategic misrepresentation” which intentionally misleads on such issues as costs, scheduled, risks, customer usage, and other benefits.

Flyvbjerg et al also suggest the adoption of “reference class” forecasting the planning for major projects. The use of reference class forecasting by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky contributed to their receipt of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Economics. The basic principle is to identify a class of projects similar to the project being evaluated and examine the results based on actual outcomes toward the end of eliminating any optimism bias.

A starting point should be to empower megaproject builders to realign practices with the best practices found in the international market, as Marron recommends. There also needs to be a realistic assessment of how to meet our energy needs with a focus on the most practical ways to create a better system.

Reviving the workforce

Such reforms in procurement and monitoring are part of the solution, but we cannot afford to ignore human factors critical to the future of the industrial base. Non-Western competitors, notably China, are building a skilled workforce that can operate sophisticated, automated facilities.

In contrast, only five percent of American college students major in engineering, compared with 33 percent in China; as of 2016, China graduated 4.7 million STEM students versus 568,000 in the United States, as well as six times as many students with engineering and computer science bachelor’s degrees. “In the U.S., you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I’m not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields,” Apple CEO Tim Cook has observed.

American firms, in both high tech and low, unsurprisingly look abroad for labor, even at home. Foreign workers now account for almost 75 percent of Silicon Valley’s tech employment. In terms of our domestic workforce, we continue to misallocate resources, placing far too much emphasis on four-year college degrees and not enough on the cultivation of necessary skills.

Even among those who manage to finish, more than 40 percent of recent graduates aged 22 to 27 are underemployed, meaning that they’re working in jobs that don’t require their degree, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York reports. No surprise that more young people are choosing to eschew college and look for more practical, skills-based employment.

Ned Hill, who is affiliated with the Ohio Manufacturing Institute at The Ohio State University’s College of Engineering, sees a great opportunity for the new generation, as 50 percent of active industrial workers are above the age of 45. Shortages extend from the factory floor to car mechanics to riggers.

The good news is that states such as Ohio, North Carolina, Nebraska, and Tennessee have developed flexible training programs following the successful approach employed in European countries like Germany, Sweden, and Denmark.

Much more is needed on the national level. As President Biden looks to eliminate college debt, manufacturers complain they can’t find skilled workers. Certainly subsidies are not solving the problem; U.S. manufacturing remains stagnant despite reshoring oriented measures from the Biden Administration. But money is not everything; the conditions imposed by the administration have also saddled companies with requirements on child care and gender issues, among others, helping make it 40 percent more expensive to produce chips here than overseas.

Political problem, political solution

Restoring our infrastructure requires a political solution. Even in the recent past, public officials have cut through red tape to get projects done on time, and even under budget.

Further rapid repairs to freeways in Los Angeles (the I-10 earthquake in 1994 and fire in 2023) and Philadelphia (the I-95 truck collision in 2023) are an indication that public agencies can be particularly efficient in emergency situations. The private sector has built a new near-high speed rail line in Florida that is already carrying riders between Miami and Orlando.

Federal, state, and local officials should examine success stories such as these and incorporate appropriate strategies to improve more routine projects, to both speed up project delivery and control costs.

When federal funding is involved, the president has considerable latitude to expedite regulatory processes to speed project delivery. The national administration, as well as state and local governments overseeing infrastructure projects, should use all their authority to minimize project delays and cost increases. This includes both administrative and legislative remedies.

Ultimately there needs to be a political consensus of what constitutes the national interest. As long as infrastructure projects are viewed as manna for the political class and its allies rather than a way to address serious issues, we will continue to repeat the cost overruns and misdirection that has characterized the past few decades. Rebuilding America does not require adherence to either a libertarian or statist model; it needs a focus on common sense ways to address common needs.

As analyst Aaron Renn has suggested, we need “a populism that builds,” a policy agenda that both demands efficiency but also seeks results—the very things that won both World War II and the Cold War.

Authors Joel Kotkin and Wendell Cox are, respectively, the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute; and the principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.