The White House and the Republican National Committee agree on one thing at least: The sale of surplus federal land could help alleviate a crushing shortage of affordable housing.

Proposals to sell federal land to builders for the construction of homes remarkably made their way into both the RNC’s 2024 platform and President Joe Biden’s latest housing plan, as both parties struggle to reckon with voter dissatisfaction over the soaring cost of the nation’s limited supply.

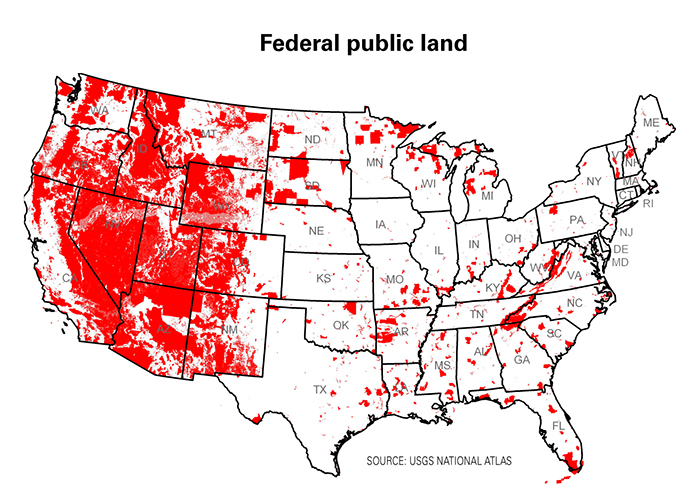

It’s simple in theory: The federal government—which owns roughly 28 percent of the land in the U.S.—would open up bidding for parcels to developers who commit to keeping a certain percentage of the units at an affordable level for the local population.

The emergence of bipartisan support for the idea is evidence that policymakers are getting increasingly desperate to resolve a housing affordability crisis that is largely the result of restrictive local zoning laws over which Washington has little control. But there are numerous hurdles to developing housing on federal land, including clashing visions between the two parties over how the program would work and concern among environmentalists about a potential giveaway to developers.

“Imagine having a county where over 90 percent of the land can’t have housing despite many acres being appropriate for development, all because it’s federally managed,” Rep. John Curtis (R-Utah) said. “The idea is a practical solution and including it in the Republican platform is welcome news for Utahns struggling with housing affordability.”

Curtis, who is running for the Senate this year, has introduced a bill to enable the sale of federal lands to states and local governments to address housing shortages. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) has introduced a companion bill in the Senate.

Some 63 percent of Utah’s land is federally owned, as are vast tracts of California (45 percent) and Nevada (80 percent), among other states.

“Senator Lee has invited his Democrat colleagues to join in support of his HOUSES Act,” said Billy Gribbin, communications director for Lee, whose co-sponsors are all Republican.

The White House is taking a different—and more circumscribed—approach than the one outlined in Lee’s proposal.

The administration effort is focused on “vacant and surplus federal lands that are within existing development zones and in metros that face shortages of affordable housing,” said a White House aide who was granted anonymity to discuss differences with the Lee bill.

Given those careful considerations, the overwhelming majority of federal lands are unsuitable for housing development and not part of our focus,” the aide said.

Administration officials have also warned that the bill provides no guarantee that the sold land would go toward affordable housing and has no way to ensure compliance with the promise that it would.

The affordability problem is acute. Home prices reached a record high in May. The U.S. is short nearly 4 million units to meet demand, according to Freddie Mac, with construction rates falling in the years since the 2008 financial crisis. About 9 in 10 Gen Z and millennial respondents to a Redfin poll said housing affordability is a key motivation in how they will vote. And some 64 percent of homeowners and renters say the affordability crunch makes them feel negatively about the economy.

The idea itself “makes a lot of sense—there is an enormous amount of federal land out there that is sitting empty or completely unutilized, and you could build a lot of affordable housing there if you’re smart about it,” said David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference, a coalition of housing groups.

But “you need to actually understand how markets work and work with for-profit developers and recognize that you’re competing against all the other land and opportunity out there,” he cautioned. “You have to make it worth it to housing developers who are making decisions based on data.”

Lots of federal land is unsuitable for residential construction. And the places where the government owns the most land, particularly in the West, are not always near areas with the biggest housing needs, or often lack even basic infrastructure like roads or sewers.

“The U.S. owns a lot of Nevada and Wyoming, but apart from Las Vegas those are really not high-cost markets,” said Brett Theodos, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. “To make a difference, it’s going to really have to be in places that are having a supply crunch.”

The “topography of the land” is also important, according to Jim Tobin, president and CEO of the National Association of Home Builders: “How much earth-moving is it going to take?”

“On its face, it’s a good idea,” he said, but the housing shortage is too broad and deep an issue for it to be a panacea. “The supply crisis is not confined to cities with older commercial buildings or a few hundred acres in the desert of southern California,” Tobin said.

“Home production is community by community—it’s as inherently a local issue as anything, and the federal government has very few arrows in its quiver,” he added.

Even after parcels are selected for bidding, there’s no guarantee developers won’t face the same local NIMBY pressures that have stalled other projects to build more affordable housing.

A plan to build 1,200 affordable units on a West Los Angeles campus owned by the Department of Veterans Affairs has been mired in protracted litigation amid resistance from the wealthy Brentwood area surrounding it.

Veterans have sued the government, arguing that campus land the VA leases to a private school, a baseball field for UCLA and an oil drilling operation does not help veterans. A judge in December ruled that the suit could go forward.

There’s no shortage of obstacles, but it’s worth a shot, according to Sunia Zaterman, executive director of the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities.

The council “strongly supports” the use of federal land for housing, she said, adding, “We want to make sure that public housing authorities are designated as eligible partners or eligible recipients of grant money.”

The bipartisan interest is encouraging, she said.

“The federal government really does not control the housing market in the way that people think,” Zaterman said. “But I do think people are understanding that we’ve got to push that housing development and supply issue to the top of the agenda.”

Housing “is an area where we have seen growing bipartisan musings and talking points, but the parties are still not fully agreed on the details,” Theodos said.

Indeed, environmentalists are skeptical about Lee’s legislation.

“What we’re seeing from Republicans is ideological—any excuse is a good excuse to get rid of public lands,” said Brett Hartl, chief political strategist for the Center for Biological Diversity Action Fund. “This is part of a decades-long effort by a subset of Republicans that have a deep, deep antipathy to public lands.”

Hartl said he supported the White House’s recently announced plans to sell off 20 acres of Bureau of Land Management land to Clark County, Nevada.

“If it’s a particular situation in solving one particular city’s needs, that’s fine,” he said. “But as a top-down directive to solve the housing crisis by getting rid of public lands, that’s really just about getting rid of public lands.”

The Center for Western Priorities, a conservation group, also commended the White House plan while slamming Lee’s proposal in a statement.

“The Interior Department is showing how public lands that are already well-suited to development can be part of the housing solution, with appropriate safeguards to make sure the housing is affordable and doesn’t end up as trophy homes for billionaires,” said Aaron Weiss, the group’s deputy director.

“That’s going to happen 20 or 30 acres at a time, not by handing thousands of acres of public land to private developers for sprawling suburbs and McMansions across pristine lands like Senator Lee dreams of,” he added.