Would a YIMBY building boom rejuvenate urban family life or produce sterile, megacity hellscapes?

Housing Boom = Baby Bust?

America’s low birth rate is in the news again, thanks largely to Vice Presidential candidate Sen. J.D. Vance’s (R–Ohio) resurfaced comments criticizing America’s anti-family “childless cat lady” ruling class, as well as his various policy proposals—from higher taxes on the childless to more votes for parents—to get Americans breeding again.

Vance’s comments have prompted a flurry of think pieces that dispute his specific points while accepting his basic argument that various, liberal-coded public policies are contributing to America’s declining birth rate—particularly in large, high-cost cities.

Derek Thompson in The Atlantic argues that “the steady march of the childless city is not merely the inevitable result of declining birth rates. It’s the result of urban policy, conceived by, written by, and enacted by liberals.”

Thompson singles out excessive land use regulations for making life difficult for urban families. More regulation means higher housing costs and higher childcare costs (by limiting the number of lower-wage childcare workers who can live in the city). Neither is good for keeping families in town.

Writing at Discourse, Addison Del Mastro is even more direct, saying that the most “pro-natalist” policy the government could adopt “would be to force down the cost of housing through supply—getting out of the way of the normal process of building, i.e., slashing the red tape of zoning and related elements of the land use regime.”

This is a common, plausible YIMBY refrain—lowering the cost of housing through deregulation will enable more people to go forth and multiply.

The idea is not without its critics.

At a recent campaign rally, former President Donald Trump dusted off his argument from his 2020 campaign trail that “forcing” more low-income apartments into the suburbs will ruin family-friendly neighborhoods.

Other pro-natalists have argued that because high-rise apartment developments are associated with lower fertility rates, allowing more of them could reduce the number of births.

So, will a YIMBY building boom produce a baby boom or bust?

Housing cost

As mentioned, the basic assumption of the YIMBY natalist case is that there’s a pretty tight link between housing costs and people’s willingness to start families. It’s an assumption that appears to be correct, says demographer Lyman Stone.

“Housing costs are one of the biggest line items in raising a child because kids tend to take space and we know when there are plausibly exogenous shocks to housing costs, that fertility responds,” Stone said.

As evidence, he cites a study of changes in fertility rates in the United Kingdom during the Great Recession, where government policy interventions dramatically lowered the costs of mortgages for some, but not all, homeowners.

Households that were eligible for lower mortgage rates saw increased birth rates. The literature shows a similar dynamic for renters too, said Stone. When rents drop, births go up.

In his Atlantic article, Thompson cites a recent research brief from the Economic Innovation Group showing that while high-cost, high-regulation urban areas have seen a huge drop in their young child population, quickly growing exurban counties in the Sun Belt (where housing supply is more elastic) are adding lots of toddlers.

The relationship between housing regulation and housing supply is also pretty robust and straightforward: more regulation leads to less supply, which in turn drives up home prices and rents.

Reducing regulation would increase supply and lower home prices and rents. The most straightforward assumption would be that this would lead to an increase in the number of children people have.

So case closed?

Housing density

Not necessarily.

In a recent post, the popular pro-natalist X account More Births pulls together a lot of international data on density and fertility to argue that “apartments in high-rises are inherently anti-family. The more of them you build, the lower fertility will be.”

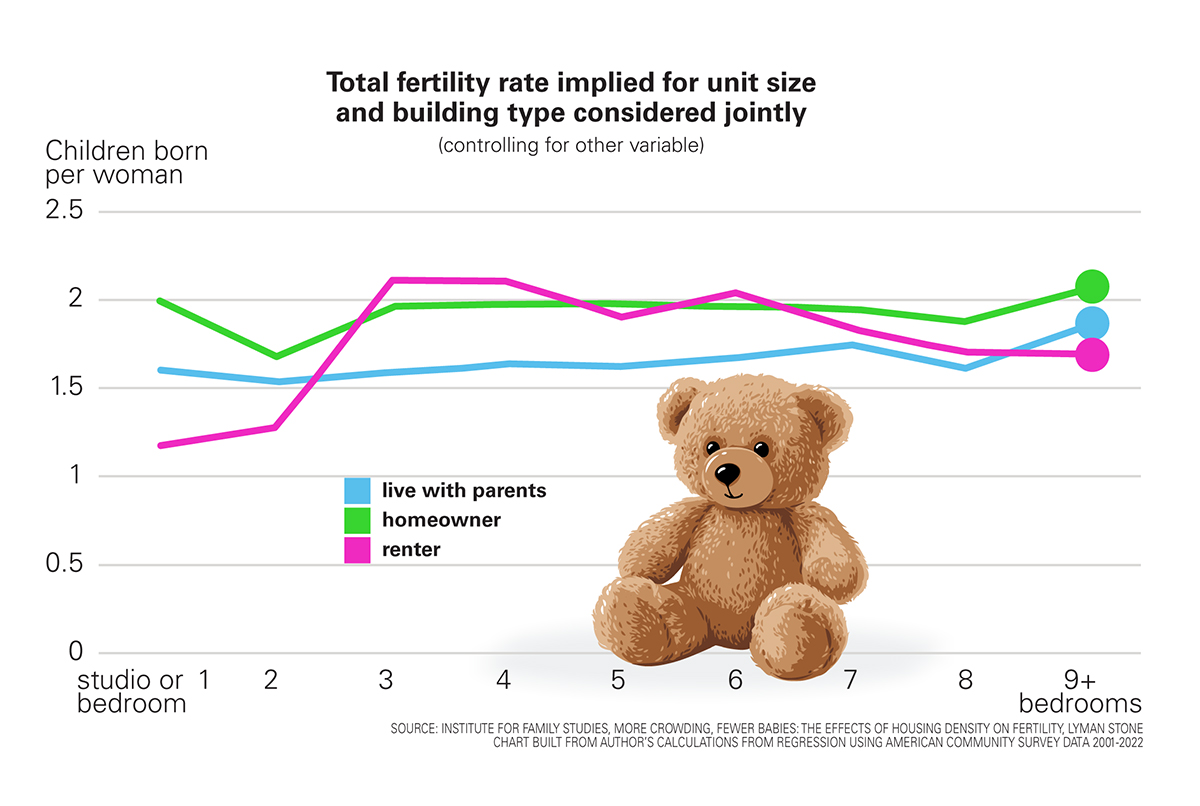

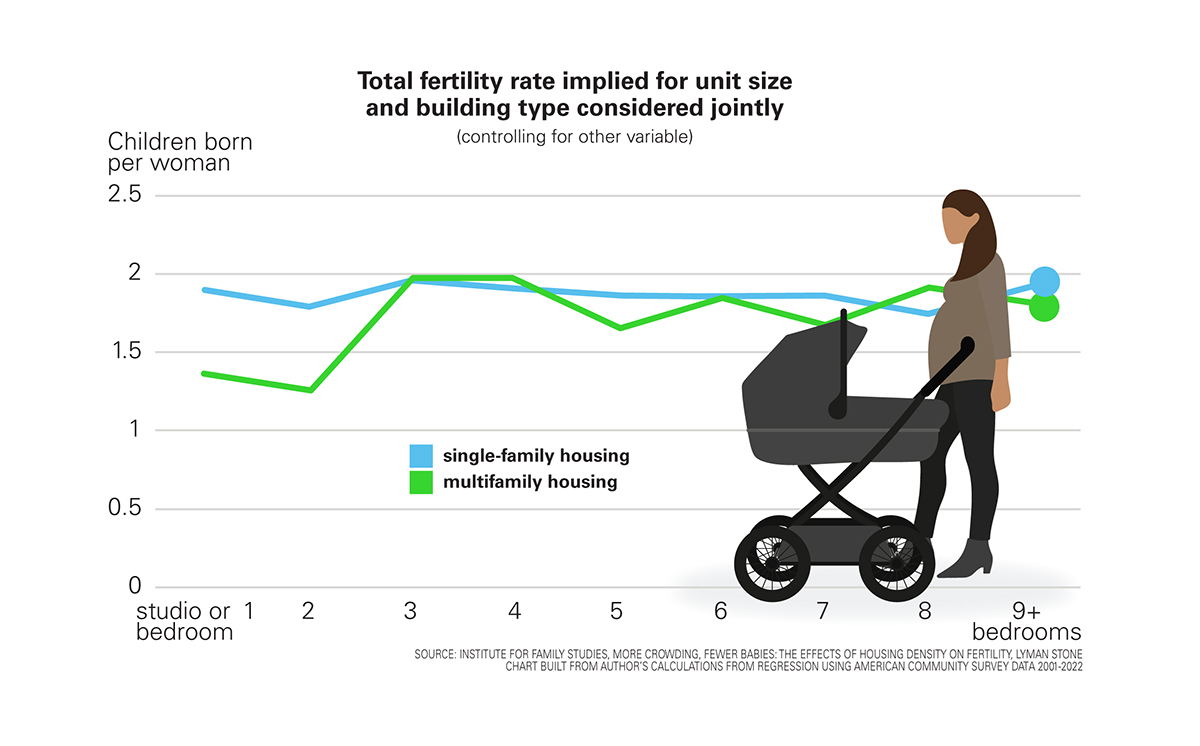

In an article for the Institute for Family Studies (IFS), Stone conducts a more thorough parsing of the data and comes to a similar conclusion.

He finds that while many measures of density don’t have much of an impact on the number of children women have, others do.

The number of people per square mile doesn’t seem to affect fertility rates much, except for a slight negative effect in the densest areas. Likewise, whether a woman lives in single-family or multifamily housing doesn’t make much of a difference either.

But other measures of density—like the number of people per bedroom and unit size—do matter a lot, argues Stone.

Women who live in smaller one- and two-bedroom apartments have fewer children than women who live in larger apartments. Likewise, women who live with their parents and those in households with more people per bedroom have lower fertility rates.

There’s also a significant interactive effect between various measures of density.

“When women live in smaller, more crowded houses, they have fewer children. This is especially true if those small, crowded houses happen to be in areas of high population density,” writes Stone. In Asian megacities where basically all the housing is small, overcrowded housing units, fertility rates are at rock bottom.

Looking ahead

When talking about affordability, YIMBYs like to invoke the concept of filtering. This is the idea that building new, expensive housing that only some people can afford still improves affordability for everyone.

High-income people move into the new units, lowering demand (and therefore prices) for older, existing units.

One could similarly argue that building lots of small units associated with lower fertility rates would still improve overall fertility. Existing groups of single roommates occupying family-friendly multi-bedroom apartments could move into studios of their own, opening up their former homes to families with children.

Stone is critical of this “filtering for families” idea in the long run.

“It’s one thing to say we should build small apartments to get young people out of roommate situations that we’d like to go to families,” he says. “In the future, you’re just adding more and family-unfriendly housing that the next generation has to deal with.”

Stone argues that if YIMBY-style zoning reform focuses only on adding denser housing in already dense urban areas, cities will eventually become dominated by housing types that are bad for family formation. People’s willingness to have children will fall as a result.

Salim Furth, a housing economist at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, is more copacetic.

While there’s some truth to the idea that ultra-dense megacities would lower fertility rates, it would take a truly eye-popping, improbable level of high-density redevelopment to turn Boston or New York City into low-fertility Hong Kong or Seoul, he says.

And that’s not the result we should expect from free market housing reforms.

“In a market economy, people build housing of lots of different types,” says Furth.

He notes that huge swaths of the YIMBY-style policy platform would produce the kinds of housing that appear to be good for family formation. Minimum lot size reform would enable the construction of more affordable starter homes. Eliminating requirements that apartments have two staircases would make family-sized apartment floor plans easier to build.

In his IFS article, Stone mentions common YIMBY policies like allowing more accessory dwelling units and eliminating minimum parking requirements as reforms that would reduce overcrowding and produce more family-friendly units.

Furth also cautions that housing cost and availability are only part of the puzzle. The wealthiest Americans, who can afford as much floor space as they want, are not necessarily the ones having the most children.

Thompson’s Atlantic article spends a lot of time describing the cratering of the toddler populations in large cities during the first year of the pandemic. That was also a time when rents and home prices in the urban cores of large cities were falling fast.

That short-term decline in prices didn’t act as a magnet for families flooding into the city. Other factors, like prolonged school closures and rising crime, plausibly played a bigger role in families deciding to get out of the city.

The “housing theory of everything”—the idea that housing regulation impacts almost every social and economic issue—is an increasingly popular idea. I’ve made a version of it myself. But one shouldn’t overstate the case that housing is the only thing that matters.

Still, economists are trained to think on the margins. The marginal impact of reducing regulations on building new homes will reduce housing costs and increase the availability of all different types of housing. We should expect that to make it easier for people who want families to have them.