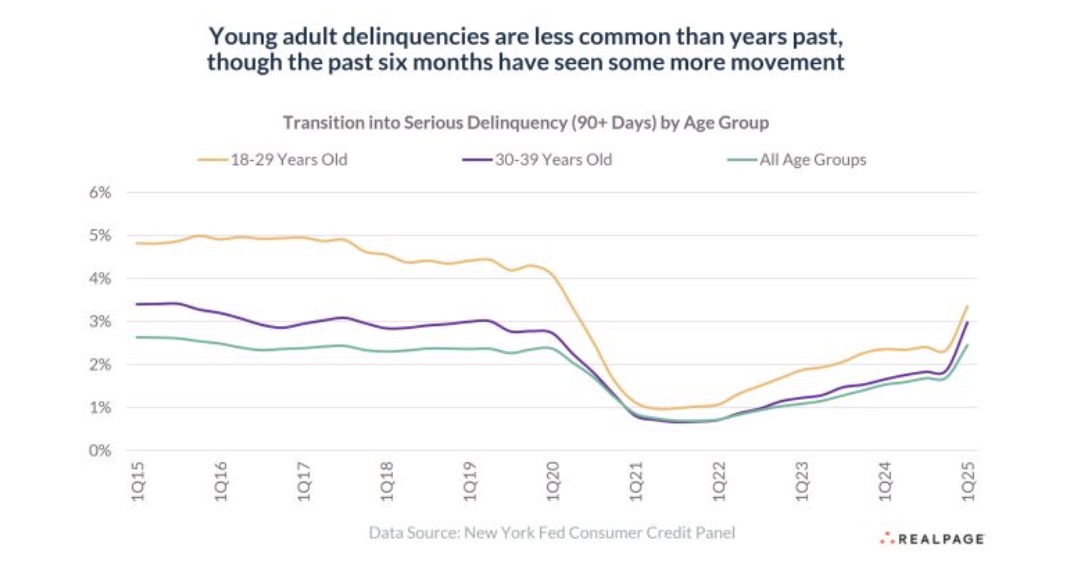

Consumer delinquencies are rising, but context matters, especially in a market still normalizing after pandemic-era disruptions. As the multifamily sector seeks clarity amid macroeconomic crosscurrents, one trend is beginning to raise flags: a sharp uptick in consumer debt delinquencies. While much of the media has seized on this data to sound the alarm, industry experts suggest a more nuanced view, especially when applied to the rental housing market.

RealPage Chief Economist Carl Whitaker recently shared updated data on serious delinquencies (defined as 90+ days past due), highlighting that while delinquencies are rising, they’re mostly reverting to pre-pandemic norms. “The past four years were abnormally low,” Whitaker wrote, noting that what looks like a spike may actually be a reset after COVID-era protections and payment holidays kept delinquencies artificially suppressed.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s latest Consumer Credit Panel data confirms this trend. Delinquencies in auto loans, credit cards, and personal loans are climbing—but not yet at crisis levels. Still, as Whitaker pointed out, “the pace of the recent uptick is more of a fair concern.”

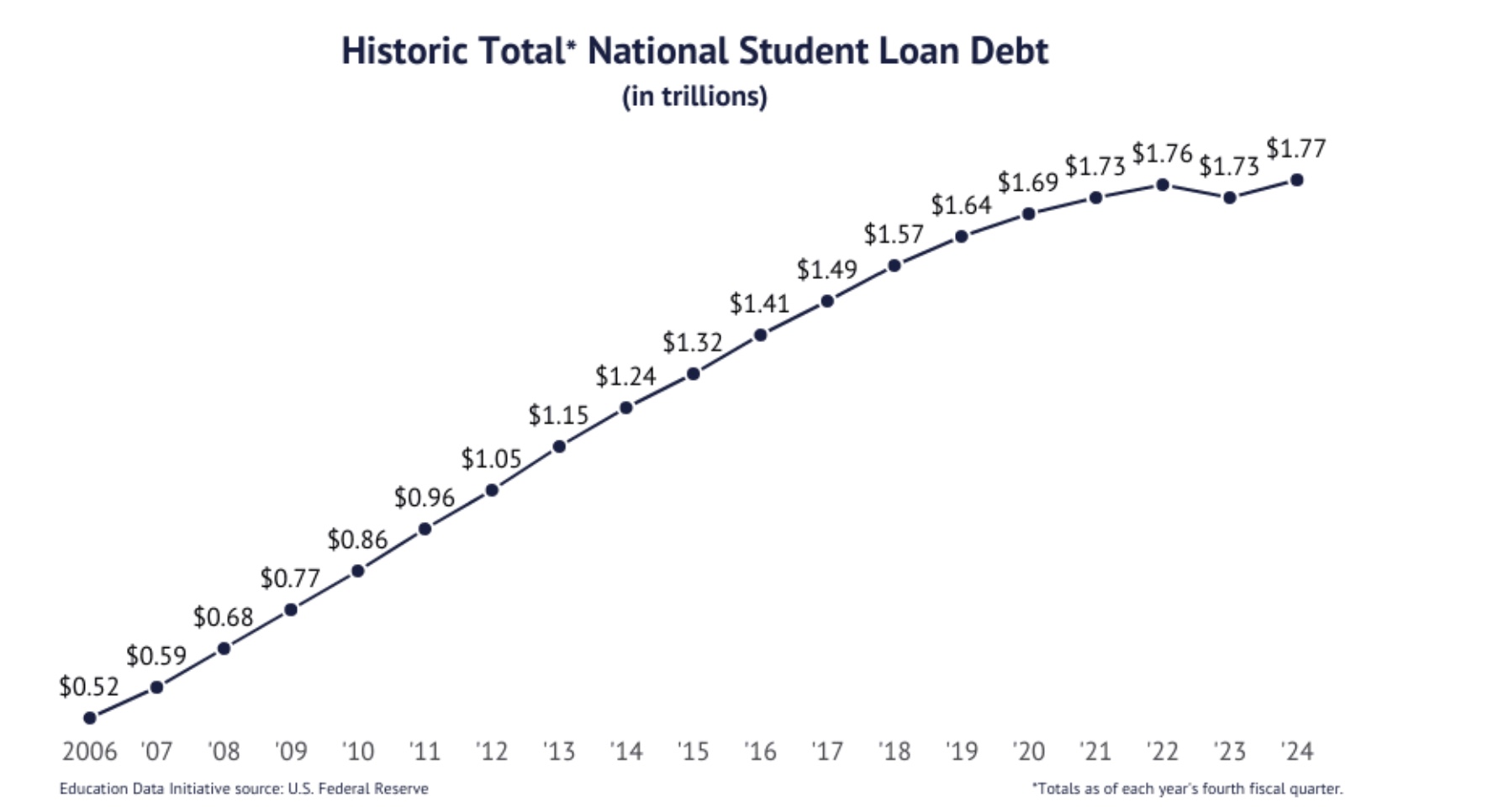

One of the less discussed but increasingly visible stressors is student loans. As of Q4, 2024, national student loan debt in the United States totaled $1.777 trillion.

As Leland Spelman, a commenter on Whitaker’s LinkedIn thread, noted: “The hidden wave of delinquencies may come from the student debt crisis, with nearly 27 million borrowers not paying and most in some form of deferral or modification.”

With the Department of Education now directing wage garnishments of up to 15 percent for non-payers, the financial pressure could mount fast.

Whitaker responded that “garnished wages may sting some households,” but also pointed to a silver lining: rent-to-income ratios, particularly in Class A and B properties, have declined over the past 12 to 24 months. This, he suggests, may offer a buffer against systemic strain in the institutional rental market.

Still, the broader context matters. During COVID, millions of Americans paused not just rent but student loans, credit card payments, and even mortgage obligations. That temporary freeze now appears in the data as a jagged dislocation—a sharp drop during the pandemic followed by a fast climb as support programs sunset.

But Whitaker and others argue that normalizing doesn’t necessarily mean crisis. In fact, the key renter demographic—ages 18 to 29—is showing stronger credit performance than in the last cycle. Serious delinquency gaps between this cohort and older renters have narrowed significantly, suggesting today’s young adults are weathering economic shifts with more financial literacy—or at least, more caution.

Still, that student debt overhang remains the elephant in the room, notes Whitaker. If millions of households begin facing garnishments, their ability to meet rent obligations could erode, particularly in markets with already-tight affordability.

Bottom line? While rising delinquencies are worth watching, context is everything. The COVID anomaly distorted the credit landscape, and we’re only now beginning to see the aftershocks. Whether those aftershocks remain ripples, or become waves, may depend on how well renters can absorb the impact of resumed loan payments and how operators respond to early signs of stress.