New research suggests that unintended consequences of tenant protection laws may be hurting the very population they are meant to protect.

These laws are designed to shield renters from discrimination, eviction and screening practices that may unfairly keep them out of housing. Yet a new study finds these well-intentioned regulations drive rents higher, particularly for the lowest-income renters who can least afford it.

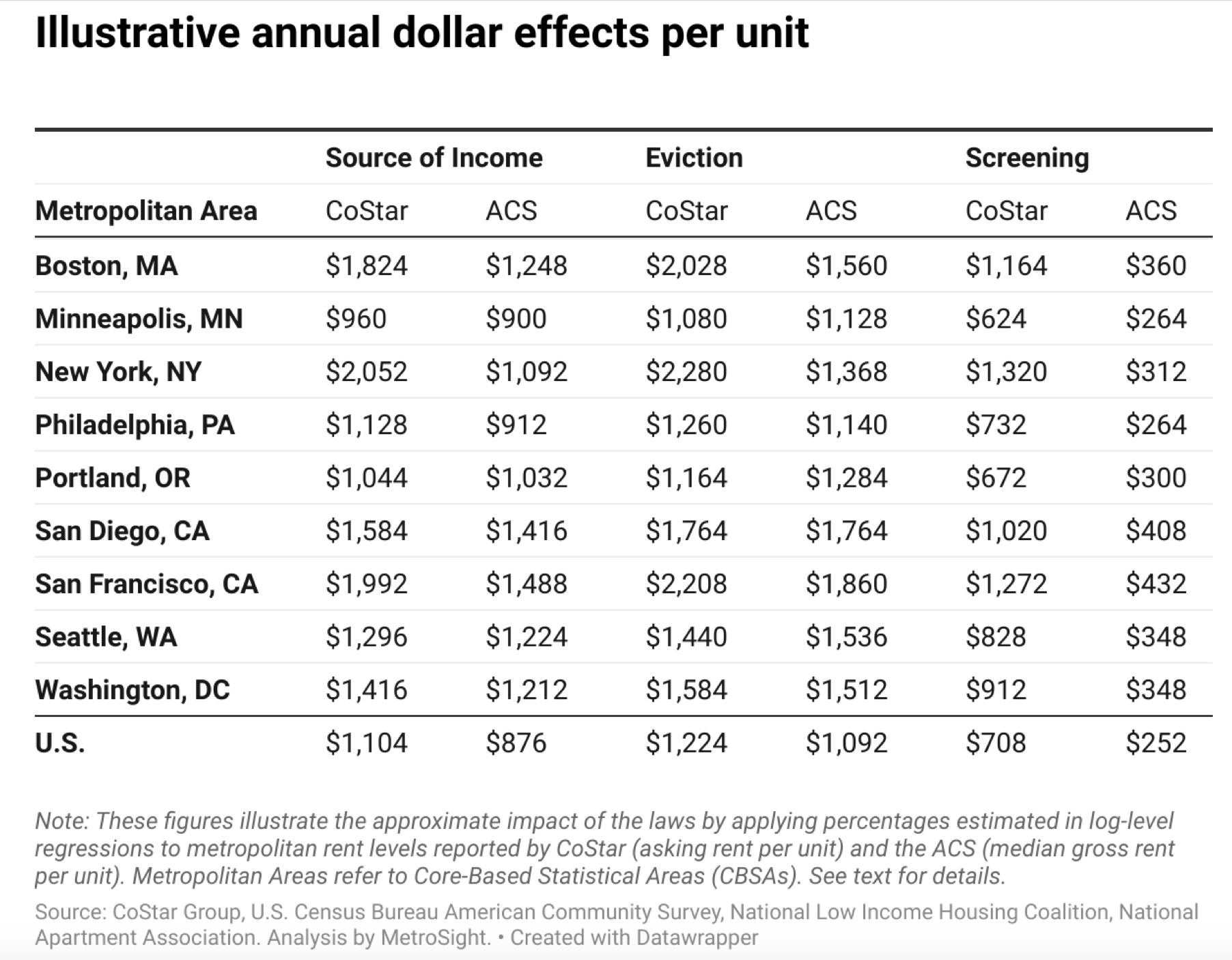

That’s the conclusion of a study by MetroSight, funded by the National Multifamily Housing Council and the National Apartment Association. Using data from CoStar and the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS), researchers analyzed four categories of laws—source-of-income protections, eviction restrictions, screening limits, and state-level preemption statutes—and their impact on rental markets across U.S. metros.

The analysis builds on a February 2025 report showing how regulations raise development costs for multifamily housing. This time, the focus turned to whether those same rules lead to higher rents. The findings are striking.

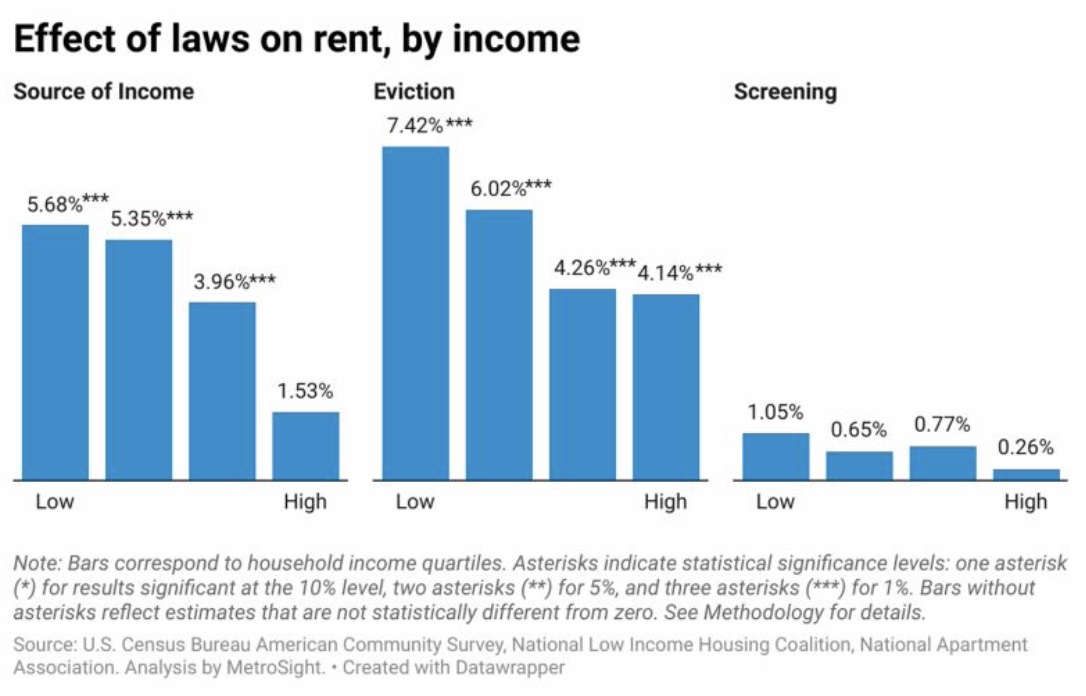

Eviction mitigation laws, such as “just cause eviction” and “right-to-counsel,” are linked to average rent increases of 6.5 percent, according to ACS data. By extending eviction timelines, adding legal costs, and increasing the risk of unpaid rent, these rules raise owner risk exposure. The burden falls most heavily on those with the least means: rents increased 7.4 percent for the lowest-income renters, compared with 4.1 percent for the highest-income households.

Source-of-income laws, which require property managers to treat government vouchers as income in the application process, led to rent increases of 5.2 percent overall, and 5.7 percent for the lowest-income renters.

Applicant screening restrictions, which limit the use of credit and criminal histories, including past evictions, increased rents by 1.4 percent based on ACS data—or by as much as 3.4 percent using CoStar’s market data.

By contrast, preemption laws that prevent cities from enacting rent control or eviction restrictions had no statistically significant effect on rents.

These results reinforce what property owners and managers observe, that when landlords cannot fully evaluate applicants, especially in an era of rising fraud, the risk is real, not merely perceived.

As rental housing economist Jay Parsons explained on his Rent Roll podcast: “When you can’t properly measure risk, you take on more risk and that results in higher rents.”

This is why tenant protection laws often backfire. They don’t eliminate risk, they redistribute it. And in a market where housing is treated as a capital investment, the cost of risk is almost always passed down to renters.

The findings also sparked debate about how to interpret these impacts. Paul Fiorilla, Director of U.S. Research at Yardi Matrix, noted on Parson’s LinkedIn page that the report’s use of “annually” could be read as implying recurring increases of 13 percent or more.

Parsons clarified, writing, “I read it as a structural lift to the rent floor, not a recurring 13 percent additional per year.” That distinction is critical. The study’s log-linear model measures how rents reset when a law takes effect, not compounding annual growth.

Even so, these one-time adjustments are significant for renters already stretched thin.

The findings echo a broader body of research on rent control. Markets with strict rent caps often see constrained new development, diminished property reinvestment, and ultimately, higher average rents across the board.

The takeaway is that tenant protection laws, however well-intended, often trigger costs that landlords cannot absorb and therefore shift to renters. For policymakers, the challenge is finding solutions that protect renters without narrowing affordability.

The Metrosight study is available here.