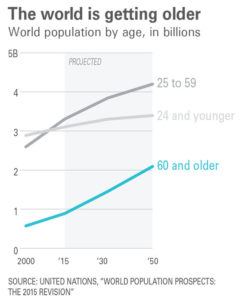

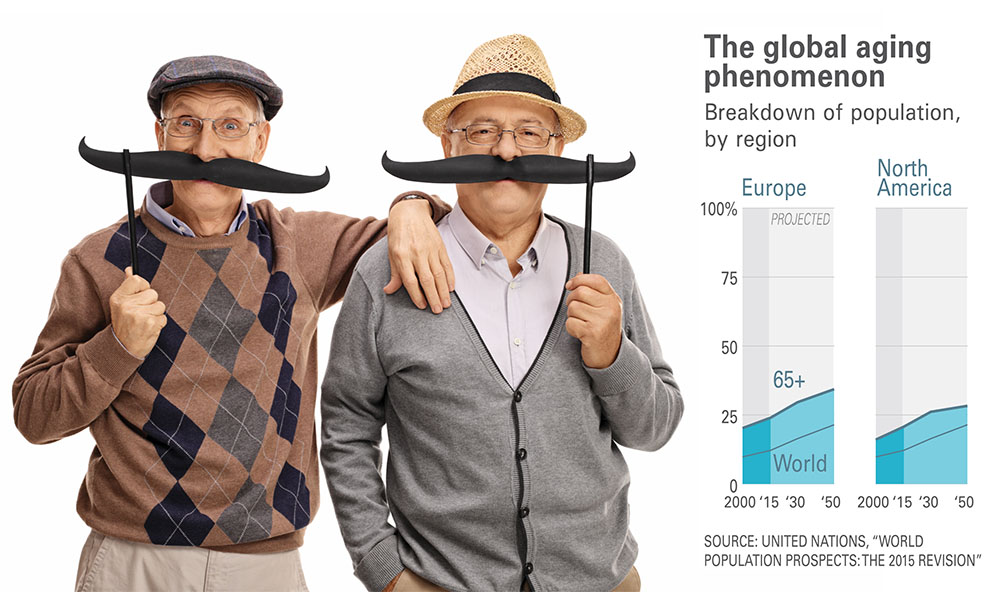

Before our eyes, the world is undergoing a massive demographic transformation. In many countries, the population is getting old. Very old. Globally, the number of people age 60 and over is projected to double to more than 2 billion by 2050 and those 60 and over will outnumber children under the age of 5. In the United States, about 10,000 people turn 65 each day, and one in five Americans will be 65 or older by 2030. By 2035, Americans of retirement age will eclipse the number of people aged 18 and under for the first time in U.S. history.

The reasons for this age shift are many—medical advances that keep people healthier longer, dropping fertility rates, and so on—but the net result is the same: Populations around the world will look very different in the decades ahead.

Some in the public and private sector are already taking note—and sounding the alarm. In his first term as chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, with the Great Recession looming, Ben Bernanke remarked, “in the coming decades, many forces will shape our economy and our society, but in all likelihood no single factor will have as pervasive an effect as the aging of our population.” Back in 2010, Standard & Poor’s predicted that the biggest influence on “the future of national economic health, public finances, and policymaking” will be “the irreversible rate at which the world’s population is aging.”

Work shift

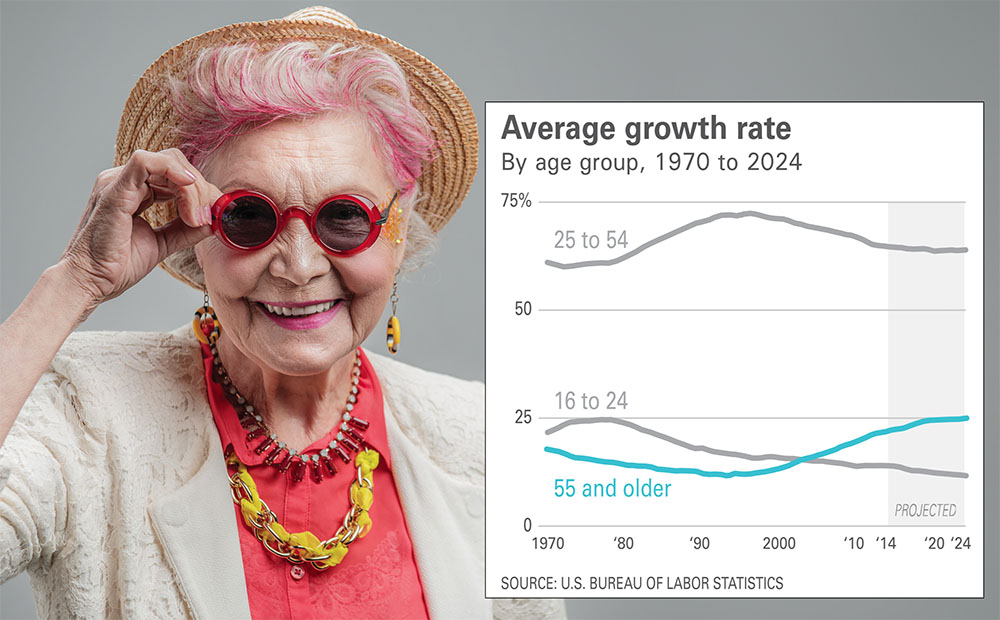

This societal shift will undoubtedly change work, too: More and more Americans want to work longer—or have to, given that many aren’t saving adequately for retirement. Soon, the workforce will include people from as many as five generations ranging in age from teenagers to 80-somethings.

Are companies prepared? The short answer is “no.” Aging will affect every aspect of business operations—whether it’s talent recruitment, the structure of compensation and benefits, the development of products and services, how innovation is unlocked, how offices and factories are designed, and even how work is structured—but for some reason, the message just hasn’t gotten through.

In general, corporate leaders have yet to invest the time and resources necessary to fully grasp the unprecedented ways that aging will change the rules of the game.

What’s more, those who do think about the impacts of an aging population typically see a looming crisis—not an opportunity. They fail to appreciate the potential that older adults present as workers and consumers. The reality, however, is that increasing longevity contributes to global economic growth.

Today’s older adults are generally healthier and more active than those of generations past, and they are changing the nature of retirement as they continue to learn, work, and contribute. In the workplace, they provide emotional stability, complex problem-solving skills, nuanced thinking, and institutional know-how. Their talents complement those of younger workers, and their guidance and support enhance performance and intergenerational collaboration. In encore careers, volunteering, and civic and social settings, their experience and problem-solving abilities contribute to society’s well-being.

In the public sector, policy makers are beginning to take action. Efforts are under way in the U.S. to reimagine communities to enhance “age friendliness,” develop strategies to improve infrastructure, enhance wellness and disease prevention, and design new ways to invest for retirement as traditional income sources like pensions and defined benefit plans dry up. But such efforts are still early stage, and given the slow pace of governmental change they will likely take years to evolve.

Companies, by contrast, are uniquely positioned to change practices and attitudes now. Transformation won’t be easy, but companies that move past today’s preconceptions about older employees and respond and adapt to changing demographics will realize significant dividends, generating new possibilities for financial return and enhancing the lives of their employees and customers.

Broadly, a longevity strategy should include two key elements: internal-facing activities (hiring, retention, and mining the talents of workers of all ages) and external-facing ones (how your company positions itself and its products and services to customers and stakeholders).

Let’s examine why leaders seem to be overlooking the opportunities of an aging population.

The ageism effect

There’s broad consensus that the global population is changing and growing significantly older. There’s also a prevailing opinion that the impacts on society will largely be negative. A Government Accountability Office report warns that older populations will bring slower growth, lower productivity, and increasing dependency on society. A report from the Congressional Budget Office projects that higher entitlement costs associated with an aging population will drive up expenses relative to revenues, increasing the federal deficit.

The World Bank foresees fading potential in economies across the globe, warning in 2018 of “headwinds from aging populations in both advanced and developing economies, expecting decreased labor supply and productivity growth.” Such predictions serve to further entrench the belief that older workers are an expensive drag on society.

What’s at the heart of this gloomy outlook? Economists often refer to what’s known as the dependency ratio: the number of people not typically in the workforce—those younger than 15 and older than 65—in a population divided by the number of working-age people. This measure assumes that older adults are generally unproductive and can be expected to do little other than consume benefits in their later years. Serious concerns about the so-called “silver tsunami” are justified if this assumption is correct: The prospect of a massive population of sick, disengaged, lonely, needy, and cognitively impaired people is a dark one indeed.

This picture, however, is simply not accurate. While some older adults do suffer from disabling physical and cognitive conditions or are otherwise unable to maintain an active lifestyle, far more are able and inclined to stay in the game longer, disproving assumptions about their prospects for work and productivity. The work of Laura Carstensen and her colleagues at the Stanford Center on Longevity shows that typical 60-something workers today are healthy, experienced, and more likely than younger colleagues to be satisfied with their jobs. They have a strong work ethic and loyalty to their employers. They are motivated, knowledgeable, adept at resolving social dilemmas, and care more about meaningful contributions and less about self-advancement. They are more likely than their younger counterparts to build social cohesion and to share information and organizational values.

Yet the flawed perceptions persist, a byproduct of stubborn and pervasive ageism. Positive attributes of older workers are crowded out by negative stereotypes that infect work settings and devalue older adults in a youth-oriented culture. Older adults regularly find themselves on the losing end of hiring decisions, promotions, and even volunteer opportunities. Research from AARP found that approximately two-thirds of workers ages 45 to 74 said they have seen or experienced age discrimination in the workplace. Of those, a remarkable 92 percent said age discrimination is very, or somewhat, common. Research for the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco backs this up. A study involving 40,000 made-up résumés found compelling evidence that older applicants, especially women, suffer consistent age discrimination. A case in point is IBM, which is currently facing allegations of using improper practices to marginalize and terminate older workers.

There’s more: Deloitte’s 2018 Global Human Capital Trends study found that 20 percent of business and HR leaders surveyed viewed older workers as a competitive disadvantage and an impediment to the progress of younger workers. The report concludes that “there may be a significant hidden problem of age bias in the workforce today.” It also warns that “Left unaddressed, perceptions that a company’s culture and employment practices suffer from age bias could damage its brand and social capital.”

The negative cultural overlay about aging is reinforced by media and advertising that often portray older adults in clichéd, patronizing ways. A classic example is Life Alert’s ad from the 1980s for its medical alert necklace, immortalizing the phrase “I’ve fallen, and I can’t get up!” Recent ads by E*TRADE and Postmates have also drawn criticism as ageist. A more subtle, but just as damaging example is the trumpeting of “anti-aging” benefits on beauty products as a marketing tool, suggesting that growing older is, by definition, a negative process.

Some companies are pushing back: In a recent video, T-Mobile’s John Legere took on the topic of ageist stereotypes while promoting a T-Mobile service for adults age 55-plus. He chided competitors for what he called their belittling treatment of older adults in marketing campaigns that emphasize large-size phone buttons and imply that boomers are tech idiots. “Degrading at the highest level,” Legere calls it. “The carriers assume boomers are a bunch of old people stuck in the past who can’t figure out how the internet works. Newsflash, carriers: Boomers invented the internet.”

Yet for the most part, employers continue to invest far more in young employees and generally do not train workers over 50. In fact, many companies would rather not think about existence of older workers all. “Today it is socially unacceptable to ignore, ridicule, or stereotype someone based on their gender, race, or sexual orientation,” points out Jo Ann Jenkins, the CEO of AARP. “So why is it still acceptable to do this to people based on their age?”

Over the past decades, companies have recognized the economic and social benefits of women, people of color, and LGBT individuals in the workforce. These priority initiatives must be continued—obviously, we’re not even close to achieving genuine equality in the corporate world; at the same time, the inclusion of older adults in the business diversity matrix is long overdue.

Patricia Milligan, senior partner and global leader for Mercer’s Multinational Client Group observes, “at the most respected multinational companies, the single class not represented from a diversity and inclusion perspective is older workers. LGBT, racial and ethnic diversity, women, people with physical disabilities, veterans—you can find an affinity group in a corporation for everything, except an older worker.”

Managing a multigen workforce

How can companies push past stereotypes and other organizational impediments to tap into a thriving and talented population of older workers? A range of best practices have been emerging and some companies are making real progress. Each points to specific changes companies should be considering as they develop their own strategies.

Redefine the workweek. To start, you need to reconsider the out-of-date idea that all employees work Monday through Friday, from 9 to 5, in the same office. The notion that everyone retires completely by age 65 should also be jettisoned. Companies instead should invest in opportunities for creative mentorship, part-time work, flex-hour schedules, and sabbatical programs geared to the abilities and inclinations of older workers.

Programs that offer pre-retirement and career transition support, coaching, counseling, and encore career pathways can also make employees more engaged and productive. Many older workers say they are ready to exchange high salaries for flexible schedules and phased retirements. Some companies have already embraced nontraditional work programs for employees, creating a new kind of environment for success. The CVS “Snowbird” program, for example, allows older employees to travel and work seasonally in different CVS pharmacy regions. Home Depot recruits and hires thousands of retired construction workers, making the most of their expertise on the sales floor.

The National Institutes of Health, half of whose workforce is over 50, actively recruits at 50-plus job fairs and offers benefits such as flexible schedules, telecommuting, and exercise classes. Steelcase offers workers a phased retirement program with reduced hours. Michelin has rehired retirees to oversee projects, foster community relations, and facilitate employee mentoring. Brooks Brothers consults with older workers on equipment and process design, and restructures assignments to offer enhanced flexibility for its aging workforce.

Reimagine the workplace. Your company should also be prepared to adjust workspaces to improve ergonomics and make environments more age-friendly for older employees. No one should be distracted from their tasks by pain that can be prevented or eased, and even small changes can improve health, safety, and productivity.

Xerox, for example, has an ergonomic training program aimed at reducing musculoskeletal disorders in its aging workforce. BMW and Nissan have implemented changes to their manufacturing lines to accommodate older workers, ranging from barbershop-style chairs and better-designed tools to “cobot” (collaborative robot) partners that manage complicated tasks and lift heavier objects. The good news is that programs that improve the lives of older workers can be equally valuable for younger counterparts.

Mind the mix. Lastly, you need to consider and monitor the age mixes in your departments and teams. Many companies will need to manage as many as five generations of workers in the near future, if they aren’t already. Some pernicious biases can make this difficult. For example, research shows that every generation wants meaningful work—but that each believes everyone else is just in it for the money. Companies should emphasize workers’ shared value. “Companies pursuing Millennial-specific employee engagement strategies are wasting time, focus, and money,” Bruce Pfau, the former vice chair of human resources at KPMG, argues. “They would be far better served to focus on factors that lead all employees to join, stay, and perform at their best.”

By tapping ways that workers of different generations can augment and learn from each other, companies set themselves up for success over the long-term. Young workers can benefit from the mentorship of older colleagues, and a promising workforce resource lies in intergenerational collaboration, combining the energy and speed of youth with the wisdom and experience of age.

PNC Financial Group uses multigenerational teams to help the company compete more effectively in the financial markets through a better understanding of the target audience for products. Pharma giant Pfizer has experimented with a “senior intern” program to reap the benefits of multigenerational collaboration. In the tech world, Airbnb recruited former hotel mogul Chip Conley to provide experienced management perspective to his younger colleagues. Pairing younger and older workers in all phases of product and service innovation and design can create opportunity for professional growth. And facilitating intergenerational relationships, mentoring, training, and teaming mitigate isolation and help break down walls.

To begin this process, start talking to your employees of all ages. And get them to talk with each other about their goals, interests, needs, and worries. Young and old workers share similar anxieties and hopes about work—and also have differences that need to be better understood companywide. Look for opportunities for engagement between generations and places where older and younger workers can support one another through skill development and mentorship. After all, if everyone needs and wants to work, we’re going to have to learn to work together.

To be clear, all of these changes—from flexible hours to team makeup—will require a recalibration of company processes, some of which are deeply ingrained. Leaders must ask, do our current health insurance, sick leave, caregiving, and vacation policies accommodate people who work reduced hours? Do our employee performance-measurement systems appropriately recognize and reward the strengths of older workers?

Currently, most companies focus on individual achievement as opposed to team success. This may inadvertently punish older employees who offer other types of value—like mentorship, forging deep relationships with clients and colleagues, and conflict resolution—that are not as easily captured using traditional assessment tools. Here, too, initiatives aimed at older workers can benefit other workers as well. For instance, research suggests that evaluating team performance also tends to boost the careers of employees from low-income backgrounds.

Turning a crisis into an opportunity

I’m admittedly bullish about the positive aspects of working longer and believe that company leaders can harness the opportunity of an aging population to gain competitive advantage. But I’m not oblivious to the challenges a longevity strategy poses. We’re talking about initiating a massive culture change for firms—a change that must come from the top.

But ignoring the realities of the demographic shift under way is no longer an option. CEOs and senior executives will need to put the issue front and center with HR leaders, product developers, marketing managers, investors, and many other stakeholders who may not have it on their radar screens. This will take guts and persistence: Leaders must bravely say, “We reject the assumption that people become less tech-savvy as they get older” and “We will fight the impulse to put only our youngest employees on new initiatives.”

To genuinely make headway on this long-range issue, companies will have to make tough, and sometimes unpopular, decisions, especially in a world where short-term results and demands dominate leaders’ agendas. But isn’t that what great leaders do?

The business community has a chance to spearhead a broad movement to change culture, create opportunity, and drive growth. In doing so, companies will improve not only mature lives, but lives of all ages, and the prospects of workers for generations to come. This transformative movement to realize the potential of the 21st century’s changing demography is the next big test for corporate leadership.

Excerpt: Paul Irving is chairman of the Milken Institute Center for the Future of Aging. He’s also author of the book, The Upside of Aging.