If she needs it, she has round-the-clock phone access to a home health care agency that can handle emergencies, bring in doctors and help residents navigate the medical system.

Though recent changes at the building clearly cater to seniors, the apartments also house young couples, working professionals and families. So living there doesn’t make her feel old.

“This is it,” Marky said, when asked whether she expects to leave Hummingbird Pointe, a 232-unit high-rise building on Ames Road. “They can’t get me out of here. I’ll go feet first-unless they get a tenant above my head that’s pounding at night.”

Forest City Enterprises, Inc.’s recent transformation of its aging Parmatown Towers community into Hummingbird Pointe is a nod to the region’s changing demographics. The need to house, and support, a rapidly aging population has huge implications for policy, planning and development in Northeast Ohio and across the state.

In 1990, 17.6 percent of Ohio’s population was at least 60 years old. By 2050, nearly 30 percent of Ohioans will be 60 or older, according to projections from the Scripps Gerontology Center at Miami University in Oxford. And nationwide studies show that the vast majority of older people want to stay put, if not in their houses, then in the communities where they have lived for years.

Marriages between health care groups and real estate operators aren’t uncommon. But Hummingbird Pointe is somewhat unusual. Forest City, a national real estate developer based in Cleveland, added services to a building that isn’t limited to older residents or part of a broader retirement community.

The common area at Hummingbird Pointe is part of a new, 14,500-square-foot addition that includes a hair salon, fitness facilities, events spaces and medical examination rooms. Local aging experts expect more innovation as real estate developers and landlords try to cater to-and capture-the region’s rapidly growing older population.

Local experts anticipate more such innovation, as developers try to attract and keep older residents and advocates push the idea of “aging in place.”

“This is an aging community, and we live in an aging county,” said Laura Matthews, manager of adult day services for Parma Community General Hospital. “We need to provide more support and options to let people stay in their home and in their community as long as we can. It makes sense not only financially, but socially. It’s something that we need to strive for.”

At Hummingbird Pointe, Forest City is wrapping up a $6 million makeover that includes renovated apartments and a 14,500-square-foot addition, with a new lobby, rooms for events and crafts projects, a garden, a cafe and the indoor pool that hosts classes like water walking.

The developer also brought in Infinity Home Health Services, a home healthcare agency, to provide renters with free access to an on-site nurse, to craft health and wellness programs and to bring doctors and physical therapists to see residents in the building’s two exam rooms. The amenities are available to all tenants, regardless of age.

“Anyone that comes in the door, if they make enough money to live here, we’re going to sign a lease with them,” said David Conway, VP of asset management for Forest City Residential Group. “We just believe that this is setting up for the next several years, that, naturally, the aging population is going to gravitate to this type of environment because they are health-conscious.”

For years, home builders have been experimenting with adaptable house designs meant to carry people from their 40s and 50s, into their 80s and 90s. In the 1990s, local hospitals experimented with placing satellite offices in apartment buildings and community centers. And some Northeast Ohio apartment buildings have added social workers, brought in speakers to talk about health or even spun off nursing homes as their residents aged.

“I think that we’re going to see more and more environments of a variety of kinds that are gearing themselves to serve the needs of seniors,” said Mitchell Schneider, president of First Interstate Properties in Lyndhurst. “Certainly in the multifamily arena, and even in other types of commercial development. I think everyone is thinking about the increasing number of seniors that will be a part of this population and making sure that commercial real estate is geared to support their needs.”

Andrea Ellison, a nurse and on-site wellness coordinator at Hummingbird Pointe, checks on a resident in one of the property’s examination rooms. Ellison works for Infinity Home Health Services, a local home healthcare agency that partnered with Forest City Enterprises to reposition the property and offers services to residents of other nearby Forest City apartment buildings.

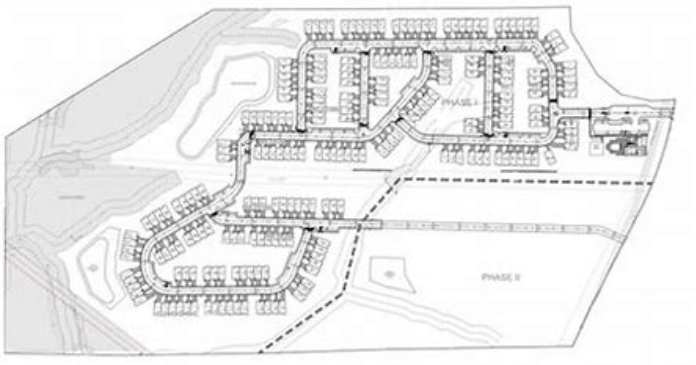

First Interstate owns the former Oakwood Club golf course property, including 90 acres and a clubhouse in Cleveland Heights. Schneider hopes to develop a continuing care retirement community, comprising 400 residences, on a portion of that land. The project is in early planning stages.

Continuing care retirement communities, such as University Circle’s Judson and Breckenridge Village in Willoughby, provide residents with choices ranging from traditional houses and apartments to assisted living and skilled-nursing facilities. Such developments face significant financing hurdles, since they can cost anywhere from $80 million to $150 million to build and rely, to a degree, on potential residents being able to sell their homes before moving in.

But Schneider’s research shows a huge potential audience in the eastern suburbs. And he’s willing to hold the land, and wait.

Across the country, people also have formed what are known as naturally occurring retirement communities-buildings or neighborhoods where residents pool their resources to bring in services. One of the best known is Beacon Hill Village, a Boston community that grew from a grassroots cluster of people, 50 and older, to a nonprofit organization with nearly 400 members dedicated to caring for themselves.

“There are a lot of different models, basically built around the same concept that you integrate services in with the housing,” said Ron Hill, executive director of the Western Reserve Area Agency on Aging. “Housing isn’t enough to help someone age in place. They have a hard time accessing services without any help.”

At Hummingbird Pointe, residents choose the services they want-and don’t pay for what they don’t need, said Infinity co-owner Matt Volansky.

The home healthcare agency offers residents dental screenings, health lectures and wellness events at no cost.

Infinity’s on-site nurse, Andrea Ellison, takes blood-pressure readings and coordinates appointments with visiting doctors, from hospitals including Parma Community General. She makes sure residents have lists of allergies, emergency contacts and medical issues where emergency professionals can find them.

Tenants who want more care, such as medicine management, pay for services individually. For an uninsured resident, it might cost $125 a month for daily help taking medicines. An Infinity fee schedule shows everything from a $5 visit for eye drops to an annual fee of $1,800 for once-daily assistance with diabetes and insulin.

The lobby of the Hummingbird Pointe property connects the new amenities center to the older high-rise building. Forest City is wrapping up a $6 million makeover that includes renovated apartments. The building is 87.5 percent occupied and nearly 90 percent leased-back to prerenovation levels, after occupancy dipped during construction.

Forest City and Infinity describe their deal, a three-year agreement, as a collaboration. Forest City is not paying Infinity, but the healthcare agency now has access to roughly 1,200 Forest City-owned apartments in several buildings near Parmatown Mall. Ellison already hops between buildings.

By November, an Infinity office and waiting room will occupy a ground-floor apartment at Forest City’s Independence Place I building, an age-restricted property on Independence Boulevard, Conway said.

After renovating and renaming Hummingbird Pointe, Forest City was able to raise rents, which now range from $658 to $1,098 for new tenants. And the developer hopes to increase occupancy by luring in renters and providing existing tenants with reasons to stay.

The building is 87.5 percent occupied and nearly 90 percent leased-back to prerenovation levels, after occupancy dipped during construction.

Paula Rider and her husband, William, recently sold their 4,000-square-foot house in North Royalton and moved to a two-bedroom apartment at Hummingbird Pointe. They’ve purchased a lot in Brooklyn Heights and still plan to build a home there. But apartment living-a novelty-is growing on them.

Rider, who is 66, has added some of her books to the apartment building’s library and had her hair cut, colored and styled at the salon downstairs.

She and her husband, who is 82, never contemplated living in senior housing or a retirement community.

“We don’t consider ourselves old,” Rider said. “We like the younger people. That wasn’t even on the radar.”

Author: Michelle Jarboe McFee, The Plain Dealer