Better times might be just around the corner for apartment investors stressed by the highest interest rates in years.

Or interest rates could easily keep rising as federal officials try to smother price inflation.

The uncertainty is maddening to apartment investors. After more than a year of rate hikes, a number of them are on the brink of defaulting on their floating-rate loan payments. Others struggle to make development deals work. Potential buyers and sellers still deeply disagree over prices. And borrowers who need permanent loans still face interest rates that are high—and unpredictable.

Uncertainty could also weaken the fundamental demand for apartments just as hundreds of thousands new apartments open their doors this year. The point at which high interest rates trigger collapsing economic growth, job losses and potentially weaker demand for apartments is also… wait for it… uncertain.

All these uncertainties are forcing investors to plan for possibilities that they have no control over—even more so than usual. However, a growing number of multifamily pros are finding reason to hope.

“There is growing conviction that we are either at or nearly at peak all-in interest rates for multifamily properties,” said Jesse Weber, vice chairman of debt and structured finance for CBRE, working in the firm’s San Francisco offices.

We there yet? Fed still fights inflation

At least apartment investors know what they want to happen in 2023 and 2024.

“Every real estate professional hopes the Fed is done raising rates,” said Ben Kadish, president and founder of Maverick Commercial Mortgage, based in Chicago. “Everyone hopes that interest rates will come down in 2024.”

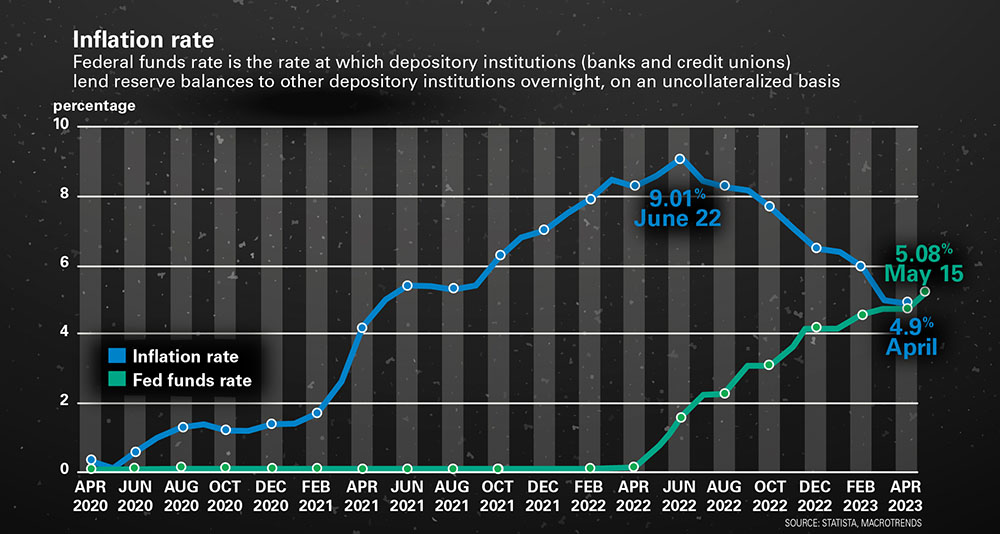

Federal Reserve officials already raised their benchmark, short-term, Fed Funds rate three time in the first five months of 2023. Each of those increases was just 25 basis points. That’s just a fraction of the big 75 basis point moves the Fed made last summer and fall.

Each increase adds to the burden on borrowers with floating-rate loans.

By May 2023, the Fed’s top target rate was 5.25 percent, up from just 0.25 percent at the beginning of 2022.

The Fed began raising interest rates to fight rising prices, throwing cold water on an overheated U.S. economy. One year later, the economic news has been… mixed.

“We expect the Fed will pause their rate hikes after this most recent increase,” said Matt Vance, Americas head of multifamily research for CBRE, working in the firm’s Chicago offices. “We expect rates to rise in the near term and to come back down slightly by year-end.”

In contrast, bond investors overall are betting federal officials have finished raising interest rates. They are paying prices that imply the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR)—the benchmark many floating-rate loans are based on—will fall over the rest of 2023 and keep falling to reach 3.0 percent by mid-2025.

“The forward SOFR curve suggests we are currently at the peak,” said Tony Nargi, managing director for JLL Capital Markets, Americas, working in the firm’s Denver offices.

Any developer who starts an apartment project this year will be forced to place their own bet on what officials at the Federal Reserve will do.

“It’s very difficult to understand the Fed’s outlook as it seems to change based on monthly indicators,” said Rich Ortiz, co-founder and managing principal at Hudson Realty Capital, based in New York City.

Despite a confusing outlook, developers started construction on new apartments at a seasonally-adjusted annual rate of 542,000, according to Census data. That’s nearly 200,000 more than the typical rate in the years before the pandemic.

Apparently, developers are willing to take the plunge despite high-interest rates, tough underwriting and low leverage.

“Construction financing is difficult, though possible,” said Evan Denner, executive vice president and head of business for Marcus & Millichap Capital Corporation, working in the firm’s New York City offices.

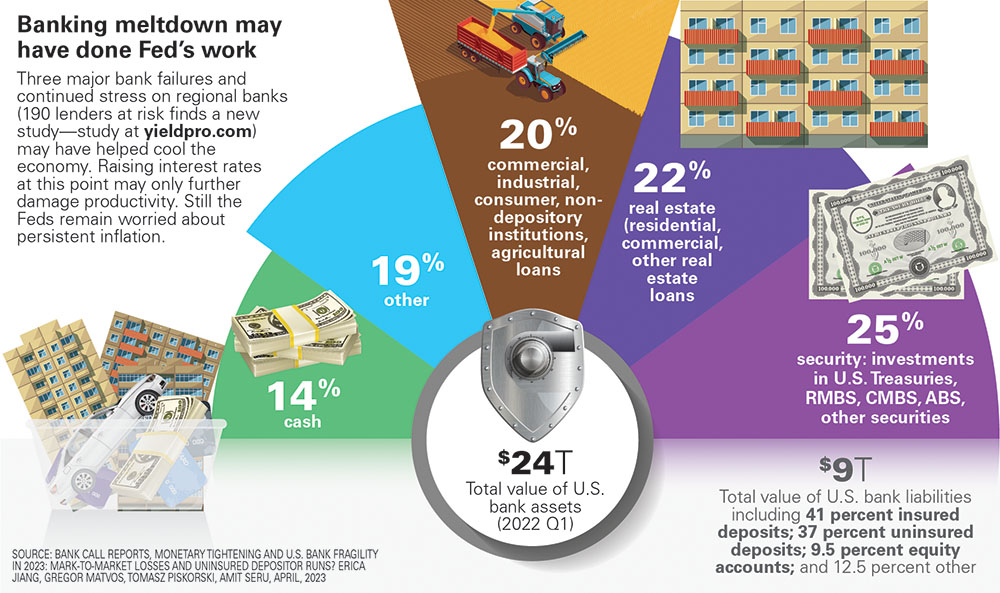

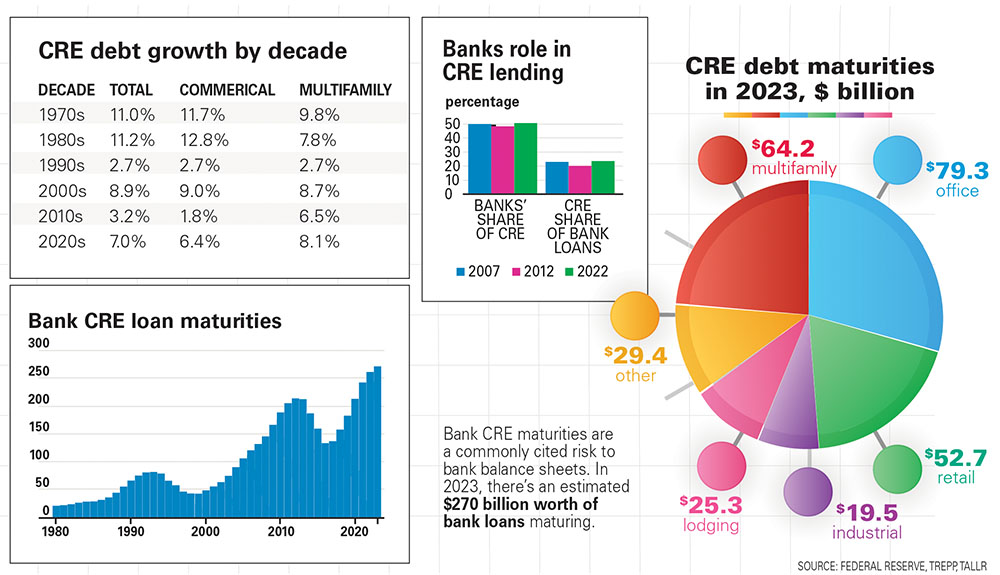

Banks have traditionally been the choice of many developers to provide construction loans to build apartments. Banks lenders were already much less willing to lend at the start of 2023 than they had been at the start of 2022, before interest rates rose. Banks have become even more careful after the failures of three big regional banks shook the financial markets—Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank.

“There are many fewer people out there offering loans,” said Doug Faron, co-founder and managing partner at Shoreham Capital, an apartment developer based in West Palm Beach, Fla. “We spoke to a lot of banks who said, ‘call us in six months and we might be back open for loans at that point.’”

Of the banks that are left, many still charge interest rates that float hundreds of basis points higher than the benchmark SOFR rate.

“Credit spreads have also increased by at least 100 basis points,” said Marcus & Millichap’s Denner. “All-in borrowing rates have gone from the 3.50 percent range to 9.50 percent for a typical construction loan.”

Many banks also require borrowers to take out recourse loans, which can allow a construction lender to claim assets from the borrower beyond the development if the loan defaults.

“Lenders are requiring higher net worth and liquidity benchmarks,” said Hudson’s Ortiz.

Developers also have to show strong demand for the apartments they plan to build. “When half of the lenders are no longer funding loans, the lenders that are active can be very choosy,” said Maverick’s Kadish.

Developers need to show that their projects are likely to earn enough rent to pay the interest on their loan—even if rents don’t grow much.

“Even in growth markets you are likely to see a slow-down and flattening or even a decline in rents,” said Shoreham’s Faron. “Positive leverage in this environment means that your project needs to have a development yield of 6.5 or 7.0 on an un-trended basis.”

In May 2023, Shoreham recently took out a new construction loan to build 400 apartments. The non-recourse loan will cover 55 percent of the cost, with an interest rate floating 325 basis points over SOFR.

“You are seeing what used to be a 65 percent or better leverage market is now a 55 to 60 percent leverage market,” said Faron. “That’s the world we are in: lower leverage and more expensive leverage.”

Developers have other options that may provide less onerous interest rates. “Life insurance construction-to-permanent loans and government backed programs such as HUD financing are notable exemptions, given their longer-term nature,” said Denner.

However, life insurance companies are notoriously choosy about whom they lend to, and HUD programs are also notorious for taking many months to close.

Bridge loans are also still available to borrowers interested in buying and improving apartment properties. The terms from banks tend to be similar to those now offered for construction loans.

“Most bridge loans are priced in the 400s over SOFR for all-in borrower rates over 9 percent,” said Denner. “Best in class assets and borrowers can receive rates as much as 100 basis points below this—but weaker borrowers in weaker locations with higher advance rates can be 100 basis points or more higher.”

Private equity debt funds charge higher interest rates with higher leverage. “The full rate is from 8.10 percent to 11.60 percent today, which are two to three times higher than two years ago,” said Maverick’s Kadish. “Leverage runs from 60 to 75 percent loan to value, down from 80 to 85 percent two years ago.”

Both bridge lenders and construction lenders are concerned about the permanent financing their borrowers will likely use to pay off construction loans, which also limits how much they are willing to lend.

“That causes each project to require much more equity,” said Kadish.

Permanent financing not getting any easier in 2023

Borrowers can still find permanent financing from a variety of lenders—at interest rates that are still much higher than borrowers had gotten used to in recent years.

“The permanent financing market is still functioning,” said Marcus & Millichap’s Denner.

Interest rates for new permanent loans made in the first five months of 2023 were still fixed just as high as the rates on offer at the start of 2023—sometimes spiking even higher.

Most permanent lenders offer loans with interest rates based on the yield of U.S. Treasury bonds. Rising wildly in 2022 from less than 2 percent to more than 4 percent, the yield on 10-year Treasuries mostly stayed between 3.4 percent and 3.6 percent for the first five months of 2023—though the benchmark swelled back towards 4 percent in February and early March.

“Treasuries reached a year-to-date peak in March, rendering many refinances and acquisitions unviable,” said Marc Gordon, principal, co-president and chief financial officer for Investors Management Group, working in the firm’s Los Angeles offices. “Rates subsequently dropped making those transactions viable again.”

The interest rates on offer for permanent loans are not as high as the floating rates of construction financing—which have ratcheted higher and higher since the start of the year. That’s some relief for borrowers who are finally ready to pay off floating rate loans. But it is a bad sign for the overall economy and demand for apartments.

When short-term interest rates are higher than long-term rates, it means bond investors see risk in the immediate future. Loan underwriters are paying attention, looking skeptically at even modest projections that rents will grow in the near term.

To find a loan with these high interest rates, borrowers can choose from a wide range of lenders. Agency lenders, life companies and CMBS lenders are all available.

“Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are very active for apartments,” said Maverick’s Kadish.

An apartment property that might have been offered an interest rate fixed at 4 percent by an agency lender in early 2022, will now have to pay 5.5 percent to 6.0 percent for a smaller loan, said Kadish.

“Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are active with a focus on workforce housing and affordable housing properties,” said CBRE’s Weber.

Life companies may still offer slightly lower interest rates than agencies, though they have become very conservative.

“While life companies are being selective, they are aggressively pursuing deals in markets they like and with strong operators,” said CBRE’s Weber.

CMBS lenders charge all-in interest rates around 6.5 percent and private equity debt funds charge even higher interest rates.

“Debt funds are challenged to find loans that can pay the high interest rates,” said Kadish.

Banks failures have also removed a few lenders from the market for making permanent loans.

“Signature Bank and First Republic Bank were each a material player in lending on small to mid-sized multifamily in coastal markets,” said Denner. Many other small and regional banks have limited new real estate lending to very low-leverage loans, very-well capitalized borrowers and borrowers with large deposits in the bank, or all three.

“Any deal you want to do right now, no matter how compelling, is harder to do than it was before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank,” said Faron. “There is a feeling of let’s wait and see, let’s preserve our capital for the disruption to come.”

High interest rates are digging holes into many project budgets

Some developers have been forced to stop building because they ran out of funds. Other investors have finished work on a new or rehabilitated apartment building—but need more equity to pay off their construction loan and refinance with a new permanent loan.

“It is more difficult to size to a cash neutral or better refinance,” said JLL’s Nargi. Some borrowers can afford to contribute more equity themselves. Others are looking to outside investors.

In more extreme cases, some overleveraged owners are being forced to sell or default. “More and more are trying to transact—that’s what we see, more opportunity in the space,” said Eric Brody, founder and principal of ANAX, based in New York City.

ANAX has partnered with private equity to bring new capital to these deals. “People are realizing that they are not going to be able to hold on for another two, three, four years,” say Brody.

“It’s important to get some wind into the sails of these properties to get them to the end.”

Author Bendix Anderson