The Colorado River Compact

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 divided the river into two basins: The Upper Basin (Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming) and the Lower Basin (Arizona, California and Nevada), established the allotment for each basin and provided a framework for management of the river for years to come.

The Compact remains a historic achievement. It was the first time in U.S. history that more than three states negotiated an agreement among themselves to apportion the waters of a stream or river. The Compact is the cornerstone of the “Law of the River,” which refers to the many compacts, federal laws, court decisions and decrees, contracts and regulatory guidelines that regulate use of the Colorado River.

Prior to the Compact, most of the Basin states were anxious about securing their share of the Colorado River but could not agree on how to allocate the river among themselves.

California’s growth was viewed with concern. The other states in the Basin feared California would establish priority rights to Colorado River water. Those concerns were intensified by a June 1922 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the law of prior appropriation—meaning whoever used the water first had first right of use in times of shortage—applied regardless of state lines.

The states proceeded to discuss an interstate compact to avert federal government intervention and avoid costly and time-consuming litigation. The Colorado River Commission was convened in January 1922 in Washington, D.C. with Herbert Hoover, then-Secretary of Commerce, as its chairman. The states, however, could not agree during that meeting on how to allocate the waters of the Colorado River Basin.

Delegates from the seven Colorado River Basin states met on Nov. 9, 1922, in New Mexico to discuss and ultimately work out the Compact, which was signed at the Palace of the Governors in Santa Fe on Nov. 24.

Terms of agreement

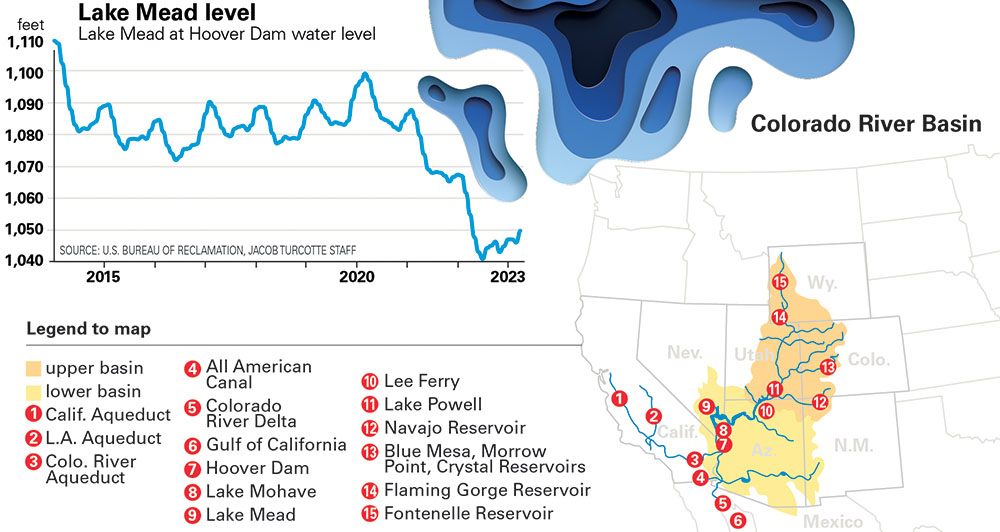

Based on Hoover’s suggestion, the Compact divided the river into Upper and Lower Basins with the division being at Lee Ferry, Arizona.

The Compact apportioned the right to exclusive beneficial consumptive use of 7.5 million acre-feet of water from the Colorado River system in perpetuity each to the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin.

This approach reserved water for future Upper Basin development and allowed planning and development in the Lower Basin to proceed.

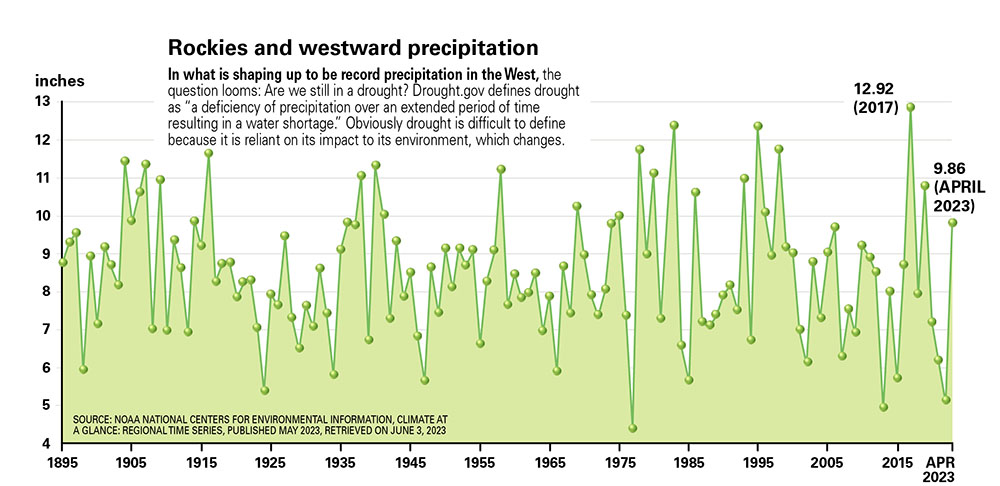

However, the allocations were based on hydrologic data that indicated annual Colorado River flow at Lee Ferry to be 16.4 million acre-feet. The figure was later revised to be about 13.5 million acre-feet. Furthermore, Colorado River flow fluctuates greatly from year to year, between 4.4 million acre-feet to more than 22 million acre-feet.

The Compact provides that the Upper Basin states will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre-feet for any period of 10 consecutive years. The Compact grandfathered irrigated water rights that were already in place on Colorado’s Western Slope.

The Compact’s only reference to Native American water rights is a single sentence stating that nothing in the document should be understood to affect the U.S. government’s obligations to tribal water rights.

Colorado River water for Mexico was addressed in the 1944 treaty between the U.S. and Mexico.

Although the 1922 Compact was signed by each of the seven Basin states, Arizona did not ratify it until 1944. Arizona had faulted the Compact for not allocating water directly to the states, instead of to the basins.

Specific allocations for each state were established later. The Lower Basin states were given their annual allocations in 1928 as part of the Boulder Canyon Project Act, which also authorized construction of what became known as Hoover Dam.

The annual allotments in the Upper Basin were established later by the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact of 1948.

Fast forward 2023

The states along the Colorado River—a vital source of water and electricity for the American West—reached an agreement with the Biden administration to conserve an unprecedented amount of their water supply in exchange for $1.2 billion in federal funding, state and federal officials said.

After nearly a year of negotiations and multiple missed deadlines, the deal is a temporary solution intended to protect the country’s largest reservoirs—Lake Powell and Lake Mead—from dropping to critical levels over the next three years. These reservoirs have fallen dramatically as the warming climate and the past two decades of drought have reduced the river’s natural flow by about 20 percent.

To stabilize the river, the three states that make up the Lower Basin—California, Arizona and Nevada—have agreed to voluntarily conserve 3 million acre-feet of water over the next three years, which amounts to 13 percent of these states’ total allocation from the river.

The Biden administration has committed to compensating the states for three-quarters of the water savings—or 2.3 million acre-feet—which would amount to about $1.2 billion in federal funds, those familiar with the talks said. The money from the Inflation Reduction Act would pay farmers, Native American tribes, cities and others who voluntarily forgo their supplies.

“There are 40 million people, seven states, and 30 tribal nations who rely on the Colorado River Basin for basic services such as drinking water and electricity,” Interior Sec. Deb Haaland said.

The deal was pushed along by the publication of the Interior Department’s environmental review of reservoir operations outlining two alternatives for how to distribute cuts in water usage among the Lower Basin states.

Neither of those alternatives were particularly palatable to the states, but nudged them toward compromise. The timing of that federal process also forced the issue, as the states had until May 30 to issue formal comments on the Interior Department alternatives.

As part of the new deal, Interior plans to suspend the comment period and instead analyze the new proposal in the federal environmental review process. The goal is to sign a record of decision that revises the 2007 rules that govern operations at both lakes.

Tom Buschatzke, Arizona’s commissioner to the Colorado River talks, emphasized that the deal did not represent a final outcome and that the parties have agreed to a new proposal to be analyzed by the Interior Department in the months ahead.

“It is important to note that this is not an agreement—this is an agreement to submit a proposal and an agreement to the terms of that proposal to be analyzed by the federal government,” Buschatzke said. “That is a really critical point for everyone to understand.”

Excerpt Water Education Foundation; Joshua Partlow, Washington Post