Millennials are now wealthier than previous generations were at their age. They can’t believe it either.

The median household net worth of older millennials, born in the 1980s, rose to $130,000 in 2022 from $60,000 in 2019, according to inflation-adjusted data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Median wealth more than quadrupled to $41,000 for Americans born in the 1990s, which includes the generation’s youngest members, born in 1996.

The turnaround has been so dramatic that millennials—mocked at times for being perpetually behind in building wealth, buying homes, getting married and having children—now find themselves ahead.

In early 2024, millennials and older members of Gen Z had, on average and adjusting for inflation, about 25 percent more wealth than Gen Xers and baby boomers did at a similar age, according to a St. Louis Fed analysis.

Ana Hernández Kent, a senior researcher at the St. Louis Fed and a millennial herself, spent years examining whether her cohort was a “lost generation.”

“They’re no longer lost,” she said. “They’re found.”

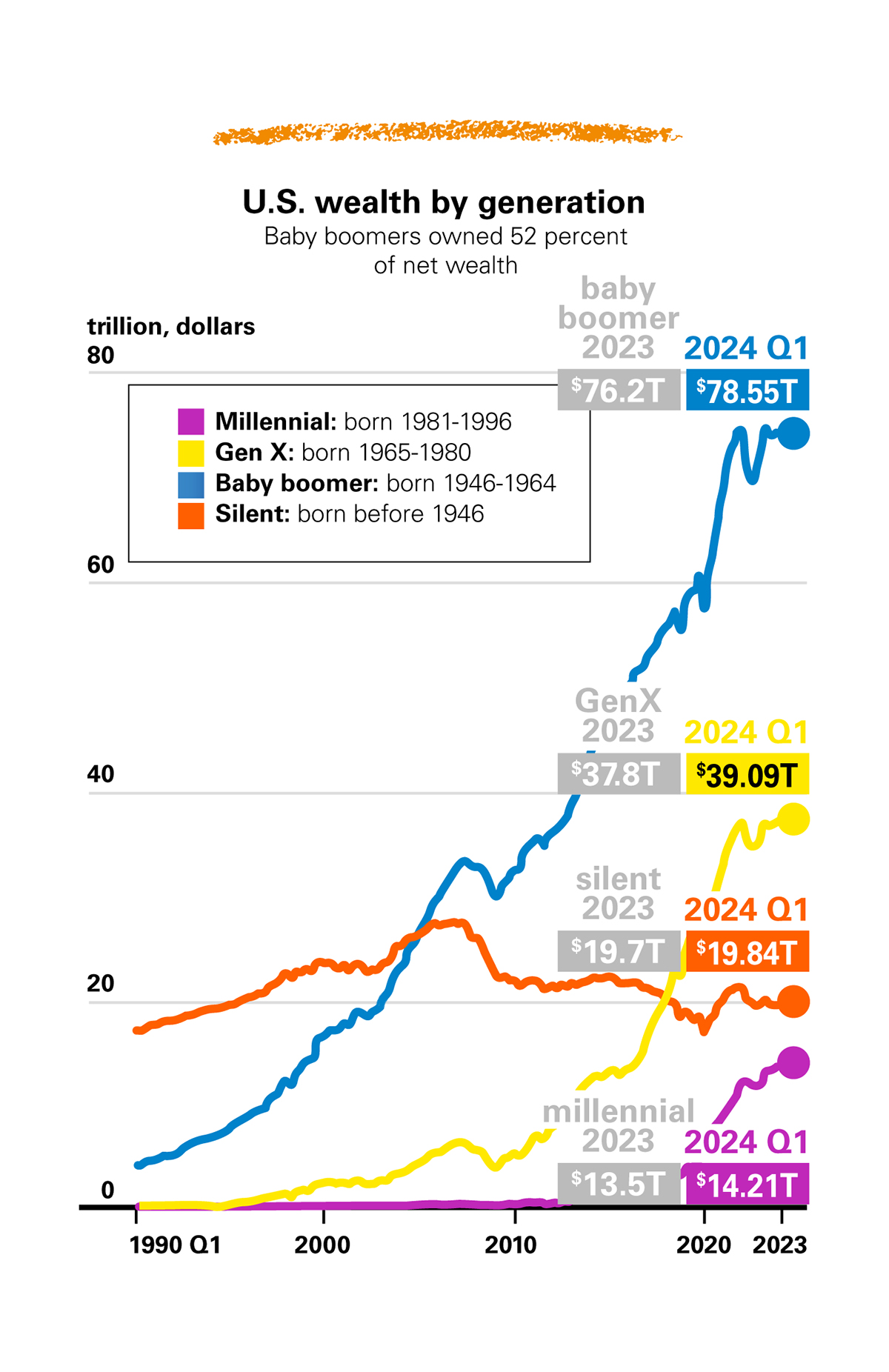

In the first quarter of 2024, the collective wealth of millennials and older Gen Z stood at $14.2 trillion, up from $4.5 trillion four years earlier, according to the Federal Reserve.

The biggest driver of that increase was real estate. Millennials’ housing wealth grew $2.5 trillion, after accounting for the additional mortgage debt they took on. A colossal jump in home prices benefited owners, whether they scraped together a down payment in the early 2010s or squeaked in just before the recent leap in prices and rates.

Stocks and mutual funds also played a key role, in part because many employees made larger contributions to retirement accounts earlier in their careers.

It’s unclear if millennials are better off overall, given the outsize increases in some of the most burdensome costs, such as childcare, housing and healthcare. They’re also projected to live longer than boomers, so they’ll need to make their money last.

As a group, though, they have traits that point to long-term prosperity, economists say. More have college degrees, which boost income. And they are having fewer children, which, whatever the effects on the country, is a boon to budgets.

Some 62 percent of millennials say vacations are a high priority in their household, compared with 54 percent of adults overall, according to Mintel, a market-research firm. They are also more likely to have paid for a luxury travel experience.

The generation’s approach to leisure is informed by witnessing the 2007-09 recession in their formative years, said Mike Gallinari, a senior analyst at Mintel.

“They realized they can lose their stuff to forces outside their control,” he said. “But nobody can take their memories from them.”

Phantom wealth

Overall, millennials hold about 9 percent of U.S. households’ wealth. That might seem small, but net worths tend to swell with age, meaning that increases work out to bigger percentage gains for younger generations that have yet to build up significant wealth.

Roughly 66 percent of Americans aged 30 to 44 said in 2023 they were doing at least OK financially, up from 55 percent a decade earlier, according to a Fed survey.

Gains in the value of a home or 401(k) can feel like phantom wealth because they are illiquid and have no bearing on day-to-day cash flow. Meanwhile, millennials are experiencing the weight of big-ticket items such as daycare.

They may also have memories of a parent losing a job during the 2007-09 recession, graduating college in a tough job market or, more recently, fumbling through the uncertainty of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Growing gaps

As successful as this generation has been overall, wealth inequality has widened among millennials compared with their predecessors.

The gap between the 80th percentile of wealth and the 20th percentile of wealth for millennials was about $343,000 in 2022, according to the St. Louis Fed. Adjusting for inflation, that gap was about $286,000 for boomers when they were a similar age in 1989.

One explanation is that the payoffs for white-collar work grew during that period, while those for working-class jobs stagnated, according to a 2023 study in the American Journal of Sociology. Another crucial divide: homeownership.

Older millennials’ homeownership rate recently caught up with that of previous generations, rising to around 60 percent between 2019 and 2022, according to the St. Louis Fed. Meanwhile, only about 39 percent of Americans born in the 1990s owned a home in 2022.

Black millennials are half as likely to own a home as white millennials, the largest gap of any generation, according to Redfin. Low-income Americans are also losing out. About 8 percent of new mortgages went to low-income buyers ages 25 to 34 in 2023, down from 9 percent in 2020, Redfin found.

Saving for a home and retirement feels like a far-off goal for many, especially millennials who aren’t high earners. It takes an annual household income of at least $100,000 to afford the median-priced home in nearly half of all metro areas, according to Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies. A job loss or medical bills can postpone the ability to save and buy a home even longer.

Strong foundation

Many who bought homes pre-pandemic are sitting pretty, even with rising insurance premiums and property taxes in some parts of the U.S.

“One of the biggest wealth divides, especially for millennials, is did you buy a house in 2020 or before, or after? Or not at all?” said Jean Twenge, a psychology professor at San Diego State University who has been studying generational differences for decades and wrote several books on the subject.

Existing home prices are up 19 percent adjusted for inflation nationwide since June 2020, according to the National Association of Realtors. The average home equity among owners with mortgages increased $122,900 over the past four years, according to CoreLogic.

Good timing

While soaring home prices play a large role in prosperous millennials’ finances, there are other factors working in their favor—high among them the rising value of retirement funds.

Millennials had an average 401(k) account balance of $59,800 in the first quarter of 2024 compared with $27,600 in 2019, according to Fidelity.

Good timing helped here, too.

Millennials were the first generation to have access to automatic enrollment in workplace plans during their early working years, said Matt Brancato, chief client officer in Vanguard Institutional Investor Group.

In 2006, 57 percent of employees aged 25 to 40 were enrolled in workplace retirement plans in which Vanguard was the record-keeper. In 2022, 83 percent were enrolled.

Vanguard estimates older millennials with median incomes will be able to replace almost 60 percent of their preretirement income with Social Security and savings from 401(k)s, individual retirement accounts and other sources. The youngest boomers with median earnings are, by contrast, likely to replace about half of their paychecks in retirement.