With 2024 soon in the rearview mirror, developers, operators and managers of apartments anticipate brighter days ahead for the multihousing industry. In hindsight, 2024 may be seen as the most challenging year for rental housing since the onset of COVID in 2020.

The Federal Reserve began a series of interest rate hikes in 2022 that still looms over owners’ ability to refinance debt. The unprecedented nationwide rent growth of 2021, which peaked at 15 percent in the first quarter of 2022, declined beneath the largest supply surge in 50 years, a surge that reached historic highs this year.

In the wake of the supply tsunami, developers struggle to stabilize newly delivered properties and contend with increased carrying costs and debt service payments on floating-rate loans after a spike over the last two years in the benchmark Secured Overnight Financing Rate, from near zero to around 5.3 percent.

This was also an election year fraught with financial and economic volatility. Rent control, a form of government-enforced price control that limits what property owners can charge for market-rate housing, was on the ballot again in several states and had mixed results at the polls.

It was also the year the Department of Justice sued RealPage and its clients, mostly apartment REITs and other large multifamily owners and operators, alleging its algorithmic pricing software contributed to widespread price fixing. RealPage provides tools to landlords and property managers to help them set rental prices, similar to other price-setting systems used by myriad industries around the globe.

Expense account

While supply has been the predictable headwind over the past year, and the easiest to forecast, expenses and property taxes are less predictable, said Jeremy Edmiston, executive managing director of Cushman & Wakefield’s build-to-rent division.

Expenses across the board continue to be a drain on owners’ net operating income, said National Apartment Association’s VP of Research Paula Munger.

All expenses, except utilities, are increasing faster than rents, according to the most recent Income/Expense IQ benchmarking data (based on 2023 financials). A same-store analysis reveals that total operating expenses for multifamily increased by 8.3 percent, while rents were up nationally by only 3.6 percent, she said. These expenses include property insurance.

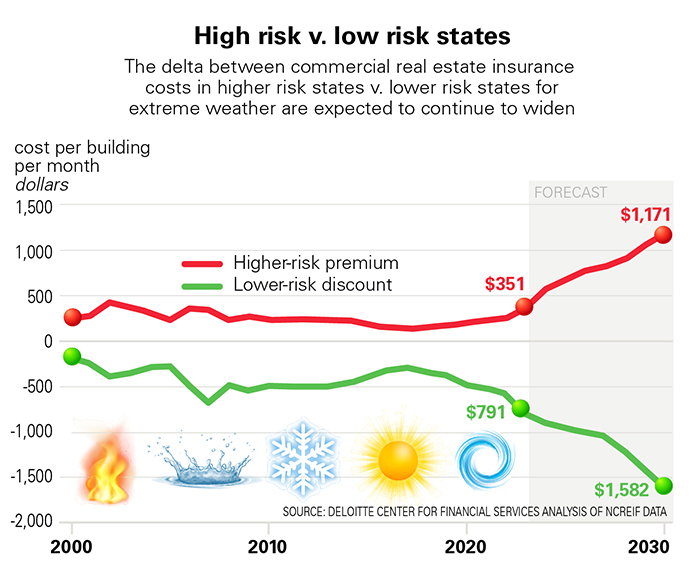

Extreme weather events drove multifamily property insurance rates up by an average of 12.5 percent annually between 2020 and 2023, hurting property values and causing some deals to sour. According to CB Richard Ellis, rising insurance rates have caused property values nationwide to decrease by 3.6 percent since Q4 2019.

NAHB VP of Multifamily Housing Dean Schwanke explained that increases in property insurance rates have the greatest impact on affordable housing. Unlike most market-rate landlords, affordable housing operators often must comply with rent caps, preventing them from defraying major new costs by raising rents, so they delay repairs or sell off assets instead.

According to a 2023 survey by NDP Analytics, more than 90 percent of affordable housing providers said they would need to adjust their operations to manage the increases in insurance costs, with more than half saying they would decrease or postpone investments in existing housing stock and new housing projects.

According to a 2023 survey by NDP Analytics, more than 90 percent of affordable housing providers said they would need to adjust their operations to manage the increases in insurance costs, with more than half saying they would decrease or postpone investments in existing housing stock and new housing projects.

“What’s happened in the property and liability insurance world is that many 300-year storm events happened within a short time window, giving insurers a great deal of exposure.

Costs have been trimmed back a hair this year, maybe even reaching a new normal, but in the last 30 days, we’ve had a new slew of events that impacted not just cost, but in high-risk areas like Florida, California, and Texas, are causing some underwriters to cash in their chips, put down their pencils and say, ‘I can’t write a policy right now for anyone,’” said Edmiston.

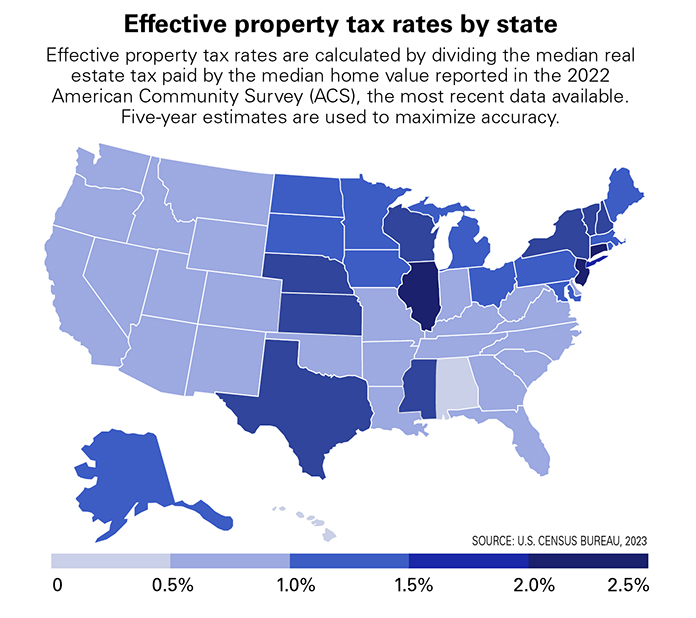

Property taxes are another operating expense that increased in 2023 and 2024. One issue is homestead exemptions that favor homeowners at the expense of apartment providers and residents.

According to the recently released “50-State Property Tax Comparison Study for Taxes Paid in 2023,” by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy and the Minnesota Center for Fiscal Excellence, homestead exemptions impact development and lead to rental housing providers and renters effectively subsidizing property taxes for homeowners.

Higher property taxes translate to higher rent to cover those expenses. “The average renter has a lower income than the average homeowner, and resultingly, preference given to homesteads relative to apartments introduces a regressive element into the tax system,” it says.

Despite this year’s headwinds, resilient demand and stellar absorption kept fundamentals from unraveling. Moody’s projects 2024 will end as the sixth-strongest demand/absorption year since 2000, while 2025 is projected to be the fourth-strongest year.

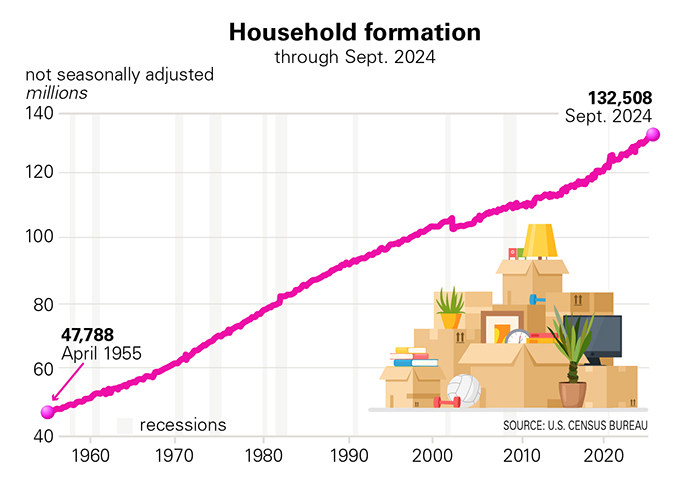

“Strong demand was a tailwind this year and as long as the economy stays on track, we can expect more household formation in 2025,” said NAA’s Munger.

Today’s strong demand resulted from a confluence of factors, including the strong economy, healthy job market, low unemployment, slowing inflation, improving consumer confidence, and wages growing faster than rents, said Jay Parsons, head of investment strategy and research at Madera Residential.

Nationally, the gap between new supply and demand is narrowing, although varying widely by market. Permits for multihousing projects were down 24 percent through September, while starts declined more than 30 percent, said Munger.

According to data from Yardi Matrix, the annualized rate of new construction starts dropped 50 percent from the levels recorded in 2022 and 2023 to around 325,000 this year.

Despite the steep decrease in starts, Yardi forecasts delivery of new apartments will remain robust next year at around 508,000 units, declining in 2026 to 372,000 units, bottoming at around the same number in 2027, before rebounding in 2028 and 2029.

Despite the steep decrease in starts, Yardi forecasts delivery of new apartments will remain robust next year at around 508,000 units, declining in 2026 to 372,000 units, bottoming at around the same number in 2027, before rebounding in 2028 and 2029.

“Most markets won’t see the impact of rapidly falling starts translating to lower completion levels until the second half of 2025, and more likely in 2026. This massive drawdown in starts across all regions sets the stage for a very different industry trajectory come 2026 and 2027,” said Doug Ressler, senior analyst and manager of business intelligence for Yardi Matrix.

With fewer new apartments coming online, competition for existing rental units will likely drive rent growth. “Although fewer starts will continue to help demand catch up to supply, it means we risk supply shortages again by 2026, a potentially major headwind,” said Munger.

In the pipeline

Meanwhile, seasoned developers like Thompson Thrift and Cushman & Wakefield continue to push projects forward despite high borrowing costs and market uncertainties. Some developers are adjusting their strategies for the coming years or shifting to markets with strong demand and job growth.

“Geographic diversification has been a tailwind for us as we move into markets where we see better opportunities. Some in the Midwest have held up better and have fewer deliveries,” said Paul Thrift, who with his partner John Thompson in 1986, purchased a repossessed home for $3,000, renovated and flipped it. They moved on to build fourplexes, student housing and market-rate apartments. Thompson Thrift’s current business model was developed in 2007.

“We develop three different multifamily prototypes that help us focus on controlling cost. Because our equity is privately funded through a high-net-worth network we’ve developed over several decades, we have access to markets many institutionally funded developers have not been able to start projects in. We have a strong conviction about starting our projects now. It’s based on the conventional wisdom that because of lower starts this year and predicted for next year, we’ll enter a period of lower deliveries in 2026, 2027 and 2028, and that will be an opportune time for us to deliver what we start today,” Thrift said.

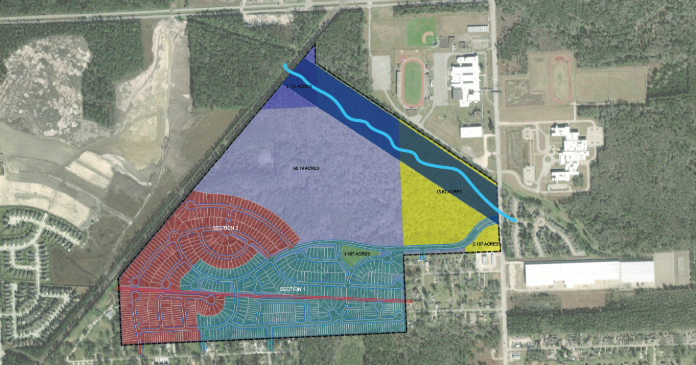

Cushman & Wakefield’s Edmiston sees the regulatory environment as a major challenge for build-to-rent developers in 2025 and beyond. In 2022, several local Georgia governments passed a first time-ever ban on build-to-rent subdivisions, a product Cushman & Wakefield is betting on for future growth. Pundits say this new regulatory approach is grounded in hostility toward outside investors and skepticism or prejudice against renters and must be fought against.

Cushman & Wakefield’s Edmiston sees the regulatory environment as a major challenge for build-to-rent developers in 2025 and beyond. In 2022, several local Georgia governments passed a first time-ever ban on build-to-rent subdivisions, a product Cushman & Wakefield is betting on for future growth. Pundits say this new regulatory approach is grounded in hostility toward outside investors and skepticism or prejudice against renters and must be fought against.

Build-to-rent arguably is the fastest-growing segment of the multifamily industry.

“A little more than five years ago, there was approximately just south of ten billion invested in the space in the U.S. Today, the number that has been raised and ready for deployment is approaching 100 billion,” said Edmiston, who was chosen in December 2023 to head his company’s build-to-rent division.

Some of the nation’s biggest landlords are piling into the build-to-rent space. AvalonBay Communities (AVB) entered the market in November with the $49 million acquisition of a townhome development near Austin, Texas, as part of the REIT’s strategy to expand in the Sun Belt and Mountain West markets.

AVB plans to make additional investments in build-to-rent communities to fill a gap in meeting resident needs between renting traditional apartments and homeownership.

Meeting tomorrow’s challenges

Another big challenge next year, said Edmiston, will be making project financials work so developers and builders can deliver the types of living spaces that we need to house Americans, whether it’s a for-sale home, a build-to-rent home, or traditional luxury, affordable or market-rate apartments.

“I think we will see labor and materials cost increases normalize year-over-year. But land and construction costs won’t come down, and the rates for 15-year and 30-year loans are not coming down, while the prices of single-family homes are still increasing. The average price of an existing home in the U.S. is still north of $400,000. This means renters can get a better deal on a 12-month lease than buying a home,” said Edmiston.

More good news for the rental housing industry is that households are forming all over the country in need of quality housing. Renter households are growing three times faster than homeowner households, based on a Redfin analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data going back to 1994. Renter households have formed faster than homeowner households over the past four quarters, while the cost of buying a home rose faster than the cost of renting during the same period.

“And that is another huge tailwind for multifamily,” said Edmiston.