In the week after President Donald Trump took the oath of office for the second time, the news was full of reports of raids on workplaces by federal agents, arrests of illegal immigrants, and new deportations to foreign countries.

President Trump promised mass deportations of 15 to 20 million illegal immigrants in his campaign for re-election. However, it’s still not clear how many people the government can detain, process and deport in four years—and what effect their removal might have on the apartment business.

So far, leading economists who study apartments have not included threatened mass deportations in their forecasts for 2025.

However, some apartment investors are expecting higher costs for construction labor as they plan for 2025. Many already struggle to find workers to build new apartment buildings.

“It can become a bidding war for labor,” said Vince DiSalvo, chief investment officer for Kingbird Investment Management, a real estate investment manager who invests in apartments nationally with offices in New York City. “Removing 1.6 million or 2 million or even 100,000 construction workers would be felt throughout the system at a time when construction budgets are tight and profit margins are low.”

Deportations, raids make headlines

Deportations, raids make headlines

Since Donald Trump returned to the White House January 20, the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has announced “targeted enhanced operations” and arrests of illegal immigrants in cities including Chicago, Boston and San Francisco. These raids were planned under the Biden Administration and carried out under the Trump Administration.

For example, on January 23, agents of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) surrounded Oceans Seafood Depot, a wholesale seafood distributor in Newark, N.J. The enterprise reportedly has 80 to 90 workers on a typical workday.

Three workers who could not produce identification were detained.

The federal agents did not present a warrant and questioned workers including a U.S. military veteran, according to Newark mayor Ras Baraka, who held a press conference about the event.

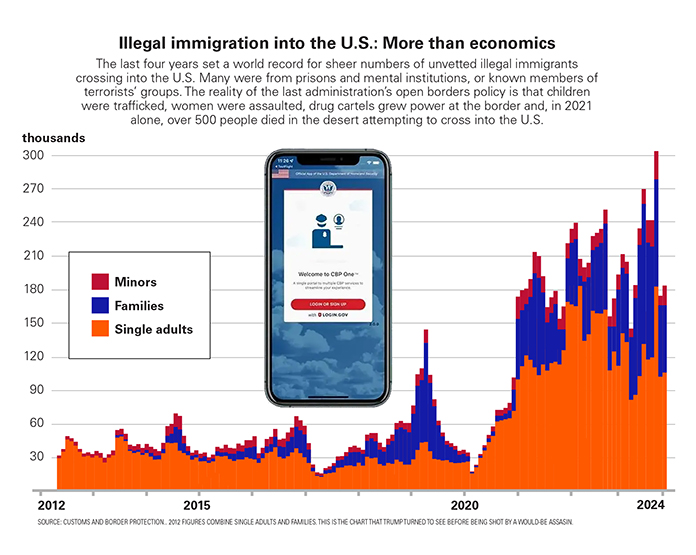

In the run-up to the 2024 election, President Trump told Time Magazine that he planned to deport between 15 million and 20 million people who he said are undocumented in the U.S.

“We take President Trump at his word. One of his many campaign points was immigration and the southern border—in particular in mass deportation,” said Jim Tobin, CEO of the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), based in Washington, D.C. “Nothing that we’ve seen so far surprises me about his effort to fulfill those campaign promises.”

Several organizations have estimated how many immigrants are illegally present in the U.S.

The most recent estimates range from 11.7 million (according to the Center for Migration Studies) to 13 million (Cato Institute) to more than 14 million (Center for Immigration Studies). For the number of undocumented immigrants to be much higher than 13 or 14 million, they would have to be much less likely than demographically similar people to do all the things academics counted to produce these estimates, such as commit crimes, give birth or die.

In addition, another 1 million people have applied for asylum in the U.S. and are waiting to have their cases decided. More than 1 million immigrants have been allowed to remain in the U.S. under Temporary Protected Status after disasters in their home countries—these include many of the Haitian immigrants living in Springfield, Ohio, who became famous in the presidential campaign.

Other immigrants are in the U.S. under a temporary program called “parole,” which has no relation to criminal justice which allows them to live and work for a time in the U.S.

Immediately after President Trump returned to the White House, he signed executive orders that may eventually result in the deportation of these immigrants.

That brings the total number of people who could be deported up to 15-to-17 million.

The effect of mass deportations on apartments

The effect of mass deportations on apartments

If millions of illegal immigrants were suddenly deported, they would leave behind a lot of empty houses and apartments.

“If you waved a magic wand and all illegal immigrants were removed from the United States, the demand for housing would fall,” said Alex Nowrasteh, vice president for economic and social policy studies at the Cato Institute.

Specifically, if roughly 13 million people were quickly deported, the U.S. population of 340 million would shrink by 3.8 percent.

The loss in population would shrink the U.S. economy by 4.2 percent to 6.8 percent, according to the American Immigration Council based in Washington D.C. The effects would be felt across the country, but most strongly in California, Texas, and Florida.

One of the biggest factors that determines the demand for apartments is whether the population in a market is growing or shrinking according to economists.

Historically, real estate values have tended to fall in places with declining populations, such as inner city neighborhoods such as the south Bronx in New York City in the 1970s and 1980s. Once households returned in the 1990s and 2000s, home prices recovered.

An immigration inflow equal to 1 percent of a city’s population is associated with increases in average rents and housing values of about 1 percent, according to a study by Albert Saiz, associate professor of urban economics and real estate at MIT.

In some submarkets or asset classes where immigrant renters are common, investors are preparing for a disruptive year. However, housing experts and economists are not preparing for the sudden deportation of millions of immigrants.

“It’s not probable,” said Brian Turmail vice president at Associated General Contractors of America. “We don’t subscribe to the worst-case scenario predictions.”

Neither, apparently, do the apartment economists at RealPage. They have not adjusted their forecast for the demand for apartments in 2025 since Donald Trump won election to account for the effect of promised mass deportations.

According to RealPage, the top factors that will affect the demand for apartments in 2025 include: slowing job growth, increasing wages, easing inflation, growing consumer confidence and rising prices for for-sale housing, which will continue to discourage renters from moving out of apartments, according to Carl Whitaker, chief economist for RealPage.

The impact of mass deportations does not even make Whitaker’s list. When asked, Whitaker declined to comment to the specific impact that changes in immigration policy could have on apartments.

“It’s very difficult to identify 13 million people who are here illegally,” said Cato’s Nowrasteh. “It’s even more difficult to apprehend them, detain them and try their cases and then it’s difficult to remove them.”

A one-time mass deportation operation that would remove 13.3 million immigrants without legal status would cost at least $315 billion, according to the American Immigration Council.

If the U.S. government were to instead invest in expanding the current infrastructure to a point where it could arrest, detain, process, and deport one million people a year, the total cost would balloon out to a total of $967.9 billion over the course of more than a decade, or $88 billion annually.

ICE currently has an annual budget of about $9 billion, and much of that is spent fighting global criminal networks and cross border crimes like human trafficking and fentanyl distribution. Congress could increase that budget. However, the Republican Party holds a very narrow majority—and several Republicans have committed to sharply cutting government spending, rather than increasing it.

ICE currently has an annual budget of about $9 billion, and much of that is spent fighting global criminal networks and cross border crimes like human trafficking and fentanyl distribution. Congress could increase that budget. However, the Republican Party holds a very narrow majority—and several Republicans have committed to sharply cutting government spending, rather than increasing it.

ICE currently has 20,000 employees, including support staff, according to ICE. Less than half of those employees are agents who can perform raids and detentions of illegal immigrants, said Nowrasteh. Many are already occupied in picking illegal immigrants from prisons after their sentences are complete and processing those people for deportation.

“The big bottleneck is personnel,” said Cato’s Nowrasteh. Theoretically, other government agencies or groups like local law enforcement could participate in raids to catch illegal immigrants. However, government agencies like ICE have historically resisted sharing their responsibilities.

Mass deportations will also require more immigration judges. In most cases, if a person is charged with an immigration offense, they cannot be deported without a hearing before an immigration judge, and the immigration court backlog currently stands at about 3.5 million cases.

When Barrack Obama was president, the U.S. often deported more 400,000 people a year. During President Trump’s first term and under President Joe Biden, the U.S. consistently deported more than 300,000 a year. Most of the people deported had been convicted of crimes and were turned over to ICE after their sentences were completed.

The first Trump Administration also performed raids to detain and deport illegal immigrants. In 2019, ICE raided several poultry processing plants in Mississippi. The raids caught about 700 illegal immigrants who were eventually deported. Those raids did not contribute significantly to the number of people deported in that year.

“Immigration raids are going to happen,” said Cato’s Nowrasteh. “They are going to be big. They are going to be showy. But they’re going to be exceptions to the general rule.”

Labor costs likely to rise

Threatened mass deportations are likely to make it more difficult and more expensive for developers to find labor to build apartments.

“We continue to face a persistent shortage of skilled labor in the construction sector,” said NAHB’s Tobin.

Nearly three-quarters (70 percent) of AGC members say they are having a hard time finding qualified workers, according to a recent AGC survey.

“Many of our members (contracting firms) tell us they’re not bidding on projects because they don’t have enough workers to do the work,” said Turmail. “If you don’t expand the workforce—if you actually shrink the workforce—it will make it harder to build things in this country. It will take longer to build things in this country and it will cost more.”

Developers depend on the labor of immigrants to build new apartments.

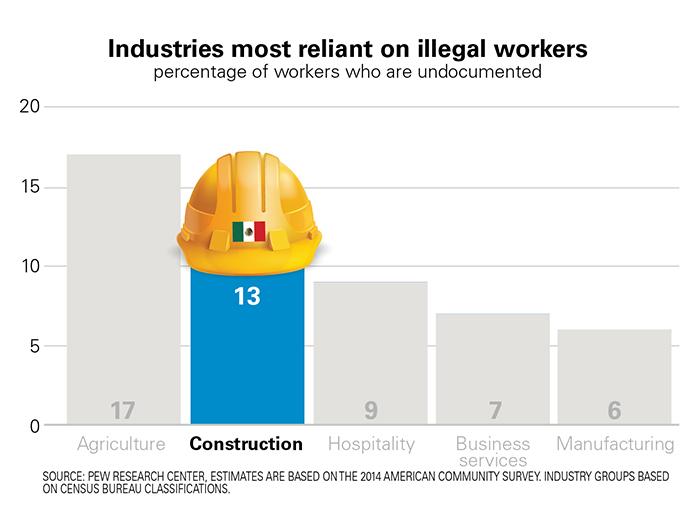

“One-third of construction craft workers—the folks you see out there with hard hats—are foreign born,” said Ken Simonson, chief economist for AGC. An estimated 13 percent of construction workers overall are undocumented, according to a report from the Pew Research Center.

Apartment companies and apartment investors may not be aware of how pervasive the immigrant labor force at their own properties, Simonson said. Apartment companies may carefully check the immigration status of workers they hire directly but rarely have access to the records of the contractors they bring to their properties.

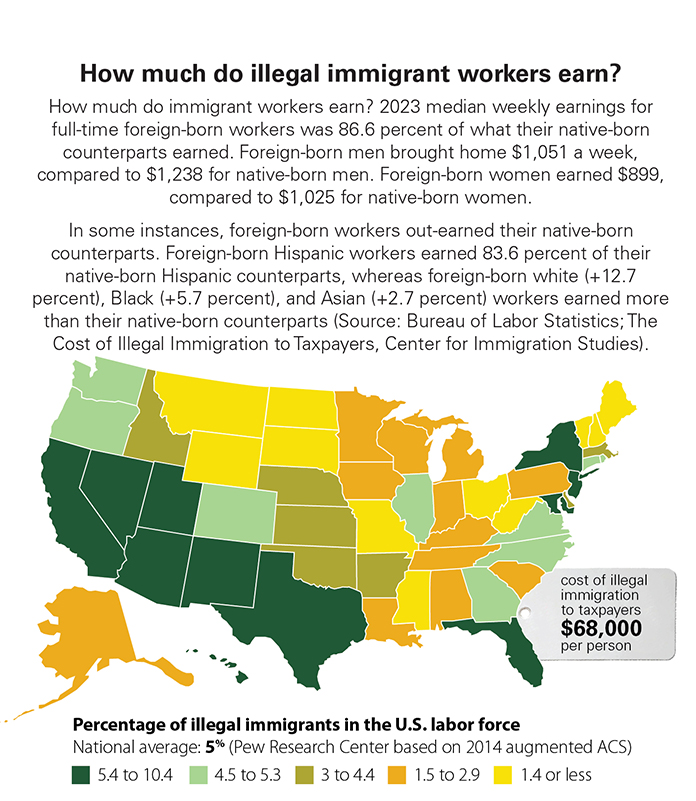

How many construction workers are foreign-born also varies widely by state—from a tiny fraction (1 percent) in Vermont to more than half (53 percent) in California, according to an analysis by economist Riordan Frost, senior research analyst for the Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies.

“We’re going to continue to need immigrant labor to work in the construction space until we train enough domestic labor to fill those holes—and that is a long-term, generational problem,” said NAHB’s Tobin.

Just the threat of deportation can reduce the number of foreign-born workers at the job site.

“Even the ones who are here with proper papers tend to make themselves scarce,” said Simonson “They may not have the papers with them or they may be worried about family members whose status may not be as clear.”

In the recent past—in 2022 and 2023, governors in Florida and Arizona made public statements that authorities could potentially visit job sites and arrest workers who could not prove that they were in the U.S. legally. Immediately after these announcements, AGC members reported that fewer laborers showed up to work.

Threatened mass deportations would have an even stronger effect. “Construction would suffer an immediate and probably long-lasting loss of employees,” said Simonson.

Developers are factoring threatened mass deportations into their plans for 2025.

“Immigration is one of a number of policies that we are keeping a close eye on—it has a profound effect on our industry,” said Kingbird’s DiSalvo. “It can have a profound effect on our industry if we see the most extreme versions play out.”

Kingbird plans to acquire apartments to renovate in 2025 rather than investing in ground up construction. The high cost of labor has been a factor in those plans.

“We already have shortage of construction workers,” said DiSalvo. “If we deport 1.6 million of them, you would just cause more strain and add more cost we would likely see an uptick in wage-driven inflation in the sector as a result.”

Industry groups like NAHB and AGC recognize that having millions of illegal immigrants create problems.

“Having a large pool of undocumented workers who status is tenuous is not ideal for the workers or for the economy,” said AGC’s Turmail. “That’s not the basis of a reasonable and responsible employer employee relationship.”

For example, workers worried about their immigration status may be less likely to complain if they are not paid properly.

“Anecdotally, our members tell us that they are getting underbid for projects by unscrupulous firms that are not properly paying the wages of their workers,” said Turmail.

“Our hope is that we take this moment on immigration and deportations and translate that into talking about comprehensive immigration reform,” said NAHB’s Tobin. NAHB has supported securing the borders and comprehensive immigration reform since 2009.

“Mass deportations don’t seem practical. So let’s see what the mechanism is where we can bring people out of the shadows and bring them into normalization,” said Tobin.

“We’re going to continue to need immigrant labor to work in the construction space until we train enough domestic labor to fill those holes—and that is a long-term, generational problem,” said NAHB’s Tobin.