The Loray Mill, which for decades produced fabric for car tires, in April began a $40 million conversion project that will create 190 apartments in its six stories, as well as several floors of shops and restaurants. The mill, which was the site of an famous labor strike in the 1920s, is in the city of Gastonia, a former industrial hub outside of Charlotte.

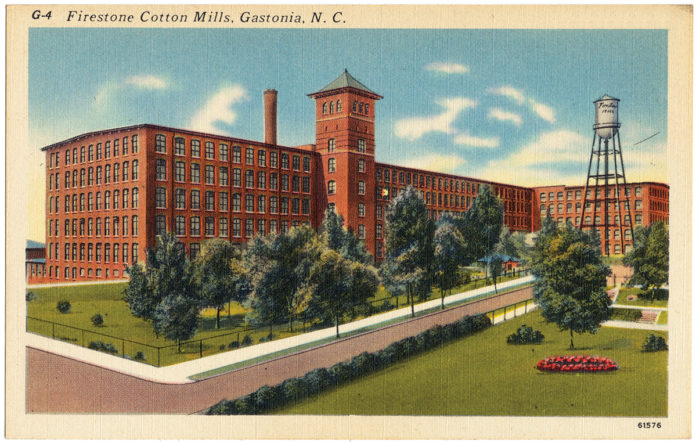

To the delight of preservationists, the development team of JBS Ventures, of Palos Verdes Estates, Calif., and Camden Management Partners, of Atlanta, will retain much of the original 600,000-sq.-ft. structure of the complex. This first phase of the redevelopment will reinvent about 450,000 sq. ft. of the mill, including the main section, which dates to 1902.

Gastonia officials, too, say there’s a lot to like about a project that continues decades of effort to remake a longtime industrial center as a bedroom community of Charlotte, which is just 30 minutes away. At the very least, they say that a redeveloped Loray (pronounced LOW-ray) could revitalize its immediate neighborhood, whose side-walk-lined blocks once bustled with mill workers but have long since grown quiet. The mill is on the west side of town in a primarily residential area where boarded-up buildings dot the main commercial drag.

“When you put this many apartments and businesses in an area where there’s been so much disinvestment, it’s enough to create its own weather,” said Jack Kiser, Gastonia’s senior executive for special projects. “It will have a catalytic effect.”

In many ways, the project, which is to be completed in 2014, is lucky even to be under way. Dozens of other mills, which went up in the central part of the state around the turn of the last century, as textile businesses relocated to North Carolina from New England, have fallen into ruin or been razed.

Loray Mill has seen several development proposals come and go since 1994, when Firestone, which had owned it since the Great Depression, shut the mill down and left for a more modern plant in a nearby community. Firestone has, however, continued some operations in a smaller building toward the rear of the property.

An early condo plan for the mill failed, and in the late 1990s, Firestone was poised to demolish the building, which features a 140-foot tower that is the tallest in Gastonia. But the company ultimately donated it to Preservation North Carolina, a nonprofit group, which paid its power bills and hired security guards while marketing the property, according to Myrick Howard, president of the preservation group.

“This was by far the most time-consuming project I have ever worked on,” added Howard, who estimated his group had helped save 700 buildings across the state since the 1970s.

In 2003, the current developers approached Preservation North Carolina about buying the property, with its arched windows and open floors lined with columns, but the team struggled to line up financing. Then, the recession hit, sapping public financing for the project and derailing efforts once again.

Today, Berkadia, a lender, is providing a $22 million loan backed by the Federal Housing Administration. Most of the balance is coming from two investors: Chevron, through federal preservation tax credits, and the health care provider Anthem Blue Cross and Blue Shield, which is taking advantage of state tax credits that encourage mill conversions.

The developers are also supplying equity, said Billy Hughes, a JBS principal, though he declined to specify the amount. The sale price of the mill was $660,000.

While the building’s industrial legacy may be part of its draw, it has also stoked some local opposition. In 1929, Loray was the site of a violent labor strike that lasted for months and resulted in two deaths, including that of Orville Aderholt, Gastonia’s police chief, and Ella Mae Wiggins, a union organizer and protest singer.

Even as leftover machinery was being removed from the mill in April, an older resident told Hughes the mill had tarnished Gastonia’s name and should be torn down, according to Hughes.

“This project has lived 1,000 lives,” said Hughes, whose previous development credits include the Johnston Mill Lofts, for which he also partnered with Camden. That 330-unit rental complex is in a former production facility for cotton fabric in Columbus, Georgia

The Loray project will take place in two phases. The first and larger phase will target the mill’s oldest part, which includes the tower. The 190 apartments will start at 1,000 sq. ft. each and will be spread across the top four floors.

The apartments will play up the mill’s industrial heritage, with exposed trusses on 16-foot ceilings, although concrete will be poured atop wood floors to muffle tenant footsteps, Hughes said.

Prices haven’t been set yet, but the nearby Armstrong Apartments, a recently redeveloped 1921 building with 18 units, rented its one-bedrooms for $600 a month and achieved full occupancy after only a few weeks of leasing this spring, according to Dewey Anderson, its developer.

The complex will also have 34,000 sq. ft. of amenity space, including a fitness center and outdoor pool. The retail spaces at Loray will occupy 79,000 sq. ft. on the bottom two floors. A market, dry cleaner and coffee shop will probably be among the 15 tenants, though none have signed up yet.

Loray will also have a 6,000-sq.-ft. public “memorial hall” with mill mementos, including looms, weaving machines and old photos, Hughes said.

A restaurant could be tucked into the tower, though “there really needs to be a synergistic fit for our residents,” said Hughes, who added that asking rents for the commercial spaces were still being determined.

Retail rents in Gastonia range from $12 to $20 a sq. ft., though that is usually for ground-level berths in strip malls on busy streets, unlike Loray’s setup, said Jerry Roche, owner of Centra Properties, a local commercial brokerage. The mill is on a quiet street of modest homes with open porches, although it does have plenty of parking in lots surrounding the property.

In the project’s second phase, the developer will focus on a 150,000-sq.-ft. wing built in the 1920s, with a renovation to cost at least $15 million. The ratio of homes to stores in this phase has not yet been set.

The property isn’t totally shedding its industrial past. Firestone will continue to coat its tire fabric in a low-slung 200,000-sq.-ft. building at the rear of the property, company officials said. Some apartment windows will gaze out at the complex, though a new 12-ft. wall will screen views from the pool deck, Hughes said.

What effect the new complex might have on the surrounding blocks is up for debate. Gastonia officials, citing their own research, say the neighborhood will benefit from about $330 million in new investment in the area, though that won’t come to fruition for three decades.

But others worry the mill’s somewhat isolated location could work against it. “The west side of Gastonia still has a long ways to go,” said Roche, the broker and a 28-year resident of the region.

Still, Roche said, most of the community is rooting for something to happen at a site that has long languished. “This is an important project for the city,” Roche said, “and we wish them the very, very, very best.”

Author: C. J. Hughes, New York Times