While soaring real estate prices and ludicrous rents have ceased being news in places called Pacific Heights or Park Slope, the dual tsunamis of gentrification that submerged both coasts are moving inland, threatening small and midsize U.S. cities where the idea of spending half of your pay on rent was once inconceivable. No more.

Since taking office, Barry has earmarked $10 million in city money to encourage the construction of affordable units and pioneered a program to donate vacant city-owned land to nonprofit developers. She also pushed the City Council toward a vote on what has come to be called “inclusionary” zoning. It’s a policy that requires developers to build units reserved for residents earning less than the median area income if they want permission to build higher-density projects.

The state legislature delivered a preemptive strike against Barry’s plan, recently voting to ban mandatory inclusionary zoning. On one level, the vote reflected the partisan clash between the city’s Democratic leadership and Republicans who dominate Tennessee’s legislature. (Two years ago, state legislators blocked the city’s plan to build a new bus system.) But the ban also reflects the delicate balancing act required to pass inclusionary zoning, a decades-old tool that has enjoyed renewed interest in recent years as cities seek to make affordable housing palatable to developers.

“We want to create mixed neighborhoods, avoid concentrating poverty,” said James Fraser, a professor at Vanderbilt University who has consulted on Nashville’s housing plan. That’s invited pushback from neighborhood groups that shun new affordable units, as well as from local developers. “They’re going to use the state legislature to try keep it from happening,” he said.

Created to meet two goals

Inclusionary housing emerged from the suburbs of Washington, D.C., in the early 1970s to meet two goals: Create affordable housing at low cost to local governments and mix housing reserved for low- and moderate-income residents with higher-priced rentals and for-sale units. The particulars vary, but the main idea was to tie the construction of housing for working-class households to market-rate projects. That often means granting a variance to build more units than zoning codes typically allow or offering tax abatements and other incentives.

About 500 local jurisdictions, from New York City to West Palm Beach County, Fla., have adopted these kinds of policies over the years. But now, as developers rush to build new, market-rate apartments in cities big and small, some local officials are considering inclusionary zoning for the first time, while others seek to add teeth to existing programs, said Erika Poethig, director of urban policy initiatives at the Urban Institute.

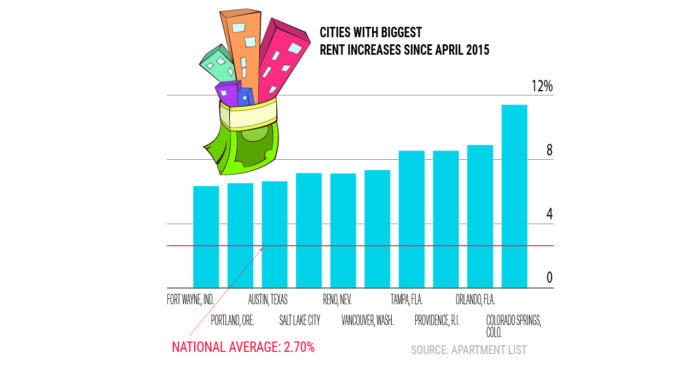

These moves come as local real estate markets continue to recover from a recession that caused construction to grind to a halt, constraining supply and driving up rents.

As new projects did come up, the first to move forward were designed to luxury specs, famously targeting a new breed of affluent city-dwellers on the coasts. Median gross rent, including utilities and adjusted for inflation, increased 6 percent from 2001 to 2014, according to the Center on Budget & Policy Priorities; median renter household income fell 9 percent.

If rents continue to rise faster than pay, 15 million Americans could be spending half their income on rent by 2025, according to a report last year.

Contentious policy

Earlier this year, the Oregon legislature overturned the state’s 17-year-old ban on inclusionary zoning with strong backing from Portland officials. A June ballot measure will give San Francisco voters a chance to increase from 12 percent to 25 percent the share of affordable units that developers must include in market-rate construction. And in November, Los Angeles voters will decide whether to require developers who seek zoning changes to dedicate as much as 20 percent of all units to affordable housing.

New York City, which passed a beefed-up inclusionary-zoning policy in March, might provide a case study on how contentious the policy can be. Mayor Bill de Blasio sought to make 30 percent of new units affordable to residents earning less than the area median income. That ambitious plan triggered opposition from housing activists, who said the new units would end up being unaffordable to many renters. The local business community meanwhile complained that lowering income levels would make the program more expensive for developers, leading to the construction of fewer units over all.

In Atlanta, where Mayor Kasim Reed proposed setting aside 10 percent of units in new residential buildings for affordable housing, there are a different set of obstacles. Philip Tague, president of developer AMLI Residential, said most local builders think inclusionary zoning will depress land values by limiting income from new projects. Meanwhile, there’s not enough demand for higher-density zoning to make the horse trade worthwhile, especially since there are good building sites in suburban counties outside Atlanta.

Fostering a diverse mix of residents makes for better neighborhoods and cities, said Tague: “If you’re a long-term owner of real estate, that’s a net positive for you.” He added, however, that he thought Reed’s plan is a long shot.

Source: Bloomberg News