“Apartment demand surged in second quarter,” says Greg Willett, chief economist for MPF Research, a division of Real Page Inc. “Strong demand pushed occupancy back to the post-recession peak.”

A string of bad news headlines shook world financial markets at the beginning of the year. Demand for apartments also weakened in the first quarter, according to firms like MPF, while developers prepared to open hundreds of thousands of new apartments. Strong demand for apartments in the second quarter eased some of those worries. Economists still agree that the number of vacant apartments is likely to rise, but the overall demand for rental units continues to be stronger than the supply.

“The fundamentals of the multifamily industry are very strong,” says John Sebree, director of the national multihousing group with brokerage firm Marcus & Millichap.

However, the divide continues to widen between new, luxury apartment communities where some managers now offer concessions to lure renters and less expensive, class-B apartment communities that are fully occupied with long waiting lists.

Vacancies still very low

Top research firms now disagree about exactly where the vacancy rate is for apartment properties. According to MPF, strong demand for apartments pushed the percentage of vacant apartments in the U.S. all the way down to 3.8 percent in the second quarter, its lowest level since before the Great Recession. That’s down from 4.3 percent in the first quarter.

The percentage of vacant apartments has been much less volatile according to the data tracked by research firm Reis Inc. In the second quarter, 4.5 percent of apartments were vacant, on average. The vacancy rate has been rising steadily and very slowly from its low point of 4.2 percent in the second quarter 2015, according to Reis. “For the fifth consecutive quarter new construction exceeded net absorption, indicating that demand cannot keep pace with such a large construction pipeline,” says Ryan Severino, senior economist and director of research for Reis.

Researchers at both firms agree, however, that the vacancy rate is still very low, and is likely to rise as developers open more new apartments. “Occupancy is likely to dip a little bit because so much new supply will be moving through initial lease-up,” says Willett. However, demand for those apartments continues to be very strong. “Demand is not faltering.”

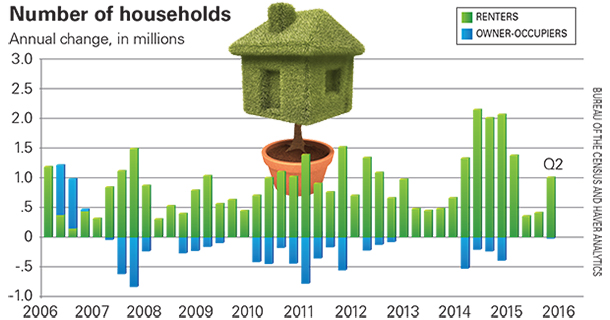

Most of the demand for new apartments comes from the formation of new households that need places to live, says Sebree.

The number of new households has been growing more quickly as the U.S. economy continues its slow, steady recovery. Over the last seven years, the number of households in the U.S. grew by an average of 1.0 to 1.1 million a year. Last year, the number of households grew by 1.33 million. This year, the number of households is anticipated to grow by 1.43 million. “That’s 300,000 more than the average,” says Sebree.

All of those new households will need homes—and developers aren’t building enough to meet the demand. Developers are planning to create 1.1 million units of housing in 2016, including 285,000 multifamily units and 800,000 single-family units. “If that is true, we are still short of increased demand by more than 300,000 dwelling units,” says Sebree.

The widening divide between Class-A and Class-B

The challenge for property managers is that some of these new households can’t afford the expensive new apartment properties now under construction.

“Much of this demand is coming not in class-A-quality product but class-B and class-C quality,” says Sebree. Most the new apartments opening are class-A units. The mismatch has pushed the percentage of vacant class-A apartments to an average 6.1 percent in the second quarter, up from 5.2 percent in 2012.

“There are certain markets where class-A vacancy in higher, and leasing is taking longer than anticipated for new projects,” says Sebree. “Some new construction properties reportedly offer some concessions in competitive markets that have an especially high number of new units.”

In contrast, the percentage of vacant class-B and class-C apartments fell to an average of 2.7 percent in the second quarter, down from 5.2 percent in 2012, according to Marcus and Millichap. “In most places, resident prospects are lined up to rent any class-B stock that becomes available, and shortages of class-C product exist in select spots, too,” says Willett.

That means the managers are keeping a close eye on their renters, as they consider raising the rents. “People can only afford to spend so much,” says Sebree. “Managers are cautious on how much to raise rents.”

Overall, rents grew 4.6 percent over the 12 months that ended in the second quarter, according to MPF. Reis found a similar 4.0 percent increase in both asking and effective rents. “Average annual rent growth has slowed modestly from this economic cycle’s peak growth of 5.6 percent, seen in the third quarter of 2015,” according to MPF. “Annual rent growth in the range of 4.0 to 5.0 percent is an unprecedented result six years into a growth cycle,” says Willett.

“I think rent growth across all sectors will continue to be good, though not as great as it was from 2013 to 2015,” says Sebree.