A growing number of states in the U.S.—and countries around the world—are legalizing or decriminalizing recreational and medical marijuana, forcing businesses to grapple with how to deal with employees who use the drug and could come to work still feeling its mind-altering effects.

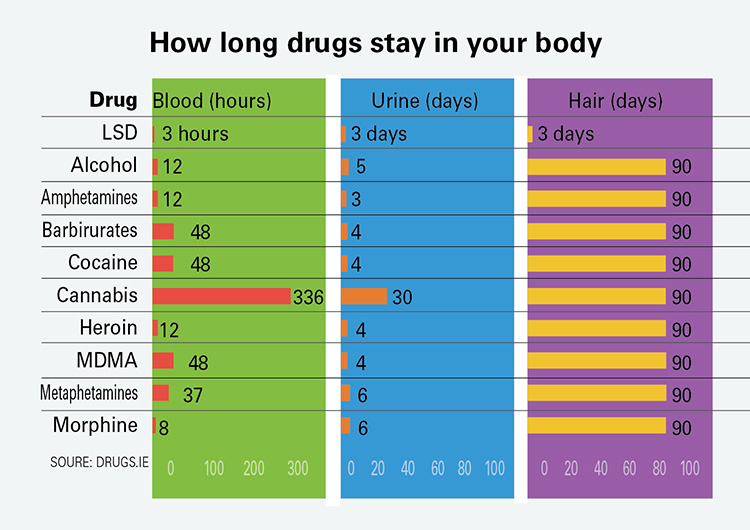

But unlike alcohol or many other drugs, marijuana stays in a person’s system for weeks or months after usage, which creates a tricky situation for workplace drug tests. It’s entirely possible that employees could use marijuana in their personal time in a state or country where it’s legal to do so—and be fired for testing positive on a drug test when they’re back at work days or weeks later.

The proliferation of different, sometimes conflicting laws and policies on marijuana use is especially vexing for companies operating across the globe—or even just in multiple states within the U.S.

In the U.S., marijuana is illegal under federal law, but 30 states and the District of Columbia have legalized it for medical or recreational purposes. More than 20 percent of American adults use marijuana and 14 percent do so regularly, according to a survey this year by Yahoo News and Marist College in Poughkeepsie, New York. And marijuana use is expected to jump significantly over the next few years in North America. Voters in California, by far the largest state with nearly 40 million residents, legalized recreational marijuana last November. Meanwhile, Canada is poised to legalize cannabis for recreational purposes next year. (Both California and Canada long ago legalized the drug for medical treatment.)

Marijuana use, however, is still illegal in many countries, including the U.K., France, Ireland, Indonesia, China, Japan, South Korea and Saudi Arabia. But personal use in varying quantities has been decriminalized in such countries as Italy, Mexico, Argentina, Austria, Chile, Colombia, the Netherlands, Spain and Switzerland, while medical use of the drug is legal in many countries, including Australia, the Czech Republic, Germany and Turkey. Uruguay became the first country to fully legalize the production and sale of recreational marijuana. Pharmacies now sell the drug there.

“You almost need counsel in each country you operate in so that you set up a workplace drug policy that won’t violate that country’s laws,” says Tony Fiore, a lawyer at Kegler Brown Hill & Ritter in Ohio.

Patchwork laws

Some U.S. laws and court rulings permit companies to arbitrarily fire employees who test positive for marijuana in states where it’s now legal. For example, the Colorado Supreme Court has ruled that employers can fire workers who test positive for cannabis even when they’re using if for medical reasons. Because marijuana remains illegal under federal law, the court upheld the firing of Brandon Coats, a quadriplegic telephone customer service representative at Dish Network who was using the drug to treat painful muscle spasms and tested positive in a random test.

According to court records, he wasn’t accused of being under the influence or impaired at work, and he said he never used weed while in the office. Coats had worked at Dish for three years and received satisfactory performance reviews before his termination in 2010. He didn’t perform any hazardous activities at work and never requested accommodations for his medical marijuana use.

Other U.S. states have enacted laws that require employers to try to make accommodations for people using weed to alleviate pain or for other health reasons—as long as the drug doesn’t affect their performance in the workplace.

Drug testing practices and laws vary widely across the globe. The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that only Finland, Ireland and Norway have legislation specifically addressing drug testing in the workplace. In Norway, for example, drug testing is considered a violation of the personal integrity of an employee or job applicant and should be conducted only when strictly necessary, such as to protect the safety of the worker or other people.

Canadian employers generally have much less freedom to conduct drug tests than U.S. businesses. “Pre-employment testing isn’t typically allowed and most employers can’t do random testing either,” says Darryl Hiscocks, labor and employment lawyer at Torys LLP in Toronto. “Employers often feel caught in the middle. They have to meet their health and safety obligations such as with workers who may drive a vehicle, but they also have to accommodate medical marijuana users and employees addicted to marijuana, which can be considered a disability.”

He believes that businesses should ask employees to inform their managers if they are using marijuana to treat a health problem and provide their prescription. “It’s a matter of balancing employee privacy interests and human rights with workplace health and safety concerns,” Hiscocks says.

Because of the patchwork of laws, employees who rely on marijuana for health reasons or are regular recreational users may face limited career prospects. “Their opportunity to move may be eliminated if they’re authorized to use medical marijuana in one state, but it isn’t allowed in another state or country,” Fiore says. “It also would hurt the employers, who couldn’t transfer some workers and their needed skills overseas.”

Complex and changing issue

There are no statistics on how many people have been fired—or not hired—because of testing positive for marijuana use, but there’s no question that it is happening. “Marijuana in the workplace is a complex issue that will only require greater attention from employers as more states and countries decriminalize it,” says Todd Simo, chief medical officer at California-based HireRight, which provides background-screening services to businesses. “A positive marijuana screen is now a yellow light, not a red light as in the past.”

Marijuana use usually isn’t permitted in jobs that could pose safety risks, such as driving a bus or operating heavy machinery. What’s more, businesses with US government contracts are supposed to follow federal law and fire or refuse to hire people who test positive for marijuana and other drugs.

“The situation with marijuana is changing almost weekly,” says Sarah Sullivan, risk control services coordinator at Lockton, a Missouri-based insurance broker and professional services firm. “The important thing is to protect yourself with a workplace policy that explicitly says whether you will or won’t be testing people.”

Despite growing decriminalization, many employers have failed to create a marijuana policy, let alone tailor it to different states and countries. Slightly more than half of respondents said they don’t have a policy, according to a 2016 HireRight study in the US. Nearly 40 percent said they don’t accommodate employees who use marijuana and have no plans to do so, while 5 percent said they do have a policy to accommodate marijuana use, and 5 percent said they may make accommodations within the next year.

Talent shortages are prompting some employers to skip pre-employment and random drug testing. Simo of HireRight notes that some Silicon Valley companies typically don’t screen for drugs because they know they would lose a large number of qualified applicants if they did. “But deciding whether to test is a delicate balance, especially in safety-conscious industries,” he says.

In Colorado, which legalized recreational marijuana in 2012, some employers have begun to relax their drug testing policies. About 3 percent of employers surveyed recently by the Mountain States Employers Council said they have eliminated all marijuana testing, while 7 percent stopped pre-employment testing but retain it for other situations, such as reasonable suspicion of cannabis use.

“There was a spike in drug testing across the board in 2014 after marijuana started being sold, because employers feared their workforce was going to be impaired or have diminished capacity because of reefer madness,” says Curtis Graves, information resource manager at the Mountain States Employers Council. “Two years later, however, that wasn’t borne out.”

With lower unemployment rates in the U.S. now, “some employers have to put up with marijuana use away from the workplace or risk not filling positions,” he adds.

To avoid losing valuable talent, some human-resource consultants suggest that companies consider giving workers a second chance if they test positive for marijuana, namely that they agree to another test within the next year and they will be fired if the result is positive again.

While businesses may forgo pre-employment and random marijuana screening, many will still test people who show signs of impairment or reduced productivity. In such cases, some states require employers to provide proof of erratic behavior, such as changes in speech or problems with dexterity, as well as a downward trend in performance.

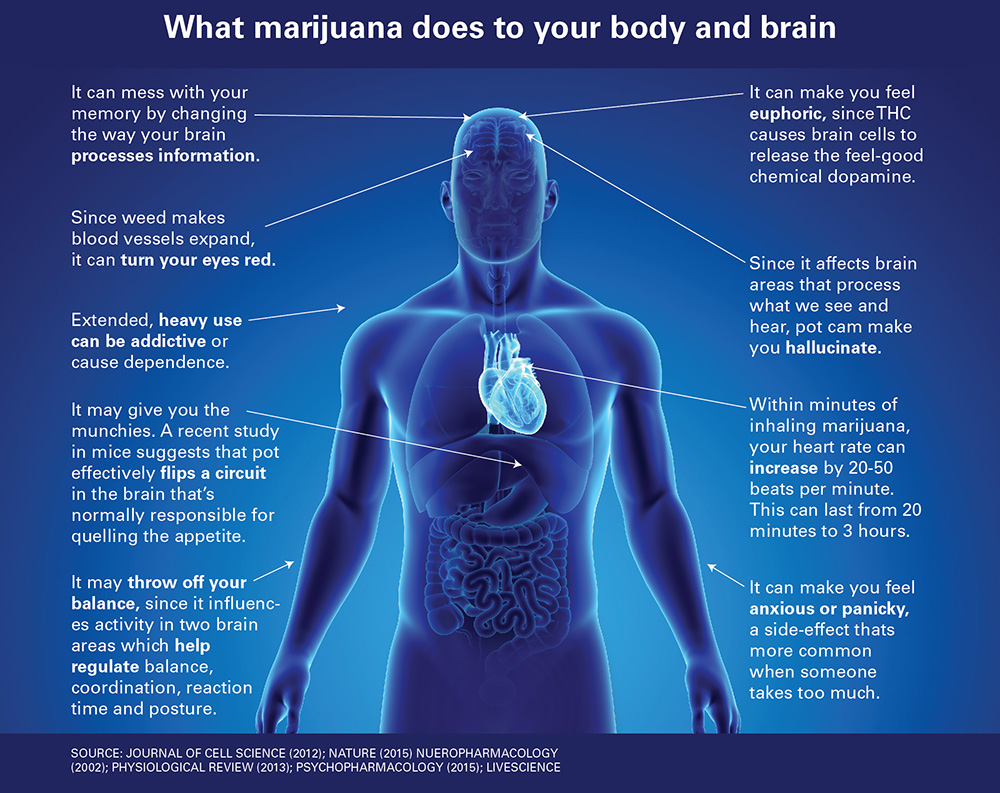

But a workplace accident or deterioration in performance could be unrelated to marijuana, despite a positive test result. Marijuana is commonly screened-for by identifying the presence of a byproduct, the inert metabolite carboxy-THC, which may be detectable for weeks or even months after a person has stopped using.

Because of the potential for error and the fact that a positive test result isn’t indicative of either impairment or recent drug ingestion, the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws finds urine, blood and oral fluid tests discriminatory and a violation of an individual’s rights. It recommends performance impairment testing rather than bodily fluid screens. For example, NORML says, an app called My Canary can detect performance changes by assessing a person’s memory, reaction time and balance.

Most employers are reluctant to publicly discuss their drug testing policies. Jeff Hanle, a spokesman for Aspen Skiing Co., did say that the company has maintained the same policy since marijuana was legalized in Colorado: random pre-employment testing and required testing after a ski crash, slips on ice and other accidents.

Nearly all new hires in the U.S. at CenturyLink, a Louisiana-based IT services firm, are subject to drug screens. In addition, the company conducts “reasonable suspicion testing of employees who appear to be impaired and random testing of those covered by U.S. Department of Transportation and Federal Aviation Administration rules,” Mark Molzen, a spokesman, says.

Multinational companies approached for comment declined interview requests. “It’s a perception thing,” Graves says. “No one wants to be perceived as soft on drugs. Companies fear that if they publicly say they have relaxed drug testing, it makes them open to legal liability when an accident happens and the employee involved tests positive for marijuana, even if it was used weeks before.”