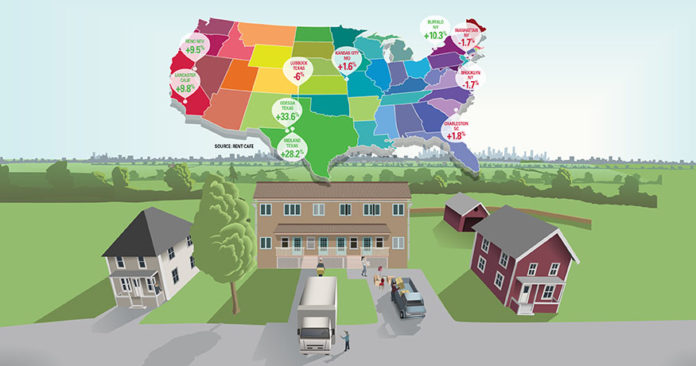

A report on the 2017 national rental market, released by RENTCafe shows that rent increases in large cities (with a population of 600,000 or more) slowed down and lagged behind the national average.

In contrast, the most dramatic price hikes hit some of the most unexpected small cities. Odessa, Texas topped the list with a 33.6 percent increase in average apartment rent, followed by Midland, Texas (28.2 percent), Buffalo, N.Y. (10.3 percent), Lancaster, Calif. (9.8 percent) and Reno, Nev. (9.5 percent).

“Odessa and Midland are special cases,” Nadia Balint at RENTCafe said. “They are highly oil-dependent cities. Their rent experienced a free fall in the previous two years due to drops in oil prices, so the price increase in 2017 is more of a recovery than growth. Average rent is now back to the 2015 level.”

Other high-growth small markets (with a population of 300,000 or less), Balint said, benefited from planned or ongoing new apartment construction. “In some of these cities, they haven’t built anything since the financial crisis,” she said.

Large cities, however, showed either decreases or much slower growth—an overdue correction, according to the report.

New York City (the research only covered Manhattan and Brooklyn), for example, saw a 1.7 percent decline in average rent in 2017. San Francisco and Boston saw weak increases around 2 percent, below inflation.

“The average rent in the U.S. has been on a relentless growth trend since 2011, reaching peak growth rates as high as 5.6 percent at the end of 2015 through mid-2016, led by the largest rental markets,” Balint said.

That said, Manhattan remains the most expensive city for renters, with an average monthly rent of $4,079. San Francisco and Boston follow at $3,430 and $3,248, respectively.

The slowdown in first-tier cities is, in part, driven by a lifestyle shift of millennials, who account for more than 60 percent of the renter population, according to Balint.

Douglas Boneparth, financial advisor and president of Bone Fide Wealth, said that millennials, especially older ones, are moving away from city centers as they have reached an age to settle down.

“For starters, home ownership is becoming more attainable and popular among this end of the demographic,” he said. “We are now a ways off the recession, plus more of us are having children, which generally changes one’s thinking about living.”

“Homeownership and the flight to the suburbs is certainly real as people start to wrestle with things like schools, daycare and transportation to work. The suburbs are simply more attractive and affordable,” he added.

Nationwide, the average monthly apartment rent was $1,359 at the end of 2017, 2.5 percent higher than 2016 and 24 percent higher than a decade ago.

In contrast, commercial real estate saw a slight one percent increase in 2017, slowing down after a 17 percent boom between 2014 and 2015.

Excerpt: Sissi Cao, Observer