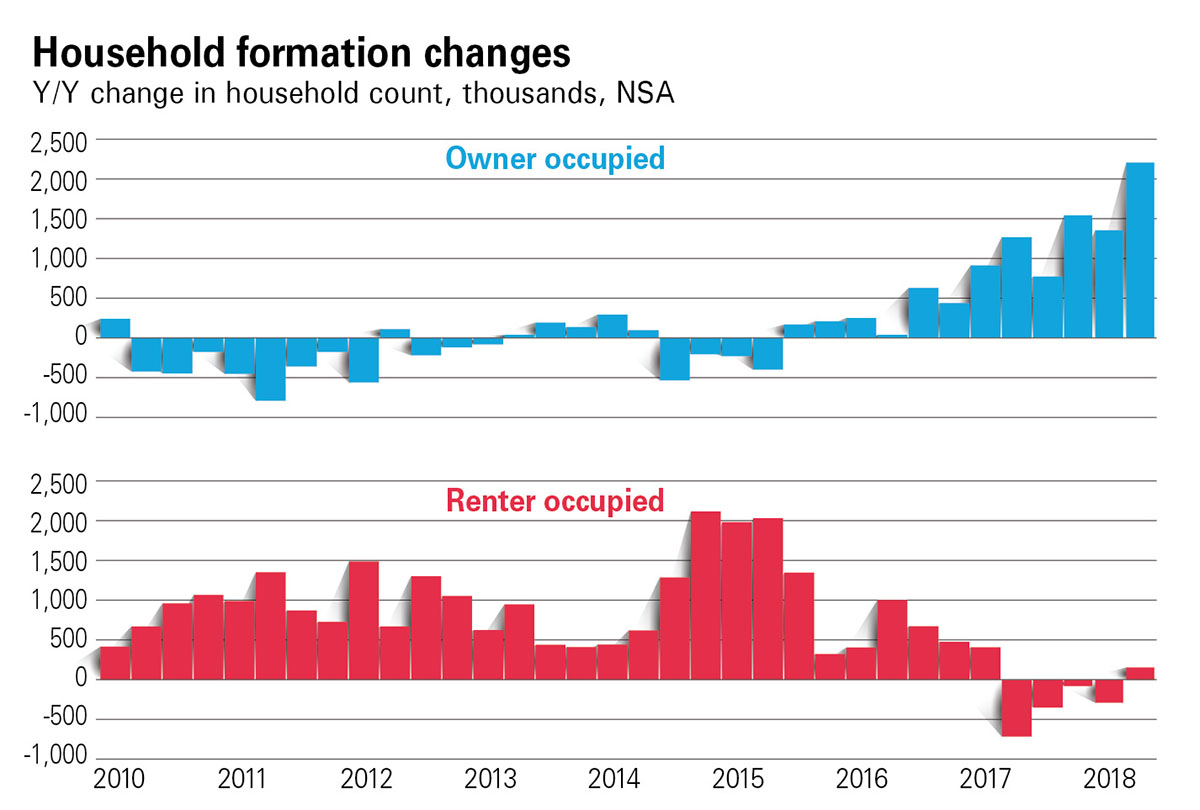

For more than a decade, those opportunities have been plentiful. There has been a heightened demand for apartments that was made larger by a significant undersupply. Will that trend continue? Here’s what we know.

Apartment demand

In 2015, the Urban Institute declared, “We are not prepared for the growth in rental demand.” The research indicated that from 2010 to 2030 for every three new homeowners, there would be five new renters. And in 2017, the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) and the National Apartment Association (NAA) weighed in: 325,000 new units, on average, are needed each year through 2030, yet an average of only 244,000 new units came online annually from 2012-2016.

Demand remains high. We’ve seen an uptick in supply, but nevertheless, there are significant headwinds hindering new supply. There are six primary reasons why supply continues to lag behind demand.

1. Loss of units

One key factor that contributes to this is the loss of units, which is estimated to be as high as 125,000 units per year. Whether it’s demolition, destruction or deterioration, every year units come off the market, impacting the supply. Unfortunately, many of those units are in the workforce housing and affordable sectors, which are already undersupplied.

2. Interest rate increases

Like it or not, we are in a rising interest rate environment. In 2018 alone, the Fed is forecasting four interest rate hikes, which would exceed what they did in 2017. As interest rates rise, it becomes more expensive to borrow money. That expense negatively impacts builders who rely on debt to finance their projects.

3. Concentration of new supply

In Fannie Mae’s March 2017 report, researchers found that almost 25 percent of new construction is concentrated in just five markets (Los Angeles, New York, Boston, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.). That trend is expected to continue for the time being. Whether or not those markets can absorb that much new supply and continue with above average rent growth is yet to be seen. It’s entirely possible that those markets may see moderation and level off from previous highs.

4. Increased cost

Land costs, labor costs and overall construction costs are increasing rapidly. Year after year increases in construction costs are having a constraining effect on the building of new apartments. The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University also looked at multifamily construction costs and came to the same conclusion that construction costs are far outpacing inflation. In the five years between 2012 and 2017 when the general inflation rate was 7 percent, vacant commercial land prices rose 62 percent, while construction costs jumped 25 percent.

To make matters worse, the recent discussion of tariffs on steel, aluminum, copper and lumber are further increasing the cost of construction. Whether this represents a short-term price spike or a long-term trend is yet to be seen. Either way, it contributes to rising overall construction costs.

5. Regulation

Creating rules that require and enforce a minimum standard of safety and quality is imperative in the construction industry. So, a certain degree of regulation is necessary. The burden from state, federal and local regulation has become particularly onerous.

Recently the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) teamed up with NMHC in a joint research effort to quantify the burden to multifamily development created by regulation. They found that on average, the regulation imposed by all levels of government accounts for a whopping 32.1 percent of multifamily development costs. Even worse, in a quarter of cases, that number reaches as high as 42.6 percent.

6. Concentration of new supply on high-end luxury properties

Inevitably the high cost of labor, land, materials and regulation makes it difficult to build anything other than on the high end of the spectrum. Unfortunately, lower-end product just doesn’t pencil out. For that reason, more and more luxury A+ product with their top-end rents are being built while mid- and lower-end product is running in shorter supply. With the escalating prices of multifamily construction, we shouldn’t anticipate those costs moderating any time soon. For this reason and more, many people are predicting that new construction will slow.

So what does this all mean?

Real estate markets are cyclical. The last several years have been phenomenal, but we’re starting to see a shift. Gone are the days in which investors could belly up for a smorgasbord of highly profitable deals. While good projects are still available, it’s important to be discriminating. New supply of luxury apartments in a handful of markets is rising rapidly. And, in a few more popular markets they are starting to overbuild. Perhaps the factors listed above will slow the pace of construction, but we’ve not yet hit a tipping point.

By focusing on well-located, stable assets built between 1985 and 2005—typically B-grade/workforce housing type locations— you minimize your risk. You’re not competing with the overbuilding and overheating around the brand new A-grade products in the marketplace. These luxury-grade assets may look pretty in the sales materials, but do they satisfy the 4.6 million of new demand needed by 2030? With U.S. median household incomes hovering around $59,000, the bulk of that need is squarely within workforce housing and not luxury units.

Excerpt: Chad Doty is CEO and Managing Partner of 37th Parallel Properties in Virginia.