In order to compete for the credits, it is essential to find a piece of land that scores the maximum number of points under the state’s complex selection system. “In Arizona, only ten to 15 deals get allocated credits each year,” Limb says. “Many developers are vying for those spots.”

According to Limb, one of Arizona’s current criteria is that the project be accessible to public transit. But many such projects have been approved in the past, and the state wants to avoid concentrations of affordable housing. That means Limb has to find possible locations with no more than one other existing affordable-housing project nearby, but which still meet other criteria, such as proximity to schools, grocery stores, and hospitals. “That’s very difficult,” he says.

In the past, Limb might have had little choice but to call real estate brokers in Arizona and ask them to wander around scouting for property that might be suitable, and then do the additional homework needed to find a good fit. But this year, he decided instead to give “big data” a try. Limb hired Visible City, a three-year-old St. Paul–based firm whose stock-in-trade is gathering and sifting through enormous amounts of information—everything from local real estate records and traffic density studies to social media posts—to help clients find whatever type of site they need.

“We can cast the net more widely for Jong than he’d be able to do otherwise,” explains Jon Commers, managing principal for Visible City. “We’re looking at every single parcel in that region, not just sites that are currently for sale. That’s millions of parcels.”

In addition to identifying sites that would meet the state’s criteria, Visible City’s analytic software can even winnow down those choices. It can filter for other characteristics—such as the age and type of existing structure, and what uses are nearby—to eliminate pieces of land that would be too expensive to purchase or not suitable for residential development.

It took several months to amass the necessary data and fine-tune the application to the nuances of Arizona’s rules. But eventually, Visible City was able to ferret out about ten suitable sites so that the developer could approach the owners and see who was willing to make a deal. “We don’t have to do the needle-in-the-haystack approach anymore,” Limb says. “We can focus on the properties that we know are quality ones, and it saves us a lot of time.”

Real estate edges into tech

Limb and Visible City are part of a trend that could transform real estate. Across the economy, industries ranging from health care to retail are amassing vast amounts of real-time information from a variety of sources in the cloud and continuously analyzing it to discern patterns, make predictions of future trends, and inform strategy. But big data has been slower to transform real estate businesspeople, with their traditional reliance on gut instinct and experience. In addition, the industry’s longstanding reluctance to invest in information technology too often resulted in data being tucked away in file cabinets or allowed to languish on the hard drives of old office computers.

But industry experts say that is changing as developers, property managers, investors, and lenders turn to both established providers of real estate data and an expanding number of tech startups to help them gather and make sense of big data and use it to their competitive advantage.

Some are using analytic platforms to study their own mountains of operational data, tracking repairs and renovations in real time so they can predict and optimize future outlays. Others are using analytics to spot financial risks and predict how a property’s performance might be affected by seemingly un-related events. Still others are using new tools that enable them to visualize the effects of changes in zoning regulations.

“Every industry ends up being similar in that it needs to embrace technological change or fall by the wayside,” says Brad Greiwe, cofounder and managing partner of Fifth Wall Ventures, a Venice, Calif.–based venture capital firm that concentrates on technology for the built environment. “Real estate has just been late to the party. But you’re starting to see that shift occur.” And as the industry transforms itself, Greiwe says, “Data analytics is an important piece.”

As recently as 2016, commercial real estate ranked close to the bottom among major industries when it came to spending on data and analytics, according to a report by Altus Group, a real estate data, software, and advisory services company, and IDC, a market intelligence firm.

But that has been changing. In 2017 alone, according to Forbes, venture capital firms, major real estate development and management companies, and brokerages invested more than $5 billion in real estate property technology, or proptech, of which big data is a part.

A 2017 report by consulting and business services firm Deloitte identified the use of data and analytics as one of five key disrupters it expects to transform commercial real estate. Pulling in and combining more and more types of information—ranging from local demographic patterns to detailed information on how occupants use buildings—could change how properties are valued and marketed to tenants, as well as where and what developers decide to build, Deloitte concluded.

Big data already is having a major impact in areas such as leasing, with the emergence of tools that enable owners to sift through their own data for insights and make quicker, smarter deals with tenants.

“It’s amazing how much the industry has evolved in the last three years,” says Brandon Weber, cofounder and chief product officer of VTS. The eight-year-old New York City–based firm is adding 200 million sq. ft. of commercial real estate space each month to its big-data platform, which enables landlords and brokers to amass their leasing, asset, and tenant information in real time, allowing them to track everything from leads on prospective tenants to how new deals might affect existing lease obligations.

With VTS giving clients a better handle on their data, they are seeing a 25 percent drop in the time it takes to do deals. “That’s found money,” Weber says. “That’s fewer days that inventory is sitting on the market and more days it is paying.”

Another rising big data firm is CompStak, a seven-year-old New York City–based outfit that deals in real estate information provided by its crowdsourcing network of more than 16,000 brokers, appraisers, and researchers in various U.S. cities, as well as some in Great Britain. Participants share their own data in exchange for credits that give them access to what others have shared.

CompStak, in turn, generates revenue by selling access to the data to institutional investors such as private equity and pension funds. Cofounder and chief executive officer Michael Mandel, a former commercial real estate broker, says the platform already contains more than 1.5 million lease comps.

But that’s not all. Mandel says CompStak has developed an algorithm, or set of guidelines, that determines precisely what the rent should be for any particular space, taking into account not just square footage and location, but also the floor on which the space is located, the age of the building, the date of the most recent renovation, proximity to public transit, and numerous other factors, adjusted for the particular market.

“In New York, it will heavily weight the number of floors a building has,” he says. “But in a market where buildings aren’t as tall, the algorithm will see that and adjust the weighting.”

Mandel says such analysis does not replace instincts and knowledge so much as augment it. “When people price rent in a building, they may have a high level of conviction about what the rent should be. But they may not have such strong feelings about what the same floor plate should be worth on the tenth floor versus the 15th.”

Meanwhile, Washington, D.C.–based CoStar Group—which helped revolutionize the marketplace in the late 1980s by marshaling an army of researchers to make calls and canvass properties to gather information that owners and brokers once kept to themselves—is leveraging big data in more ways as well.

The company’s acquisition in recent years of business-to-consumer marketing websites such as Apartments.com has provided it with a valuable new source of information and insights, and it now provides owner/advertisers with an analytics package. “We know what buildings you’re actually competing with because we can see what other buildings the consumers are looking at,” says Hans Nordby, CoStar managing director for portfolio strategy.

Nordby says the availability of sophisticated analytics tools empowers owners, who now can analyze hundreds of properties in their portfolio from their desks. “Five years ago, none of this was available,” he says.

Big data also holds the promise of reducing financial risk in real estate. CrediFi, a four-year-old firm located in New York City and Tel Aviv, has compiled information on the financing of 6 million pieces of commercial property across the United States so that users can view an owner’s entire portfolio and discern who is providing the debt, among other information. “When you don’t have data, you don’t have visibility,” says founder and chief executive officer Ely Razin. “You don’t know who to do a deal with.”

The platform enables users to see how big events affect risk. When a large company such as ToysRUs files for bankruptcy, CrediFi can tell users what properties will be affected, who owns them, and what bonds will be affected, Razin says.

Mining operational data for insights

Increasingly, property owners and managers also are using analytics to sift through vast amounts of data about their own operations. San Francisco–based software firm HappyCo offers a platform that enables companies to track and analyze routine inspections of their properties.

“Previously, everything was on pieces of paper, locked in filing cabinets—thousands of inspections across a portfolio,” says cofounder and chief executive officer Jindou Lee, a former video game designer who was inspired to develop the platform because of his own frustrations as a rental property owner. “Now, the data can be captured on a mobile device and stored in the cloud. An asset owner or property manager can have real-time visibility into the condition of the assets.”

HappyCo’s platform enables users to see patterns that might not otherwise be evident. “You can say, ‘Show me the condition of all the countertops in this property, and whether the material is marble or wooden, how many need to be replaced or upgraded, and when I need to do it,’” Lee says. “The granular level allows our customers to budget for capital projects.”

At present, owners can only study their own data, but Lee says the amount of data being amassed—such as the 31 million photos his customers took last year—is reaching the point at which he can envision eventually providing industrywide benchmarks for property upkeep.

On a more massive scale, owners and managers also stand to benefit from the mountains of data generated by sensors in smart buildings and infrastructure, which can track everything from energy consumption and environmental quality to how people use interior and exterior spaces.

Constantine Kontokosta, an assistant professor of urban informatics at New York University’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, has been involved in gathering and analyzing data from New York City’s Hudson Yards project and several city neighborhoods. In addition to data from sensors, the project is collecting a wide variety of other information—“everything from 911 call records to citizen complaints, to the amount of waste any given sanitation truck is picking up on any given day,” he says. Researchers even are gathering tweets from those areas and analyzing them to gauge things such as how pedestrians respond to Hudson Yards.

Eventually, Kontokosta says, such big data analysis could help inform developers’ decisions. “It will allow us to measure and value things that we haven’t been able to do in the past,” he says. It may be possible, for example, to see how environmental factors such as air pollution affect apartment renters’ decisions about where to live. “By building a comprehensive model of how a city functions, we can anticipate where real estate demand will occur in the future,” he says.

Turning data into maps

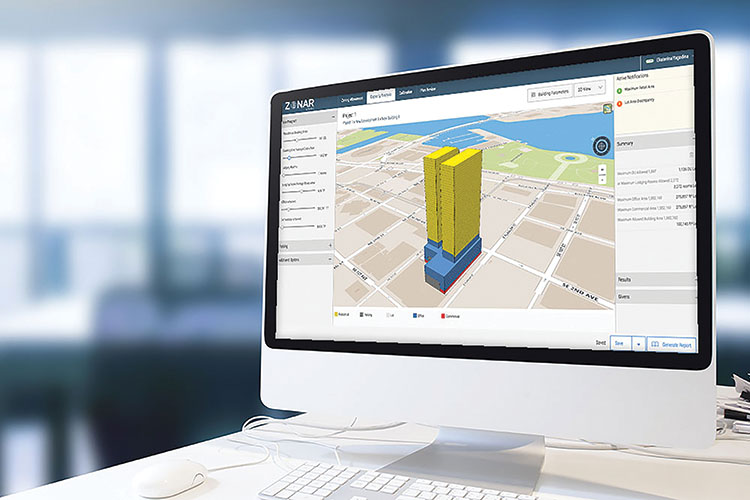

Gridics, a three-year-old Miami-based software company, has developed a three-dimensional platform called Zonar to help city governments and developers deal with the daunting length and complexity of zoning codes, and to understand site-specific development implications of the rules. As cofounder and chief executive officer Jason Doyle explains, once a city’s code is put into the software’s rules engine and applied to individual parcels of various shapes and sizes, Zonar is able to create maps and 3-D visualizations that show how zoning regulations affect land across the city. For planning department staffers, it is possible to see instantly the effects of changes to the rules.

“For example, they can analyze an entire corridor or multiple city blocks to see what a change in height or setback might mean visually, as well as how it related to density, and ultimately the effect on tax revenues,” Doyle says. After starting with Miami last year, Gridics has formed partnerships with Fort Lauderdale and other cities, and also offers private subscriptions to developers. The company announced in June that it would offer Zonar on a private-subscription basis in New York City, and plans to expand to other major U.S. cities as well.

Zonar also enables a developer to see how a project being considered would be affected by zoning limitations—or whether a different strategy might work better. “Traditionally, they would have to spend $5,000 to $15,000 to hire architects and attorneys to do a feasibility study just to understand if they actually can build what they want to build,” Doyle says. “If it’s not feasible, they still have to pay that money, and it typically takes a few weeks.”

With Zonar, in contrast, developers can do a site-specific analysis in minutes, or test drive an assemblage of parcels. They also can experiment with different uses.

“That’s where zoning gets complex,” Doyle says. “What if I build a hotel here? The parking requirements are different from a residential complex or an office building. Our system enables developers to customize and see if it works, before spending the money to proceed with the development. They can do a lot of what-if scenarios on a site for pennies on the dollar.”

The platform also can be used in reverse, to identify sites that meet certain requirements. Gridics used Amazon’s request for proposals for its next headquarters campus, for example, to identify 150 available parcels in Miami, then winnowed those down to six ideal sites near public transit, each of which would allow the e-commerce giant to develop a combination of high-rise office and mixed-use buildings that would be within zoning regulations.

Baltimore-based Datastory Consulting works with developers and other clients to turn large amounts of data into multiple maps that help reveal hidden patterns and possibilities. With the visualization, they can see that “that piece of property wanted to be this thing all along,” Datastory president Matt Felton says.

The David Hicks Company, a land brokerage and development consulting firm in Allen, Texas, has used Datastory’s platform to work with landowners who are trying to develop former farmland, such as 75 acres envisioned as a master-planned mixed-use retail/office/hotel project. “You can see who is there and what it’s going to look like in the future—the deep demographic makeup,” says the firm’s president, David Hicks. “When you’re seeing it on a map, you can visualize it more clearly.”

Big data for real estate is still in its formative stages, experts say. “We’re on the cusp of seeing much larger data sets emerge,” says Sam Chandan, an associate dean and professor at New York University’s Schack Institute of Real Estate. One of the industry’s challenges, he says, is “training a generation of analysts who really know how to work with the data and use it to make better decisions.”

But the change is likely to come quickly. “In ten years, there isn’t going to be a discernible difference between a real estate company and a technology company,” Greiwe says.

CompStak’s Mandel predicts that big data eventually will provide so much transparency to the market that it will be possible to trade buildings as if they were stocks.

“When I first said this idea six years ago, everyone told me, ‘You’re crazy. You have to walk the building because there are so many nuances.’ And I’d say that buildings are more homogenous than companies. You don’t have to walk the company when you invest in it. But now, the response I get is, ‘Yeah, I can totally see that happening.’”

Excerpt: Patrick J. Kiger