President Trump heralded the latest clarification of the tax law on a recent trip to Ohio saying that the tax had been lowered “all the way down to a very big, fat, beautiful number of zero.”

In its original form the program hit somewhat of a stall as concerns arose over how the tax rules would be interpreted. Investors participated in the rules that were clear, avoiding those areas that were not.

“This is going to make a huge difference in getting capital off the sidelines,” said John Lettieri, president of the Economic Innovation Group, the programs’ developer and promoter.

Highlights of the new rules:

Businesses qualify if 50 percent of their employees’ hours or wages are in the zone. Property and managers need to show that 50 percent of its revenue in the zone.

- Location of customers is irrelevant

- If an Opportunity Zone investment is sold and another bought with the proceeds, a period of 12-months is allowed to reinvest the proceeds, promoting multi-asset funds.

- Funds now have more time to hold investors’ money before requiring 90 percent of the investments to be in the zone

The Treasury Department is taking public comments on how to track the program’s efficiency.

“We’re going to push hard for a thoughtful framework and it’s to everyone’s benefit,” Lettieri said.

Local officials, real-estate developers, and investment managers are enthusiastic about the program. Detractors say it’s not guaranteed to help those within the zones.

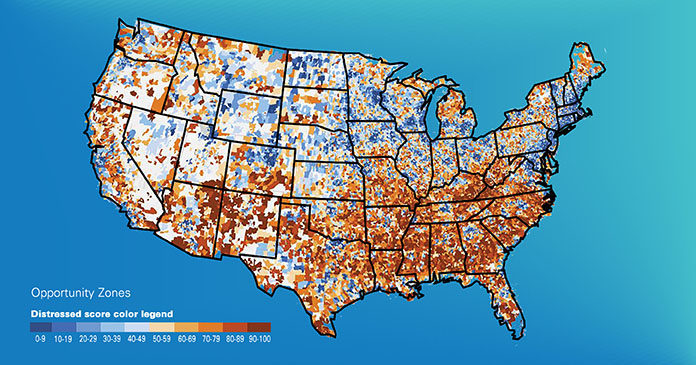

Governors were allowed to choose up to a quarter of their states’ low-income census tracts as Opportunity Zones

The program focuses on capital gains taxes paid on profits made selling investments like real estate or stocks, which are normally taxed at 20 percent plus a 3.8 percent surtax. Investors who roll their capital gains into an Opportunity Fund invested in the designated zones will be able to defer and reduce tax payments and avoid some taxes altogether.

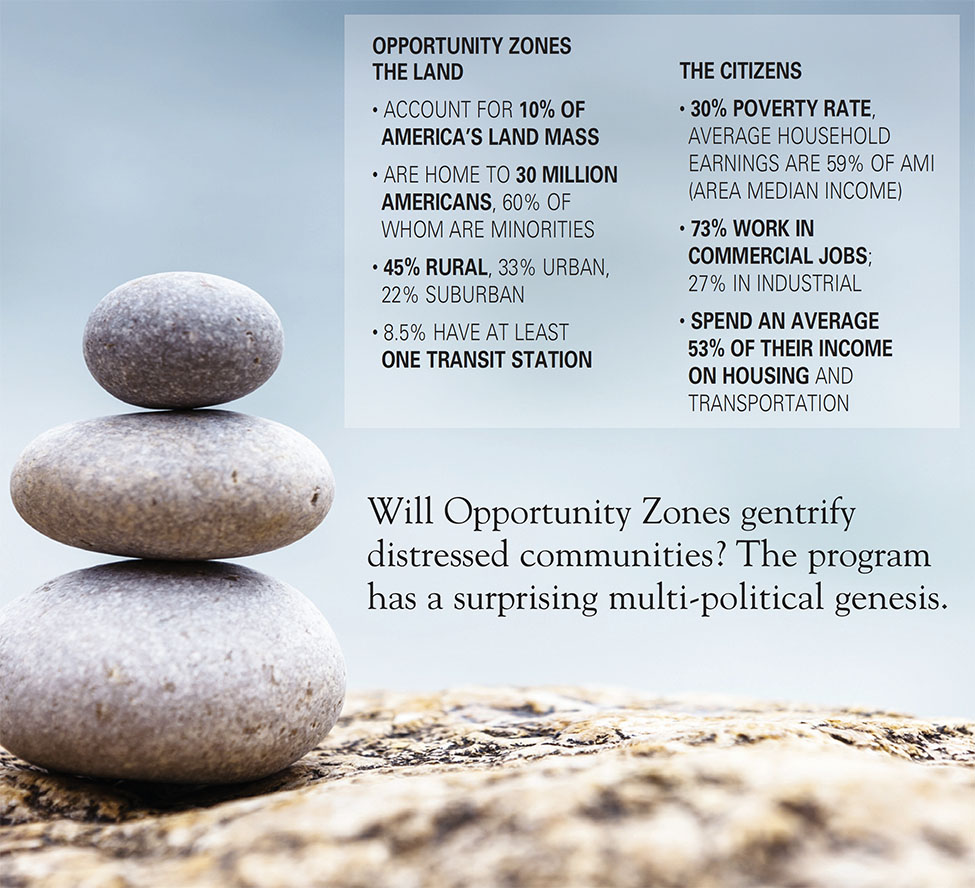

Proponents say the program will free up some of the estimated $6 trillion in unrealized capital gains in stocks and mutual funds alone held by individuals and businesses while bringing needed investment to communities in need. The so-called “O-Funds” can invest in a wide variety of assets, from stocks of new companies to real estate.

An unexpected alliance

The Opportunity Zone program was first championed as standalone legislation by a bipartisan group of federal lawmakers led by U.S. Sen. Tim Scott, a South Carolina Republican, and was rolled into the 2017 tax bill passed by Congress and signed by President Trump. It’s part of what Scott calls his “Opportunity Agenda” offering conservative solutions to socioeconomic problems like poverty and unemployment

But the program wasn’t Scott’s idea: It’s the brainchild of the Economic Innovation Group (EIG), a think tank and advocacy group launched in 2013 whose founder and chair is Sean Parker, the founding president of Facebook and co-founder of the defunct Napster file-sharing service. EIG’s founders also include Silicon Valley investor Ron Conway, Quicken Loans founder Dan Gilbert, and Ted Ullyot, who served as Facebook’s first general counsel and worked in the George W. Bush White House and as chief of staff for former U.S. Attorney General Alberto Gonzales.

EIG developed the Opportunity Zone concept in 2015, releasing a paper co-authored by researchers with the liberal Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and the conservative American Enterprise Institute. Noting that large-scale public investment is unlikely for political and fiscal reasons, the paper called for incentives to open the door to private-sector investment in communities it designates as “distressed.”

Between 2015 and 2017, EIG spent over $2.8 million on lobbying at the federal level, with much of that focused on promoting Opportunity Zone legislation, according to the Center for Responsive Politics’ OpenSecrets.org database.

“In spite of years of national growth, tens of millions of Americans live in communities that have seen no meaningful recovery from the Great Recession,” EIG said in a statement following the U.S. Senate’s approval of the program. “Tax reform is a uniquely important opportunity to ensure the tax code facilitates broader access to capital for entrepreneurs and businesses in struggling areas.”

But depending on how the funds operate, the program could end up serving as a tax subsidy for gentrification—the largely urban phenomenon in which affluent people move into predominantly poor communities, causing jumps in housing prices that can displace longtime residents. Adam Looney of the Brookings Institution points out that the Opportunity Zone subsidy is based solely on capital appreciation, not employment or local services, and includes no provisions to help current residents stay or to promote inclusive housing.

“Supporters say this will help revitalize distressed communities,” he wrote in his recent analysis of the program, “but there is a risk that instead of helping residents of poor neighborhoods, the tax break will end up displacing them or simply provide benefits to developers investing in already-gentrifying areas.”

That could have a significant impact on the South, which is home to more than half of the Americans living in distressed communities and where some cities are already struggling with gentrification. For example, a 2015 Governing magazine analysis of the 50 largest U.S. cities found that of the 10 with the highest gentrification rates between 2009 and 2013, three were in the South: Atlanta; Virginia Beach, Virginia; and Austin, Texas. Other Southern cities with at least 20 percent of eligible census tracts gentrifying over that period were Fort Worth, Texas, and Nashville, Tennessee.

In addition, not all of the money from the Opportunity Fund has to flow to low-income areas: The program has a special rule allowing governors to substitute up to 5 percent non-low-income census tracts in their nominations as long as those tracts are adjacent to nominated low-income tracts and median family income doesn’t exceed 125 percent of the adjacent qualifying tract’s. The rule was created to help governors assemble economically meaningful zones from individual census tracts.

Given how the program is structured, it will fall to governors working in concert with local officials to guide investments wisely.

“In an optimistic scenario, the tax benefits might encourage purchasing and rehabilitating residential property or expanding local businesses,” Brookings’ Looney observed. “But the value of the tax subsidy is ultimately dependent on rising property values, rising rents, and higher business profitability.”

Excerpt: Sue Sturgis, facingsouth.org