Desperate landlords now offer as much as three months free rent to potential renters at new, Manhattan apartment towers.

“There is a considerable amount of pain—20 to 25 percent declines in effective rents,” according to Ryan Davis, chief operating officer for Witten Advisors, an apartment research firm based in Dallas.

But in suburban Westchester County, just outside of New York City, a new property might offer just one month. “There is a stark difference,” he says.

In some of the hottest, most expensive cities in the U.S., new towers are trying to rent apartments. But many of the renters they hope to attract have left town. Some are moving to rent bigger spaces in suburban areas or smaller cities. Others fled severe outbreaks of the coronavirus. Others have lost jobs and are moving home to live with parents.

“The pandemic is pushing people out of the urban cores of the five or six top urban centers,” says John Sebree, senior vice president and national director of Marcus & Millichap’s Multi Housing Division, working in the firm’s Chicago office.

As a result, apartment rents are falling in some of the most expensive urban core submarkets of the most expensive cities in U.S. Rents also dropped in suburban areas, but not nearly as much. The relative strength of suburban areas has caused some speculation that the balance of power has shifted away downtown apartments back to suburban areas.

“In urban cores in the next year, vacancies will be increasing and there will be lower rents,” says Sebree. “It’s not a long term—it’s just the pendulum going back.”

Suburbs outperform downtowns

New apartments in core, urban areas in the nation’s largest cities offered deep concessions in October 2020. In addition to New York, that also includes the core areas of San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Boston and Seattle—once the hottest apartment submarkets in the U.S.

“More expensive submarkets have greater rent losses,” says Jeanette Rice, Americas head of multifamily research for CBRE.

The percentage of occupied apartments is also falling quickly in these core urban markets—more quickly than in suburban areas. “Downtown Chicago is showing softness—suburban Chicago is doing fine,” said Sebree.

For example, the percentage of apartments occupied in the urban core of San Francisco has dropped by 6.5 percentage points since the start of the pandemic, compared to roughly 2 percentage points in suburban areas. Occupancy rates have also fallen more than 3 percent in the urban core submarkets of Boston and Seattle compared to roughly 2 percentage points in suburban areas of Boston and by less than 1 percentage point in suburban Seattle. Occupancy rates have dropped close to 2 percent in Chicago, Los Angeles and New York and by less than 1 percent in the suburban areas of these cities, according to RealPage, Inc., based in Richardson, Texas.

New construction weighs on the neighborhoods downtown

Competition has chipped away at the percentage of apartments that are occupied in urban core submarkets.

The occupancy rates in urban core areas fell behind occupancy rates in suburban areas in 2015. That’s about the time when developers increased the number of apartments they built in both urban and suburban areas to roughly 300,000 units a year from 200,000 a year, according to RealPage.

Throughout this time, developers built roughly a third of their new apartments in core urban submarkets and two-thirds in suburban submarkets. “That proportion did not change,” says Greg Willett, chief economist for RealPage.

In urban cores, new apartment buildings are squeezed into small geographic areas— often filling parking lots and vacant land around downtown office towers. New towers often open on the same block as other new luxury apartment towers at similar price points, competing for the same renters.

“In the urban settings, that yields a huge increase in the number of new units that are really tightly clustered,” says Willett.

Most economists narrowly define “urban core” submarkets as zip codes in a city’s central business district or right next to it. In New York City that includes Manhattan, but not Brooklyn, Queens or the Bronx, according to RealPage. In Chicago that includes the downtown Loop and River North, but not the hipster paradise of Wicker Park. It might seem strange to count places like San Francisco’s Castro neighborhood as “suburban,” but this “suburban” designation includes many places within the borders of big cities that might have been called “trolley suburbs” in the early 1900s.

Until very recently, downtowns had a relatively small inventory of existing apartments. In many “urban core” submarkets, developers increased the inventory of apartments by 4 percent to 5 percent a year, compared to 2 percent a year in many suburban submarkets, according to RealPage.

Largely as a result of this new construction, urban core submarkets began to show lower occupancy rates than suburban submarkets, starting in 2015, says Willett.

“Many of the metro cores will take time to work off the oversupply of stock which has accumulated over the last three years,” says Doug Ressler, manager of business intelligence for Yardi Matrix, based in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Fewer young renters for new apartments

New apartment projects are also suffering because fewer young people are getting jobs and forming new households. Instead, millions of young people have lost jobs in the pandemic.

“The decline in occupancy rates is more about job losses than anything else,” says Willett.

In recent years, developers have built new apartments explicitly designed to attract young people drawn to hip, urban neighborhoods. Instead, many have moved home to live with their parents or doubled up with friends.

“We have a recession—people moving back with parents makes total sense,” says Paula Cino, vice president of construction, development and land use policy for the National Multifamily Housing Council, based in Washington, D.C.

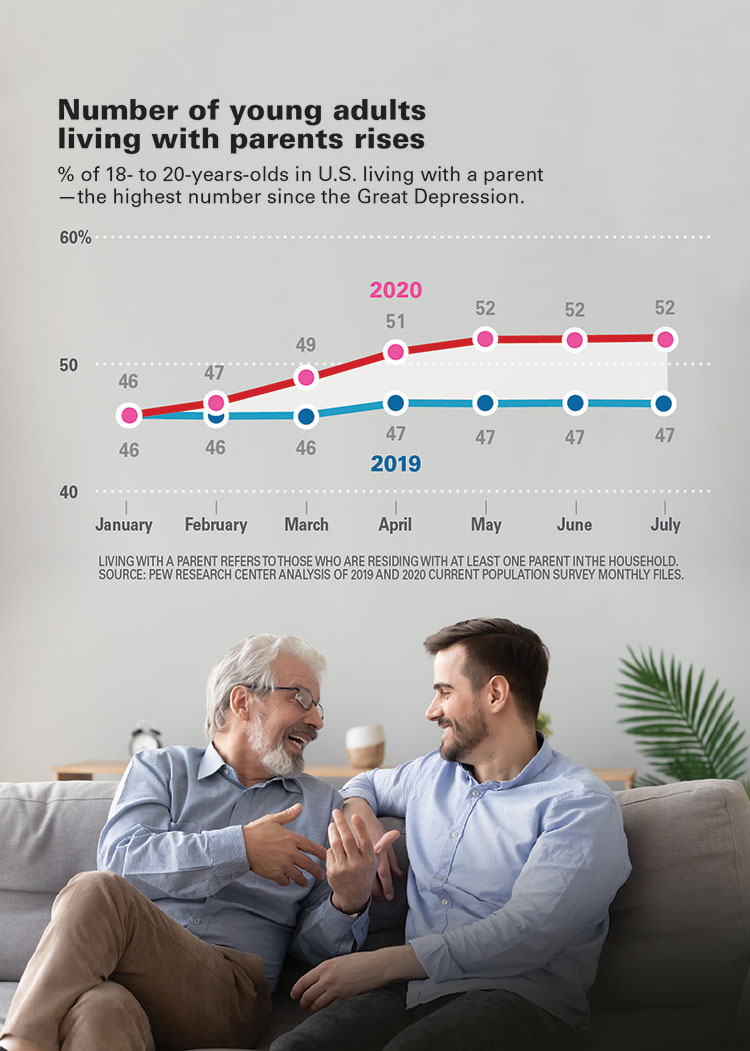

In July 2020, more than half (52 percent) of all adults under the age of 30 lived with one or both of their parents. That’s the largest percentage of young adults living with parents since the end of the Great Depression, when Census officials first started counting them, according to the Pew Research Center’s analysis of monthly Census data.

Even before the pandemic, research shows the most recent college graduates were resistant to spending money, according to Willett. That may be because many are burdened with college loans and grew up in the shadow of the Global Financial Crisis.

The number of people under 30 who live with parents has been growing for years— even when the U.S. economy was strong. In February 2020, after more than 10 years of consistent economic growth, almost half (47 percent) of young adults lived with parents, according to Pew.

Renters flee expensive downtowns

Apartment properties in the most expensive urban core submarkets are also losing some renters to suburban areas or even the downtowns of other, less expensive cities.

“Owners are getting a lot of people from New York City moving into New Jersey and Philadelphia and Connecticut,” says Sebree.

Apartment rents in core urban submarkets of the top 50 metro areas average $1,955 a month, compared to $1,349 in suburban areas. Rents are even higher in top downtowns.

“The biggest issue is affordability,” says Walter Hughes, chief innovation officer and vice president for Humphreys & Partners Architects headquartered in Dallas.

Apartment rents are typically lower in suburban areas compared to more densely-developed downtowns—simply because apartments cost less to build. “In the suburbs, land is less costly. You can build a four-story, surface-parked, wood-frame building, which is much less expensive than high-rise construction,” says Hughes. “That is part of the reason people are moving to the suburbs.”

Some of the renters moving may be Millennials who have finally married and now need more space for their growing family than an apartment in the urban core can provide. Two-thirds of the influential Millennial generation are now in their 30s. Even before the pandemic, a growing number of them had moved out of urban apartments to rent or own larger spaces, according to NMHC’s Cino.

“The movement out to the suburbs was not caused by COVID-19,” says Sebree.

Other Millennial households had kept living in urban neighborhoods, resisting the call of the suburbs much longer than earlier generations of city dwellers. “There was pent up demand,” says Sebree. “Then in the pandemic, so much of the reason that you live in the city was temporary taken away. As leases have come up for renewal there was the opportunity to move.”

The ability to work remotely has also freed workers to live in less expensive places where they can afford more space and perhaps a better quality of life. “For a lot of people, that is a bit liberating. They can move out and still perform their job like they used to in the concrete jungle,” says Hughes.

During the first months of the pandemic, many workers discovered that they could do their jobs from any location with a good internet connection. “You cannot underestimate the ability to work remotely,” says Sebree. “Five years ago, we didn’t have cloud computing. It is now much easier to work from a remote location and because of the pandemic, we were all forced to become experts at it.”

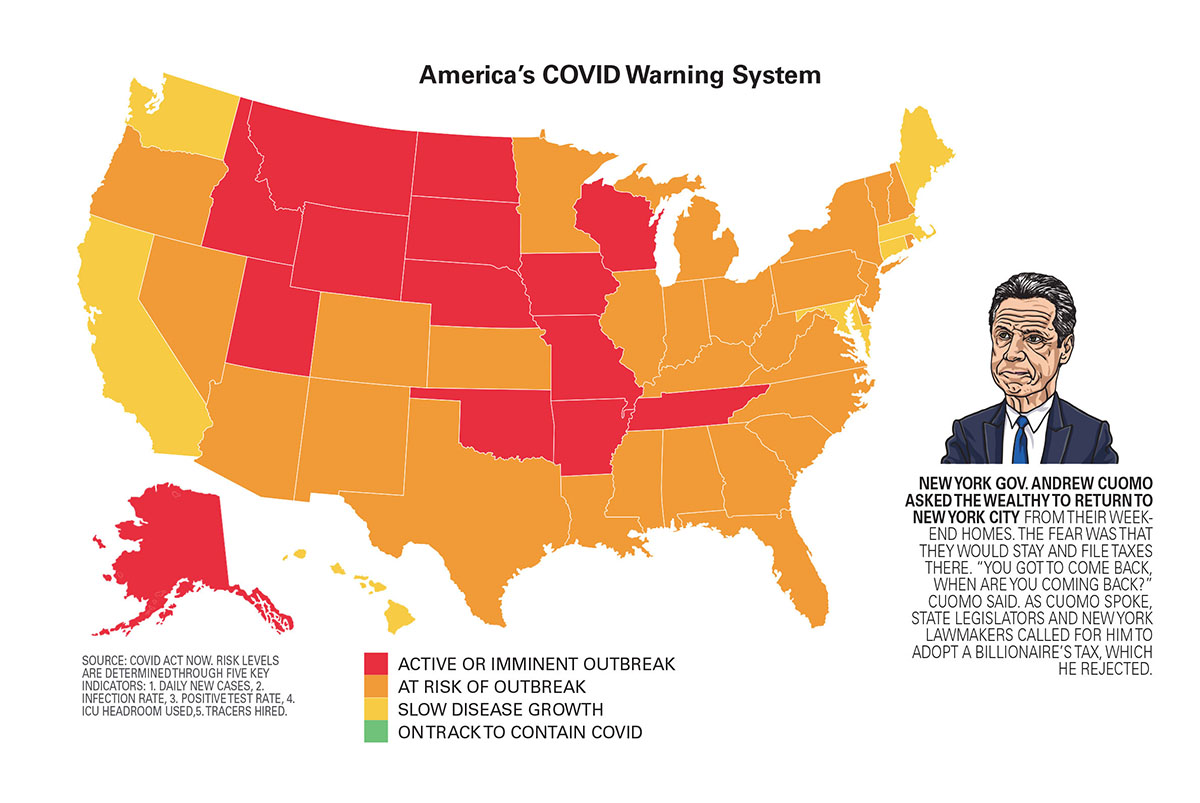

Other problems that drove people away from cities like New York and San Francisco might not prove to be as lasting as the challenge of affordability. Crowded, urban New York City was once site of the worst coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. Many wealthy New Yorkers left the city to live in second homes like beach houses in the Hamptons or condominiums in Miami. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo famously asked some of these coronavirus refugees to return.

However, in late September and early October, New York City had fewer new cases than many rural states—less than five per day per 100,000 people, compared to more than 50 in North Dakota. The latest hot spots for the coronavirus also include rural Wisconsin, Utah and Montana.

It turns out that living in an apartment tower doesn’t create significantly more risk of catching the coronavirus than living in a neighborhood of single-family houses, according medical research analyzed by NMHC. “It’s not really the number of people who live in a building, it’s the number of people in a unit,” says Cino.

Pundits and presidential candidates have also said that crime rates in big cities have risen during the pandemic. For example, the number of shootings in New York City doubled or even tripled during some weeks this summer compared to the year before. But the number of shootings—or crimes of any type in New York—is still low so far in 2020 even compared to ten years ago when then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg made a habit of bragging about how safe the city had become.

Downtowns perform well in less expensive, smaller cities

In smaller cities, apartments in downtown, urban cores are also benefiting from some people who are moving out of larger, more expensive cities.

“There are a few cities that are dealing with a percentage of renters who are choosing to leave,” says Sebree. “Outside of those big cities that are reliant on public transportation, the other cities are doing pretty well. Cities like Austin and Nashville are doing extremely well right now.”

In smaller cities, downtown apartment submarkets have not been damaged nearly as badly in the crisis as in the six biggest cities. Occupancy rates often sagged by a just a percentage point, according to RealPage. “While new demand has stalled to some degree, there’s not net resident loss in the urban cores across places like Dallas, Atlanta and Charlotte,” says Willett.

Some developers are still interested in building new apartment towers in these very urban environments.

In the last few months—despite the recession caused by the coronavirus—developers have asked the architects at Humphreys to start work on density studies and site plans for three new proposals to build apartment towers in urban neighborhoods of smaller cities.

“We started on new plans for high-rise, apartment developments in Nashville, Tenn., Naples, Fla., and Austin, Texas,” says Hughes.

In total, half of the new projects that Humphreys has started is working on since the pandemic began are mid-rise or high-rise buildings. “In prior years we had high-rise apartment projects in Manhattan, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Those have projects have disappeared.”

Developers are also asking the architects at Humphreys to draw up preliminary plans for new apartment developments in the suburbs. About a third of these proposed developments arein walk-able communities. “People are craving that—a compact core with restaurants and a coffee shop,” says Hughes. The length and depth of this trend remains to be seen.”

Author Bendix Anderson