Developers aren’t waiting for a vaccine for the novel coronavirus. They have been busy planning projects to build new apartments, even as doctors diagnose new infections in the U.S. at a rate of more than a hundred thousand per day.

The economic chaos caused by the coronavirus is far from over. But by the end of 2020, developers are likely to have started construction on the majority of apartment projects planned before the global pandemic. Developers are also planning for a future after the pandemic.

“Sales of development sites have held up through the downturn,” says Jim Costello, senior vice president for Real Capital Analytics (RCA), a research firm based in New York City. “These developers saw that this is a temporary dislocation—They have a pretty reasonable expectation that we will be back to normal by the time that building is finished.”

Developers buy new land to build new apartments

In the second and third quarters of 2020, while much of the U.S. still worked from home to slow the spread of the virus, developers spent $16.7 billion to buy land for new developments in the U.S., according to RCA.

“The second quarter trends were down… but the third quarter really came back,” says RCA’s Costello.

That’s only 4 percent less than developers spent over the same period in 2019, before the coronavirus. RCA’s numbers don’t specify what types of properties these developers are planning, but new apartment buildings probably account for many, since many office and hotel developers have reportedly slowed or stopped planning new buildings.

Architects who specialize in new apartment buildings are also very busy—considering that the U.S. is in the grip of a deadly pandemic.

“Business is almost back to normal—it is very strong going into 2021,” says Walter Hughes, chief innovation officer and vice president for Humphreys and Partners Architects, based in Irving, Texas. In a typical year, Humphreys conducts about 800 “feasibility studies” that show how many apartments could potentially fit on a proposed development site. Business for the firm had nearly returned to that rate as 2020 came to a close.

Construction starts will not be down by much in 2020

Developers are also busy building the apartments they had planned before the coronavirus struck. They had lost several months during the first wave of the pandemic, when health officials and state governors ordered most non-essential business to close to slow the spread of the disease.

But they have rapidly made up for lost time.

By the end of the year, developers are expected to have started construction on 292,000 new apartments in 2020 in the largest 150 metropolitan areas in the U.S., according to RealPage, Inc., based in Richardson, Texas. That’s only slightly below the rate of new construction over the past few years, which hovered at a little more than 300,000 units a year.

Developers had already started planning most of these projects long before the doctors diagnosed the first coronavirus infections. It’s not surprising that many developers found a way to break ground as soon as they could gather a construction crew.

“Substantial capital had already been spent on those projects,” says Greg Willett, chief economist for RealPage. That often includes millions of dollars to buy development sites, draw up plans, arrange financing and win zoning approval to build.

“This year has taught us what we are capable of doing remotely and in many ways hastened an evolution that was already underway,” says Josh Wooldridge, vice president of development for the NRP Group, based in Gaithersburg, Md.

“Everyone has had to get creative.”

Developers build a little less in the most expensive cities

Development slowed down dramatically in some the most expensive apartment markets in the U.S. for most of 2020—though more developers began construction even in these places as the year came to a close.

“Through the first three quarters of the year, multifamily starts were down by 50 percent in Seattle and New York, and 75 percent in San Francisco,” says Andrew Rybczynski, managing consultant for CoStar Advisory Services, based in Boston, Mass. Property managers in each of these markets struggled to rent new apartments, especially in luxury towers that opened downtown during the pandemic. Many offered as much as three months of free rent to lure new residents. “San Francisco is a particular outlier on rent losses through the past eight months,” says Rybczynski.

However, developers returned to action in the last months of 2020. In the New York City metro area, developers are on track to have started construction on 36,000 new apartments by the end 2020, according to Witten Advisors, based in Dallas. That’s less than the 44,000 new apartment developers started in 2019—though it’s significantly more than the 30,000 new apartments that developers started to build in 2018.

“You would think a market like New York City would be down dramatically but it’s not,” says Ryan Davis, chief operating officer for Witten Advisors.

Developers are expected to keep trying to build in New York City. “We expect that there are folks out there trying to get their hands on sites and land,” says Davis. These sites might now be available for less. “Apartment developers would not have to compete with office or hotel developers—So even with lower apartment rents those deals might still make sense.”

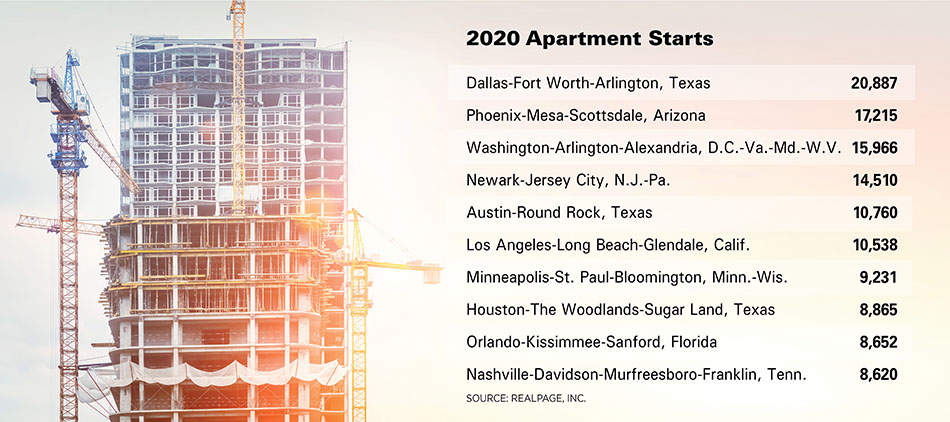

Despite all this activity, New York City is unlikely to be one of the top markets for apartment starts in 2020, according to RealPage. “The other notable market missing from [RealPage’s] list is Seattle, where development is pulling back from previously very aggressive levels,” says Willett.

Instead, developers seem to be giving more attention to relatively inexpensive metro areas—where they can build apartments that more people can afford to live in.

“Start volumes are way up in a few markets, especially Phoenix and Northern New Jersey,” says Willett. “Most of the Northern New Jersey activity is in Jersey City and Hoboken, providing housing options that are more affordable than in Manhattan.”

Developers are also building more new apartments in a handful of growing metro areas like Phoenix, Raleigh, San Antonio, Nashville and Palm Beach. They started construction on more new apartments in these metro areas in the first three quarters of 2020 than any time since 2014, according to CoStar.

Once again, developers had planned many of the properties that they started to build in 2020 long before the pandemic struck. These new construction projects may show that developers were less focused on the most expensive markets like New York City and Seattle. However, these construction projects do not show that developers were tired of urban downtowns in general—at least not before the pandemic.

Of the apartments that developers started to build in the first nine months of 2020, 20 percent are rising in downtown areas—compared to 19 percent in 2019, 19 percent in 2018, and 20 percent in 2017, according to CoStar. “The figure is the same share of a smaller number,” says Rybczynski. “Although there hasn’t been an overall shift away from downtowns, there has been a shift away from the Tier 1 metros that tend to have more high-rises.”

Developers have looked to the suburbs for years

For several years, developers have been eager to build more apartments in less expensive, suburban areas. “Those suburban properties were outperforming the urban core locations,” says Davis. Rent growth has been higher, on average, in suburban areas than in many, more expensive, downtown areas. That partly because in many urban downtowns, developers built new, high-rise, luxury apartments slightly faster than the market could absorb.

“Everybody saw that and was interested in moving out [to develop apartments in suburban areas],” says Davis. “The movement to the suburbs has been around for three or four years now.”

But the goal has proven to be difficult to achieve.

Despite their interest in the suburbs, developers have not managed to start construction on significantly more suburban projects over the past few years.

“There has not been a material pickup in construction starts in the suburbs,” says Davis. That’s because apartments are very difficult to develop in the suburbs. “Once you get out into the suburbs, it is very difficult to get a deal built.”

Since the pandemic, developers rush to build suburban apartments

The urge has only gotten stronger since the pandemic to build new apartments in relatively inexpensive, suburban areas instead in expensive downtowns.

“Everyone is looking at the suburbs right now,” says Hughes. At Humphreys and Partners, roughly 80 percent of the feasibility studies they have done in the second half of 2020 are for proposals to build new apartment buildings in suburban areas. Of these, about half are for low-rise, wood-frame buildings. That’s up from 50 percent in recent years.

“In the suburbs, rent is cheap and the density of housing is low,” says Hughes. “You don’t have to build a concrete garage.”

Apartment developers are attempting to follow a set of renters who have moved out of expensive urban areas in search of more space and cheaper living—especially since the pandemic. “There was an increase in demand for larger suburban units,” says NRP’s Wooldridge. “Many renters are in need of extra space for homeschool, exercise and offices.”

Of these renters, many are still likely to want to live within walking distance of amenities like shopping or a coffee shop—even if they now live in the suburbs. “A property’s Walk Score still matters,” says Davis. That will especially be true if these suburban renters are working from home.

“The most desirable sites are within walking distance of an “urban” place where you can get a cup of coffee—a little downtown—with a neighborhood a quarter mile around it,” says Hughes.

However, not all feasibility studies turn into actual construction projects. Some of these idyllic sites may prove to be too far from employment centers, even with the advent of telecommuting.

In many parts of the U.S., suburbs have proven to be places where land to build on is hard to find and approval to build is difficult to get—especially at the parking ratios that local officials require. Many zoning boards hesitate to even consider new multifamily developments for families that could bring more children to their school districts and traffic to their streets.

“In the Mid-Atlantic, the suburbs have become more difficult to develop than urban areas,” says NRP’s Wooldridge. “It’s not as easy for developers to just pivot as one might think.”

Also, demand for city living from renters has not vanished, according to RealPage’s Willett. He is one of the researchers who have most carefully noted demand for apartments weakening in urban areas across the U.S. more quickly than in suburban areas. But occupancy rates even in these weakened, urban markets still average above 90 percent, he says.

“While 2020 urban core apartment demand proved weaker than it was previously all across the country, some product absorption continued in most cities,” says Willett. “Manhattan, downtown San Francisco and select neighborhoods in Los Angeles are really the only spots that registered sizable drops in the number of apartment renter households.”

Even these more expensive markets may be more affordable to some renters who continue to keep their jobs through the pandemic until a working vaccine for the coronavirus is widely distributed sometime in 2021. “Savings rates are rising, consumers are flush with cash they haven’t been able to spend,” says Davis. “Absolutely there is going to be pent up demand in the gateway cities like San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York City and Seattle.”

“While some are theorizing that construction will cool in the urban core and rise in the suburbs, the actual start figures so far don’t really back up that story,” says Willett. “That could change as we get into 2021, but don’t count on it, especially if the rollout of COVID vaccines proves successful.”

Author Bendix Anderson