Long before coronavirus and lockdowns, millions of U.S. households suffered from a shortage of housing that pushed rents higher and outpaced wage growth.

Now the U.S. is beginning to recover from the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns that destroyed businesses across the country and brought financial harm to hundreds of thousands of lives.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) continues to help millions of renters who lost income during the crisis catch up on unpaid rent.

HUD officials may have hundreds of billions more to distribute if Congress passes the $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan, created by President Biden’s White House. The plan also includes provisions that address housing supply and quality.

Even if the American Jobs Plan dies in a divided Congress, HUD has plans to address some of the fundamental problems that created the housing shortage—and possibly create opportunities for apartment builders and developers.

Housing crisis grows

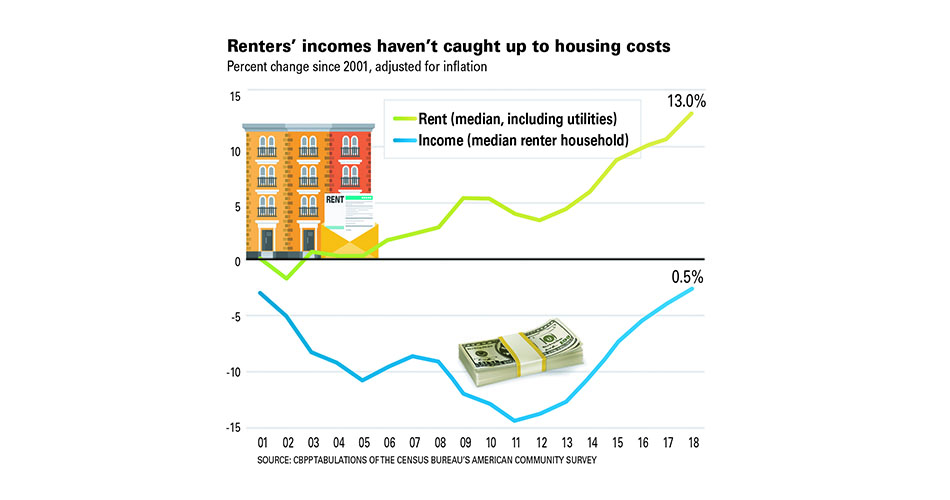

The U.S. faces a housing shortage that has been growing for years. Since 2000, rents rose by 13 percent while incomes remained stagnant.

“The challenges to HUD’s constituents have never been higher,” said David Dworkin, president and CEO of the National Housing Conference (NHC), based in Washington, D.C.

Even before the pandemic, incomes had not kept pace with rents or household expenses. Some analysts estimate that as many as 11 million people paid more than 50 percent of their income on rent.

“Millions of people were on the brink of housing instability, eviction, and possible homelessness because their budgets were stretched so thin, said Peggy Bailey, senior advisor to the Secretary on Rental Assistance for HUD.

The need for affordable housing is much larger than the assistance now provided by government programs. Less than a quarter of the households eligible to receive federal rental assistance can actually receive a Sec. 8 housing voucher.

“Many cities have shut down their waiting lists,” said Kimble Ratliff, vice president of government affairs for the National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC), based in Washington, D.C.

The housing shortage has been made worse by housing policies that make it more difficult to create new homes, according to HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge.

For decades, zoning laws—like minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking requirements, and prohibitions on multifamily housing—have been at odds with inflated housing and construction costs and locked families out of areas with more opportunities, Fudge said.

“Discriminatory zoning is a violation of the law. We are going to find resources and build new housing. You cannot build it if people are saying ‘not in my backyard,’” said Fudge.

While zoning in and of itself is not discriminatory, the restrictions it places on developers may drive up the cost of housing. However, many see the problem as more complicated than zoning or building costs.

Compliance with federal, state and local regulations add, on average, 32 percent to the cost of a multifamily construction. Regulations may add as much as 43 percent to the cost for over 25 percent of all new multifamily builds. This is according to a ground-breaking study by the National Association of Home Builders in 2018.

President Trump created his own White House Council on Eliminating Barriers to Affordable Housing Development in June 2019. The Council targeted federal, state and local regulations that added to the cost of developing affordable housing.

Stimulus creates opportunity

“This is a pivotal and transformational moment in both HUD’s history and our nation’s housing policy,” said Bailey.

In March, the Biden White House released its $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan. That plan includes $213 billion that will pay to build and modernize more than 2 million affordable homes. It represents a “once-in-a-century opportunity to invest in our affordable housing supply,” according to HUD.

A lot of this money is expected to finance development and rehab work through expansions of existing programs like federal low-income housing tax credits and funds for public housing.

The plan also promises to “eliminate exclusionary zoning and harmful land use policies,” according to the White House.

Building and renovating a few million houses and apartments is a big goal. Convincing communities around the U.S. to change their zoning laws is much more ambitious.

“There is incredible potential to change overall housing affordability in the U.S.,” said Bailey.

The White House has provided a few hints how it might “eliminate exclusionary zoning,” which are mostly set by local governments.

The White House plan calls on Congress to “enact an innovative, new competitive grant program that awards flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to eliminate such needless barriers to producing affordable housing.”

Housing advocates like Dworkin believe that small towns and suburbs that have historically resisted new housing development will not suddenly change their zoning laws—at least without more substantial inducement.

Pressure on local communities

“The Fair Housing Act should be a powerful tool to remedy these inequalities,” said Bailey.

The 1968 Fair Housing Act protects people from discrimination when they are renting or buying a home according to six protected classes: race or color, religion, sex, national origin, familial status and disability. Neither fiscal inequality nor social engineering are part of the law.

Under President Obama, HUD’s Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) regulation was created. The regulation sought to eliminate racial disparities in housing even if those disparities were caused by economic factors and not by overt racial discrimination. The regulation was ended under President Trump last year. Biden has reinstated the rule, promising enhancements.

States, cities and counties that receive money from programs like Community Development Block Grants (CDBC) use the money for a variety of purposes, including economic development. To continue receiving this money under AFFH, local jurisdictions must prove that they “affirmatively further fair housing.”

This means that officials must gather and analyze data on barriers to housing choice, integration and fair housing. They must then create a plan to address those barriers and comply with AFFH through designated outcomes, regardless of intent.

Assessments are submitted as part of a community’s regular, five-year spending plan for HUD programs.

Opponents contend that the AFFH rule has little basis in the Fair Housing Act, that the requirements for funding are burdensome and that compelling equality of outcomes over simple nondiscrimination implies control that recipients don’t possess.

Even so, over 900 of the 1,200 jurisdictions who had participated in AFFH sued HUD last year to reinstate the program.

“Communities that receive federal funds must take affirmative steps to make their housing fairer and remedy longstanding segregation,” said Bailey. “As Secretary Fudge has said, she believes in this requirement, and will ensure that it is followed.”

Cities and counties will likely be on the hook again for the next cycle of program funding—and they will probably have to submit something similar to the reporting and planning required by AHHF.

“Fair housing is the law of the land,” says Fudge. “The prior administration did roll back some fair housing tools that we have. We’re looking at how we can go back and make those better and get them re-implemented, if possible.”

Leveraging transportation money

Even CDBG money from HUD programs might not be enough to motivate some localities to allow additional housing construction.

However, many jurisdictions rely on funding from the federal Department of Transportation (DOT) to pay for the roads that link residents to job centers.

Some housing advocates wonder if the Biden White House might revive another initiative from the Obama Administration: a federal interagency partnership between HUD, DOT and Environmental Protection Agency called the Partnership for Sustainable Communities.

The Partnership had proposed to link some kinds of transportation funding to the Partnership’s sustainable development goals like “promoting equitable, affordable housing.”

No renewal of the Partnership has been announced yet. Housing providers are keeping a close eye on signs that HUD might work more closely with DOT and the agency’s new Secretary, Pete Buttigieg, a former mayor.

“Mayor Pete is very familiar with affordable housing challenges,” says NMHC’s Ratliff. “Watch whether Mayor Pete and the HUD Secretary are doing joint events and policy discussions.”

American Jobs Plan, public housing

HUD could also receive significant money to improve programs like public housing.

The new infrastructure plan includes $40 billion to repair public housing properties that have been underfunded for decades, according to HUD’s estimates.

By 2020, the list of repairs needed at public housing properties across the U.S.—including basic needs like replacing worn-out roofs, boilers and elevators—added up $70 billion, according to the National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials, based in Washington, D.C.

Fudge views the money in the Jobs plan as a down payment. “I’d like to see a stream of resources available to do this—not just in this package, but ongoing,” says Fudge. “We cannot, through this package alone, repair and restore 50-year-old housing authorities across this country which are crumbling every day.”

HUD also plans to improve the ways its programs help developers build affordable housing. Currently, HUD plays a supporting role in financing many of roughly 100,000 units of affordable housing that are rehabilitated or built from scratch every year. Most of the financing for these projects comes from the federal low-income housing tax credit program, which is run by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and administered by state and local housing officials.

HUD programs like Home Funds and CDBGs provide extra capital.

“These programs were not created to intentionally work together,” says Bailey. “The American Jobs Program gives us the opportunity to think about how to help these programs work together better.”

The Biden Administration has also announced its intention to fully fund the Sec. 8 rental assistance program, so that every household that qualifies for a voucher can get one.

The expansion would unleash a powerful funding tool for the development of affordable housing. An affordable housing developer can use dependable money from a project-based Sec. 8 contract to support a substantial loan from a bank.

More money for Sec. 8 rental assistance could also fuel an expansion of HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration Program, which helps recapitalize crumbling public housing properties, by replacing undependable capital funding from Congress with more dependable Sec. 8 contracts that can support bank loans.

It’s not clear how much of this money will actually be included in a budget that is passed into law by a sharply divided Congress.

Parts of the Biden Administration’s infrastructure proposal are likely to become law, according to housing advocates—like certain tax credits that have bi-partisan support. “The broader outlook is much more complicated,” says Dworkin.

HUD distributes coronavirus funding

All this is in addition to HUD’s immediate task in helping the U.S. Treasury distribute emergency funding to help renters recover from the economic chaos resulting from the coronavirus pandemic.

In March, Congress passed the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan Act, in addition to an earlier $900 billion coronavirus relief bill, signed in December by President Trump.

To help renters who lost income during the pandemic, the two laws include a total of roughly $50 billion in rental assistance that will be distributed mostly from the Treasury to state and local housing officials.

This is thought to be enough to makes up for the estimated amount of missed rental payments.

HUD will distribute nearly $11 billion to people living in Indian country, and provide people experiencing homelessness with emergency housing vouchers, services and property acquisition resources in places that need more affordable housing.

HUD staffs up

In the years after the Great Recession, Congress relentlessly cut the budgets of agencies like HUD. Between 2009 and 2018, the number of staff working at HUD fell by 19 percent.

Certain offices at HUD were under particular pressure. At the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, the number of employees fell by nearly 30 percent.

“We are thousands of people short of where we ought to be,” says HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge. “They are under-resourced, understaffed, and overworked.”

The agency is moving quickly to fill its empty desks—hiring staff almost twice as fast as it did in 2020.

Author Bendix Anderson