Can society be designed? Can an expert engineer alleviate people’s pains and struggles with a good-enough central plan and blueprint?

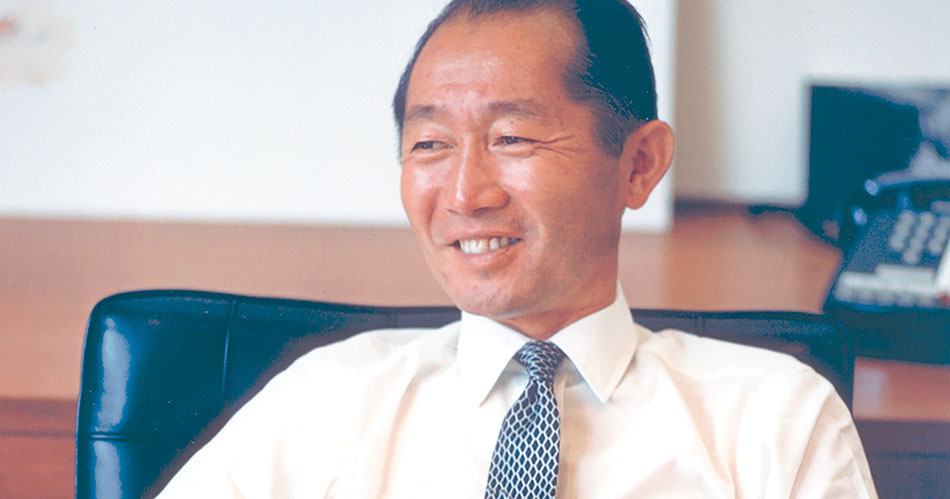

Minoru Yamasaki thought so.

Yamasaki was one of America’s most well-respected architects in the 20th century and was a member of the school of thought that people’s human nature could be improved (whether those people needed or wanted improving) by a properly planned building surrounding them.

Yamasaki got to test his theory by designing the public housing complex that promised to be a template for all public housing going forward. The complex, St. Louis’ Pruitt-Igoe, was made possible by post-war New Deal housing and urban development programs. And like many New Deal initiatives, Pruitt-Igoe was guided by the idea that good intentions, centralized planning, and strong government power would progress society more than protecting people’s rights or personal choices.

Pruitt-Igoe, and Yamasaki’s designs, were sold as the solution to poverty, crime, and housing in America’s major cities, but within just a few years, the complex would show the dangerous consequences when government planners take away people’s liberties and homes.

Sheer will could change people

Yamasaki’s childhood reads like a Horatio Alger novel. His parents emigrated from Japan and settled in Seattle at the turn of the century. His father worked three jobs to provide what he could for the family, but it was a hand-to-mouth existence nonetheless.

Seattle was not a great place to be Japanese, and Yamasaki never forgot his bitter memories of being denied access to pools and harassed at theaters.

He put himself through undergrad at the University of Washington by doing grueling work at a salmon canning plant during his summers. He’d work anywhere between 70 and 120 hours a week. The pay was $800 a month in today’s dollars.

But the work paid off and Yamasaki showed true promise in architecture. He suspected the anti-Asian sentiment in Seattle would stifle opportunity, so he moved to Manhattan with all of $40 in his pocket. He enrolled in a master’s program in architecture at NYU and wrapped dishes for an importing company to pay his way.

But what a time to study architecture. This was the high modernism era: Walter Gropius, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Le Corbusier were rethinking everything. Breakthroughs in glass, steel, and concrete created new possibilities.

Le Corbusier, or Corbu as he was known, was a major influence for Yamasaki. Corbu was perhaps the most extreme of the high modernists. He had unyielding faith in the power of rationalism and efficiency to im- prove every facet of society.

He considered homes “machines for living.” The master planner could create literal utopias by exerting his expert will from the top down.

Yamasaki was eager to implement Corbu’s ideas in American cities. After Yamasaki graduated from NYU, he was officially an architect and joined the firm Shreve, Lamb & Harmon, best known for designing the Empire State Building, among many other towering buildings in Manhattan. After World War II ended, he worked at a few other firms before starting his own firm in 1949.

Yamasaki had plenty of experience. What he didn’t have was a signature building. But that would come soon enough.

High modernist architecture met a perfect ally in the postwar urban renewal movement, which shared the same “raze it all and start from scratch” ethos.

Government seizing for profit

Slum clearance and urban renewal sprung up across the U.S. after the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Berman v. Parker in 1954, a decision that was breathtaking in its surrender to government power.

A Washington, D.C., department store owner sued the D.C. Redevelopment Land Agency after the agency began proceedings to take the department store through eminent domain, demolish it, and sell the land to a private developer.

The government claimed it was solving “blight,” but the plaintiff argued the government was simply taking private property and giving it to another private party.

The Supreme Court sided with the government in a major loss for property rights. The decision effectively expanded governments’ power to invoke eminent domain from “when strictly necessary for the public good” (say, an airport) to something like “whenever politicians think it’s best,” a ripe opportunity for cronyism and corruption.

The Berman decision also came on the heels of the Housing Act of 1949, which vastly expanded the federal government’s involvement in housing. The main elements were federal financing for slum clearance and urban renewal, expanding mortgage insurance to increase home ownership, and the construction of public housing units.

Between the Berman decision, a windfall in federal money for interventionist housing policies, and an ascendant architectural movement with visions of creating utopias through buildings and design, all the ingredients for a grand-scale government failure were about to erupt.

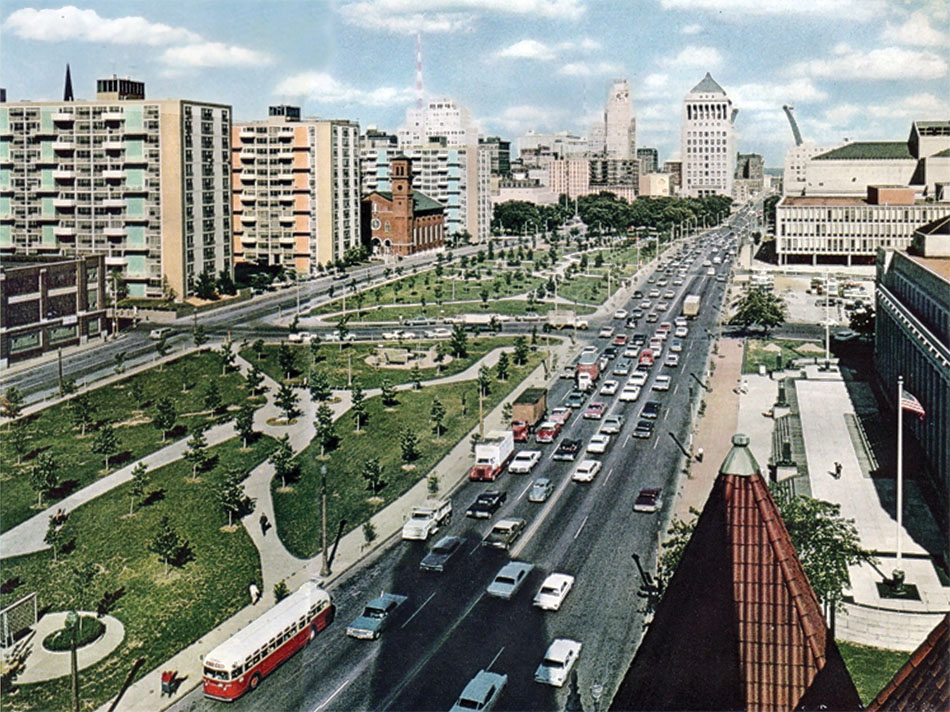

Postwar St. Louis was ready for a makeover; one historian said it resembled “something out of a Dickens novel.” The city’s population had grown significantly and local leaders assumed it would continue to grow at the same clip for decades.

They feared tenement housing would overtake the central business district. Even though local voters had rejected a proposal for high-density public housing in 1948, with federal money now so abundant, large housing projects were hard to resist.

Joseph Darst, the Democrat mayor of St. Louis, didn’t need convincing. Nor did Republican state officials. The bipartisan consensus was that radical action was needed for the city. Darst put the case bluntly: “We must rebuild, open up and clean up the hearts of our cities. The fact that slums were created with all the intrinsic evils was everybody’s fault. Now it is everybody’s responsibility to repair the damage.”

Social engineering by elite

Darst and other city officials began what author Jeff Byles calls a “multipronged assault on five square miles of the city.” Soon demolition crews were eradicating entire neighborhoods.

The neighborhood of Mill Creek Valley alone saw the demolition of some 5,000 buildings, including 43 historic churches.

While city leaders considered these neighborhoods to be irredeemable slums, not everyone agreed, and many residents had been happy to call the demolished neighborhoods their home. Former Mill Creek Valley resident Gwen Moore said, “My memories are very pleasant, and I remember being traumatized when we were told that we had to move.”

Race was a factor in city leaders’ motivations. Part of the reason St. Louis was expanding was that many black southerners were moving to the city from the South to escape Jim Crow. Meanwhile, whites were leaving the city in droves. For many black Americans, urban renewal seemed like a containment effort. Black author James Baldwin famously changed (corrected) the term to “Negro removal.”

The flagship development plan to replace the razed neighborhoods was for a high-density public housing project called Pruitt-Igoe, named after two St. Louis heroes: Wendell Pruitt, a Tuskegee Airman, and William Igoe, a former congressman.

The Pruitt buildings would be for Blacks, and Igoe for whites. But the project, which launched in 1954, had to lose this segregated design conceit after the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which ended the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Officials had a general idea of what they were looking for in the project’s design: tall, modern buildings that would both accommodate a growing metropolis and end impoverished conditions in St. Louis’ tenements. Construction was funded by state and federal money, but the complex was intended to be self-sustaining from the working-class residents’ rent.

What they didn’t have yet was an architect up for the challenge. For that, city leaders selected a promising young architect named Minoru Yamasaki.

One bad assumption after another

Yamasaki’s initial proposal was a blend of Corbu and his own ideas about how to improve people’s lives through architectural design. From Corbu, he drew heavily from the unrealized Ville Radieuse: rows of high-rises, threaded by a “green river” of foliage and playgrounds. Most important was Corbu’s economy-of-scale idea—fit as many units as possible into the buildings.

Yamasaki’s initial proposal included a mixture of two-story walk-ups, mid-rises, and widely spaced 11-story blocks. He incorporated a new type of “skip-stop” elevator. These stopped only on every third floor, which both saved room for more units and encouraged a sense of community engagement by forcing residents to interact more. Or so he hoped. The hallways were wide and “streetlike,” again to mimic a sort of town square inside the high-rises.

The design was widely praised. An Architectural Forum article titled “Slum Surgery in St. Louis” called Yamasaki’s proposal “the best high apartment of the year.” City leaders boasted about the high-rises, claiming that these slum residents would now have more magnificent views of the city than its richest residents. Tall, modern buildings that granted light and fresh air, where there were once polluted slums.

While Yamasaki’s designs were adjusted by St. Louis officials (they scrapped the smaller buildings for 33 high-rises), Pruitt-Igoe was the culmination of many turn-of-the-century progressives’ plans for government’s top-down role in every aspect of society. But like many of the New Deal plans and programs, the promises of Pruitt-Igoe were only truly viable on paper, and the utopian dreams of Pruitt-Igoe began shattering before the first high-rise was even built.

Death by elite ego

City planners thought St. Louis was undergoing a population boom. It wasn’t. Amity Shlaes, in her book Great Society, explains how local authorities were convinced “St. Louis would grow and sustain its citizens. Instead, in part because of other interventions by authorities, the city shrank. Economies, it turned out, were like humans. They made choices.”

The Housing Act’s provision of government-backed mortgage insurance meant suburban housing was cheap and getting cheaper. So were cars. President Eisenhower’s interstate highway project, which (arguably) began with the paving of I-70, connected St. Louis with the blossoming suburbs of St. Charles just across the river.

Despite the decision in Brown v. Board, white families were taking that same FHA money that funded Pruitt-Igoe and buying homes in the suburbs, and many jobs went with them.

This fundamentally changed the city. De facto segregation soared; the city shrank and suburbs swelled. If St. Louis’ leaders realized their assumption of continued economic growth and population growth was wrong, they kept it to themselves.

The beginning of the end

It quickly got worse from there. Planners expected the working poor to live in the complex. Instead, many unemployed families took the apartments, which meant—because families receiving welfare paid the lowest rents—the rent revenue wasn’t enough to sustain the building.

Also, under Missouri’s welfare laws at the time, you could receive welfare only as a single parent. This left many mothers and fathers with the grim options of staying together without the state benefits, or separating in order to receive benefits.

Many fathers left their families to search for work wherever they could find it. They often didn’t return.

Soon Pruitt-Igoe was mostly populated with large, single-parent families. The lack of fathers in the building (and social workers ran regular checks to ensure dad really wasn’t living there) had dangerous ripple effects for Pruitt-Igoe children.

Crime quickly became common, and children joined gangs, vandalized and damaged the buildings. Maintenance workers had trouble keeping up and occupancy dropped rapidly.

The day President Lyndon Johnson gave his famous “Great Society” speech in 1964, residency in the complex hovered around 25 percent.

And what of Yamasaki’s innovative skip-stop elevators? His wide hallways? Did they foster a sense of community as he intended? Amity Shlaes paints a bleak picture:

[The] elevators… were muggers’ traps. Poor maintenance meant the elevators often jammed, leaving gangs’ victims in with them for long extra minutes. The gangs lurked in the halls and made tenants “run the gantlet” to get to their doors.

Young men threw bricks and rocks at windows and streetlamps; the activity was a regular sport. There were no good playgrounds. Because there were no toilets on the ground floor, children had accidents there, and the elevators gradually became public toilets. The community area was a sorry joke; its only function, ultimately, was as a place for collecting Housing Authority rents. No one seemed able to stop the decay.

St. Louis quickly realized that Pruitt-Igoe was a problem. But it was unclear who, if anyone, could fix it. The federal government, the St. Louis Housing Authority, the state, and the City of St. Louis itself all shared responsibility for the complex. When a problem belongs to everyone, it belongs to no one.

Deplorable mistakes

Within five years of its launch, Yamasaki was regularly apologizing for his role in the project. Though the final design of the complex differed from his original vision, he came to question the core assumption behind the project: that people’s lives could be effectively engineered through urban design.

He expressed regret for his “deplorable mistakes” with Pruitt-Igoe. By the 1950s, he was giving eloquent speeches about the “tragedy of housing thousands in exactly look alike cells,” which “certainly does not foster our ideals of human dignity and individualism.”

To the Detroit Free Press, he put it more simply: “Social ills can’t be cured by nice buildings.”

By the early 1970s, the 33 concrete tombstones lining St. Louis’ skyline were a cautionary tale for utopian housing schemes. It was a den of crime and misery, rather than anything anyone could call home. When the decision came to demolish it, occupancy was only 10 percent.

The day the demolitions began at Pruitt-Igoe, architectural historian Charles Jencks declared the death of high modernist architecture and its grand assumptions: “It was finally put out of its misery. Boom, boom, boom.”

Three towers were demolished in 1972. The last tower finally came down in 1976, leaving nothing of Pruitt-Igoe behind.

Yamasaki’s fate was permanently tied to Pruitt-Igoe.

Throughout his long career, he had successfully built airports, consulates, convention centers, and college buildings. He designed the World Trade Center with its iconic Twin Towers and even graced the cover of TIME magazine for his impact on American architecture.

But Pruitt-Igoe had damaged his reputation, and it took a toll on his later work. Toward the end of his career, his buildings became muted and stylistically indistinguishable. When he died in 1986, his New York Times obituary included a section on Pruitt-Igoe under the subheading: “One Big Failure.”

But Yamasaki was not wholly to blame for the failure of Pruitt-Igoe. Neither were Corbu’s ambitious ideas, flawed as they were. The Pruitt-Igoe project was doomed before Yamasaki’s proposal was even submitted.

It was doomed when St. Louis politicians uprooted thousands of St. Louisans from their homes and forced them into massive concrete towers that they hadn’t asked for. The design, which the residents had no say in, was totally alien to them.

“There was nothing soft in Pruitt-Igoe,” one former resident remembered. St. Louis’ planners and politicians thought they could treat citizens like guinea pigs in a grand social experiment.

Put bluntly, the road to hell is paved with government interventions.

The cost in lives

The tragedy of Pruitt-Igoe for Yamasaki was what it did to his legacy. While he began his career subscribing to the high modernist and progressive mentality of the possibilities of top-down control, after he saw the error of his thinking, he evangelized against it. But Pruitt-Igoe will always be the stain on his incredible portfolio of beautiful buildings.

The tragedy of Pruitt-Igoe for society is how it ruined people’s lives. Thousands of poor, blue-collar workers and transplanted southern black families became victims of Pruitt-Igoe’s failures. But despite the poverty, crime, and human destruction Pruitt-Igoe caused, not one government official was held accountable for its failings, and Yamasaki was the only one whose reputation suffered.

In the end, the lesson Yamasaki took away from Pruitt-Igoe’s failure is prescient of the eternal failure of government policies that violate individuals’ rights: “In spite of my vision for how architecture could genuinely improve the lives of people, it seems that certain real social and economic conditions make this impossible.”

Government can’t create utopias, and every time it tries, people’s rights—and many times their homes—get destroyed.

Authors Joseph Kast, Jim Burling, Pacific Legal Foundation