For months, corporate hegemons, real estate brokers and their media acolytes have been insisted that a return to “normalcy,” that is, to the office, was imminent. Some companies threatened to reduce the incomes of remote workers, and others warned darkly that those most reluctant to return to the five-day-a-week grind would find their own ambitions ground down to the dust. Workers have been reported to be “pining” to return to office routines.

Fears of returning to the office due to the Delta variant have delayed a mass return to gateway cities. Office vacancies grew in August. Since the pandemic began, tenants gave back around 200 million sq. ft., according to Marcus & Millichap data, and the current office vacancy rate stands at 16.2 percent, matching the peak of the financial crisis. Overall, it is widely expected that office rents will not recover for at least five years.

Things could get ugly as some $2 trillion in commercial real estate debt becomes due by 2025, particularly in large, transit dependent central business districts, reflecting in part reluctance among commuters to ride public conveyances. This is a world-wide phenomenon—occurring in New York, Hong Kong, Paris, London, and other financial centers—and accompanied by a marked decline in business travel, with conventions and meetings particularly devastated.

A new economic geography

Where is the work getting done? Increasingly, in the suburbs and exurbs of the big metros, smaller metros, cities and even some rural areas, all of which offer lower urban densities, which usually means less overcrowding.

In the first year of the pandemic, big cities, according to the firm American Communities and based on federal data, suffered the biggest job losses, nearly 10 percent, followed by their suburbs, while rural areas suffered 6 percent and exurbs less than 5 percent. The highest unemployment rates today are in coastal blue states, while the lowest tend to be in central and southern states.

The shift toward dispersed and remote work suggests the beginnings of a new geographical and corporate paradigm. Suburbs and exurbs accounted for more than 90 percent of all new job creation in the last decade, but with the rise of remote work, proximity to the physical workplace has lost more of its advantages. University of Pennsylvania Professor Susan Wachter notes that telework eliminates the choice between long commutes and inordinate housing costs. The areas where remote work is growing most are generally small cities, as well as Sunbelt locales in Florida and South Carolina.

The dispersion of work is not a matter of low-wage workers heading to cheap places to do low-status jobs. In metros over one million such as Raleigh-Cary, Austin, Orlando, Salt Lake City, Nashville, Phoenix, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Charlotte, professional and business-services jobs are growing much faster than they are in San Francisco, Chicago, New York, or Los Angeles.

The number of employees using the office started to drop as early as 2017 in San Francisco, the biggest winner in the tech economy.

The pandemic supercharged these trends. The disturbing rate of fatalities and hospitalizations in the Northeast, notably New York City, including Manhattan but particularly the poorest sections of the outer boroughs, chased many urbanites to the suburbs, exurbs, and beyond. Even as infections spread to other regions, it remained easier to endure the pandemic in a more spacious house, particularly if mass transit is not necessary.

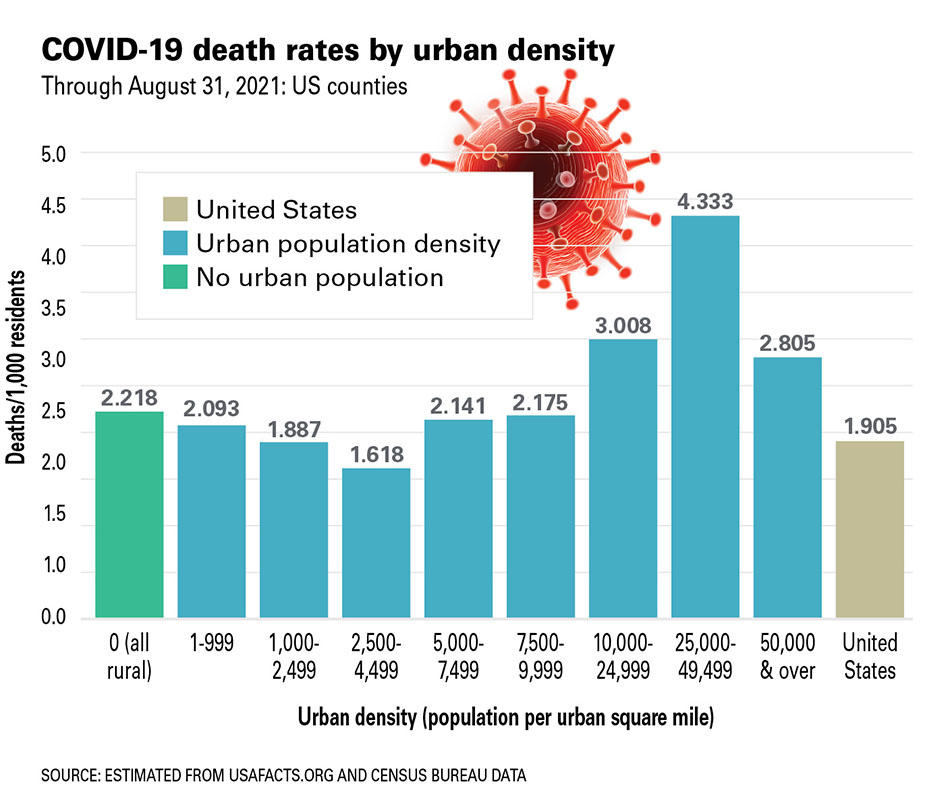

Demographer Wendell Cox shows that, despite the considerable spread to less crowded areas over the past year, areas with the highest urban densities, in spite of their lockdowns, have experienced two times or more overall adjusted Covid fatalities, after more than one year of draconian social distancing regulations that eliminated much of downtown employment and cut mass transit use by up to 90 percent.

Car-dominated places, where people can more easily afford space, have lower infection and fatality rates; if other pandemics follow, as many suspect, memories of the recent hegira will remain.

The longer the pandemic lasts and new variants appear, the greater will be what new research from Jose Maria Barrero, Nicholas Bloom, and Steven J. Davis refers to as “residual fear of proximity.”

The team suggests that when the pandemic fades, roughly 20 percent or more of all work will be done from home, almost four times the already growing rate before the pandemic. A study from the University of Chicago suggests this could grow to as much as one-third of the workforce and as high as 50 percent in Silicon Valley.

Roughly 40 percent of all California jobs, including 70 percent of higher paying work, could be done at home, according to research by the Center of Jobs and the Economy.

The fading central business district

What was most remarkable about the past year was how well the economy continued to function in a dispersed manner. Many firms—though certainly not all—found that remote work helped the bottom line.

The prospect of ditching expensive space has significant appeal. Telecommuting is transforming work at banks and leading tech firms, including Facebook, Salesforce, Microsoft, Google, LinkedIn, and Twitter, often bringing surprising productivity gains.

This shift has been particularly tough on large, transit dependent downtowns, since many businesses depend on daily invasions of armies of office workers. The largest central business districts (CBD) still resemble “ghost towns,” noted The Financial Times.

In October 2020, foot traffic in midtown Manhattan was down 57 percent, compared to an 8 percent deficit throughout the “city region.” In the city of San Francisco (including the CBD), volumes were down 54 percent compared to 17 percent throughout the region. The article showed similar results for Chicago and Boston. Similar results have held throughout the U.S.

Offices in New York, with by far the largest CBD in the nation, are now occupied at levels barely half that of cities like Houston. According to Kastle Systems, virus concerns around public transportation, skyscrapers, and also the city’s population density are at the root of the concern.

A Partnership for New York survey of its members revealed that roughly three in four of them will either allow a hybrid model or require no presence in the office at all. Google, for instance, announced initially it would return to its Manhattan offices, but workers will only be required to come in three days a week.

The company has also said up to 20 percent of its staff can apply to work remotely full time. Meanwhile, employees seeking to work remotely have accused the company of hypocrisy when a senior manager announced his impending move to New Zealand.

To be sure, millions of workers, particularly younger recruits, will eventually return in order to boost their career paths and meet potential partners. But the move will be slow, despite exuberant claims that tech workers were flocking back to San Francisco.

Rising office vacancies, three times the pre-pandemic levels, are enough to fill 17 Salesforce Towers, San Francisco’s tallest building. The Wall Street Journal detailed a national review of U.S. Postal Service (USPS) change of address requests, at the county level. Up to 10 percent of San Francisco’s households left the city during the past year, a pattern seen also in Boston, Chicago, and New York; New York City saw more net moves out last year than it did during the two prior years combined. By a New York Times estimate, the city lost 420,000 residents in the early months of the pandemic.

This is nearly as much as the entire gain from 1950 to 2019, when the population expanded by 455,000 residents.

The new class struggle

With hundreds of billions of dollars of some of the world’s priciest real estate at stake, corporate executives and office owners will resist this shift. Highrise offices, where space is a premium, are hierarchal by nature.

The most prestigious firm generally gets the nicest views on the highest levels, while the grunts stay further down. The “corner office” of the elite executive has become even more rarified as most workers have been herded into open floorplans with little privacy.

For the economic elite, life in the big city offers many enticements—cultural events, great restaurants, access to media—generally unmatched at a suburban home or office park. Big city life is good if you can afford a luxurious Manhattan apartment and an estate in northern Westchester.

When the city gets too cold, Mike Bloomberg can take his jet to Bermuda while urging the proles to cut back on energy consumption. These are not the options of the middle-aged worker bee commuting daily from Ronkonkoma.

Silicon Valley giants like Apple announced that its return to work policy would require employees to be in the office three days per week, but this was not enough for many Apple employees, who felt the policy should go further; in one recent survey, 90 percent said they wanted the option of working indefinitely at home.

This reluctance is common through the white-collar workforce. In a recent survey of over 5,000 employed adults, 40 percent expected some level of remote work flexibility post-pandemic.

Roughly 60 percent of U.S. teleworkers, according to Gallup, wish to keep doing so, at least for now. Overall, as many as 14 to 23 million remote workers may relocate as a consequence of the pandemic, according to a recent Upwork survey; half of them say they are seeking more affordable places to live.

Workers in families, particularly women, overwhelmingly favor working full or part time from home, notes one recent survey. This is especially true for millennials, once thought wedded to city life but now attracted to work at home, which addresses issues, according to a Conference Board survey, like enhanced “life-work balance.”

Working remotely also has clear environmental advantages. With a 50 percent reduction in annual delay hours, lower congestion levels reduced fuel consumption by 51 percent. Greenhouse gas emissions during peak period commutes dropped 50 percent.

In their struggle against demand for full time office occupancy, workers may be able to exercise greater leverage, due to deep-seated labor shortages, the highest quit rate in over two decades, and low labor force growth.

“You see tons of bold statements. Companies saying, ‘No remote work.’ Some companies are saying, ‘We’re getting rid of all of our offices,’” says Bret Taylor, president and chief operating officer of Salesforce, Inc. But in reality, it’s the employees calling the shots. “There’s like a free market of the future of work and employees are choosing which path that they want to go on.”

So despite the concerns of property owners and developers—some still talking about new high rise offices in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Houston—considerable dispersion and loss of office tenants will persist.

In the post pandemic future of work, nine out of 10 organizations will be combining remote and on-site working, according to a new McKinsey survey of 100 executives across industries and geographies.

According to the Wall Street Journal, technical and engineering employees applicants are insisting on being able to work from home part of the time. “It’s become really sort of a requirement if you’re looking for top talent,” according to a software executive.

New power centers

The CBD, particularly in the legacy city, reflects a hierarchy of place. In the vision of urban boosters, businesses located in the central core—Manhattan, the Loop, downtown San Francisco—would control the “commanding heights” of the economy.

Everything else was basically a backwater, where the masters of the universe placed their less well-paying and critical functions. In recent decades, a whole urban religion has grown up around the notion, tied to the migrations of elite workers from elite schools, that only a few locales can attract high-end workers in sufficient numbers.

This notion is increasingly outdated. Exciting cities like New York, San Francisco, Chicago, and Los Angeles will maintain their allure for the highly educated, particularly those without offspring, as well as for young adults whose families can help with high rents. But these “superstar cities” have surrendered a growing number of workers to less glamorous, and less dense, places. Indeed since the mid-2010s, growth in professional, technical, and scientific services—the largest high wage sector—grew faster in Raleigh-Cary, Austin, Orlando, Salt Lake City, Nashville, Phoenix ,and Dallas/Fort Worth than in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

This follows migration patterns. Virtually all the metros enjoying the fastest growth since 2015 are in the southwest, the Intermountain West, Florida and through the south. These boomtowns, as well as some Midwestern metros, now attract on a per capita basis more millennials, minorities, and the foreign born than the cool big cities on the coasts.

Even before the pandemic there were ample reasons, particularly for people over 30, to move to suburbs and exurbs—less crime, lower housing prices, better schools. Suburbs were the choice of two thirds of millennials well before the pandemic.

The new “hot” locales for skilled workers in California are increasingly found in more rural counties. Overall, in most metros, home prices have risen most further from downtown.

Perhaps most hopefully, the pandemic also will help reverse the concentration of power in a few places, and corporations. A more dispersed economy is not only better for people’s lives, but suggests a new hope for our battered democracy.

Excerpt Joel Kotkin, americanmind.com