As mortgage rates have risen this year, the buyer demand for homes has fallen. That has spelled trouble for the home construction business. Homebuilder confidence dropped for the tenth straight month in October. The decline in builder sentiment reflects what economist Ian Shepherdson describes as “housing… in free fall. So far, most of the hit is in sales volumes, but prices are now falling too, and they have a long way to go.” The University of Michigan’s index of buying conditions for homes has fallen to the lowest level since 1982.

Meanwhile, in November, mortgage demand for home purchases is “down 41 percent from a year ago and close to a seven-year low.”

Naturally, this has been a sizable drag on the sale of newly constructed homes. According to the Census Bureau, September sales of new single-family houses in the U.S. were down by 17 percent year over year. They were also down by 10.9 percent from the previous month. Overall, sales of new homes are down 42 percent from the peak in August 2020.

Nor does it look like construction of multifamily housing is likely to make up for the decline in single-family housing. Although it might stand to reason that a decline in buyer demand for housing could lead to more rental housing, that doesn’t appear to be the case. According to HousingWire, the “historic multifamily housing construction boom is already fading.” This is partly due to the fact that rising interest rates are not limited to mortgages. “Those same interest rates pushing would-be homebuyers to the sidelines are also hurting multifamily developers.”

It’s getting more expensive to borrow money up and down the housing food chain, and that’s slowing down new construction of both for-lease and for-purchase housing.

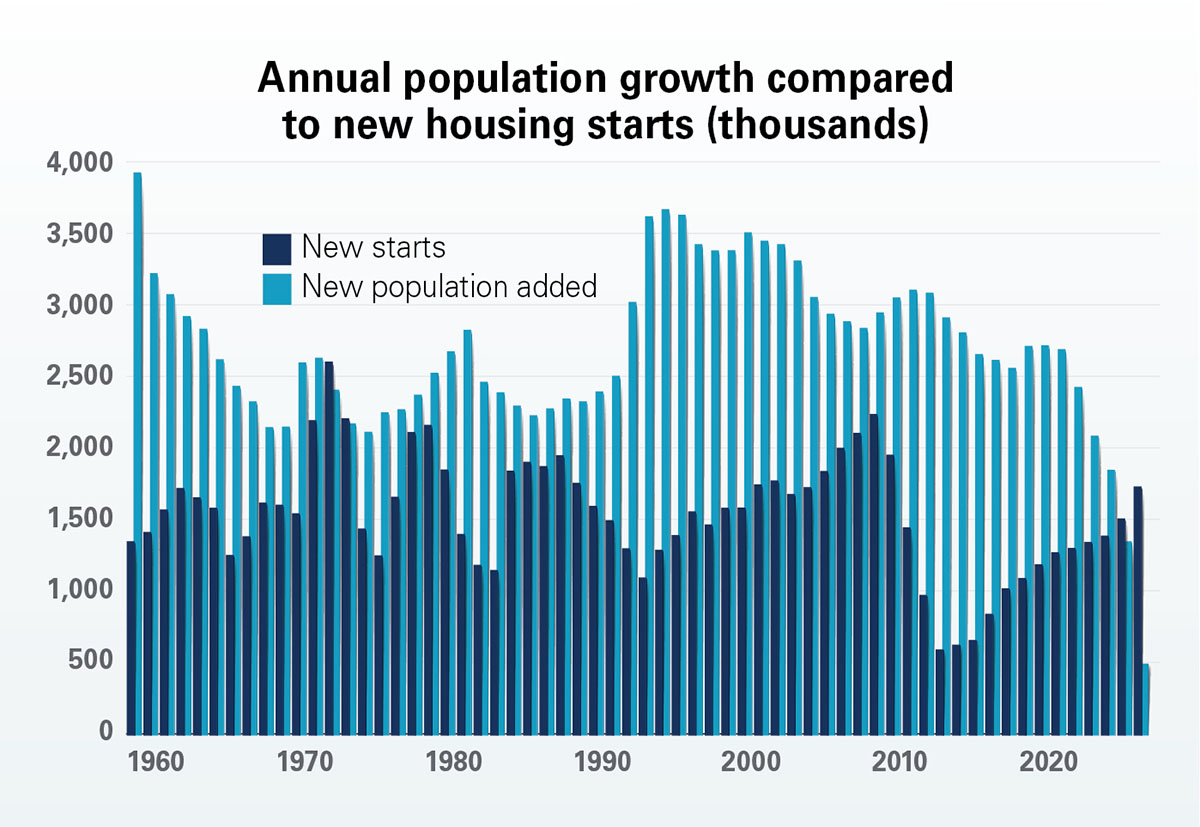

For anyone concerned about the availability and affordability of housing, this is bad news. The U.S. is currently in the midst of a housing shortage in the sense that builders aren’t building enough to keep up with population growth. And now, it appears that the short-lived boom in construction that launched in recent years will soon be over.

The combination of the boom-bust cycle and mounting government regulations driving up the cost of construction will further drive up the cost of living for ordinary Americans.

A tale of bust and boom

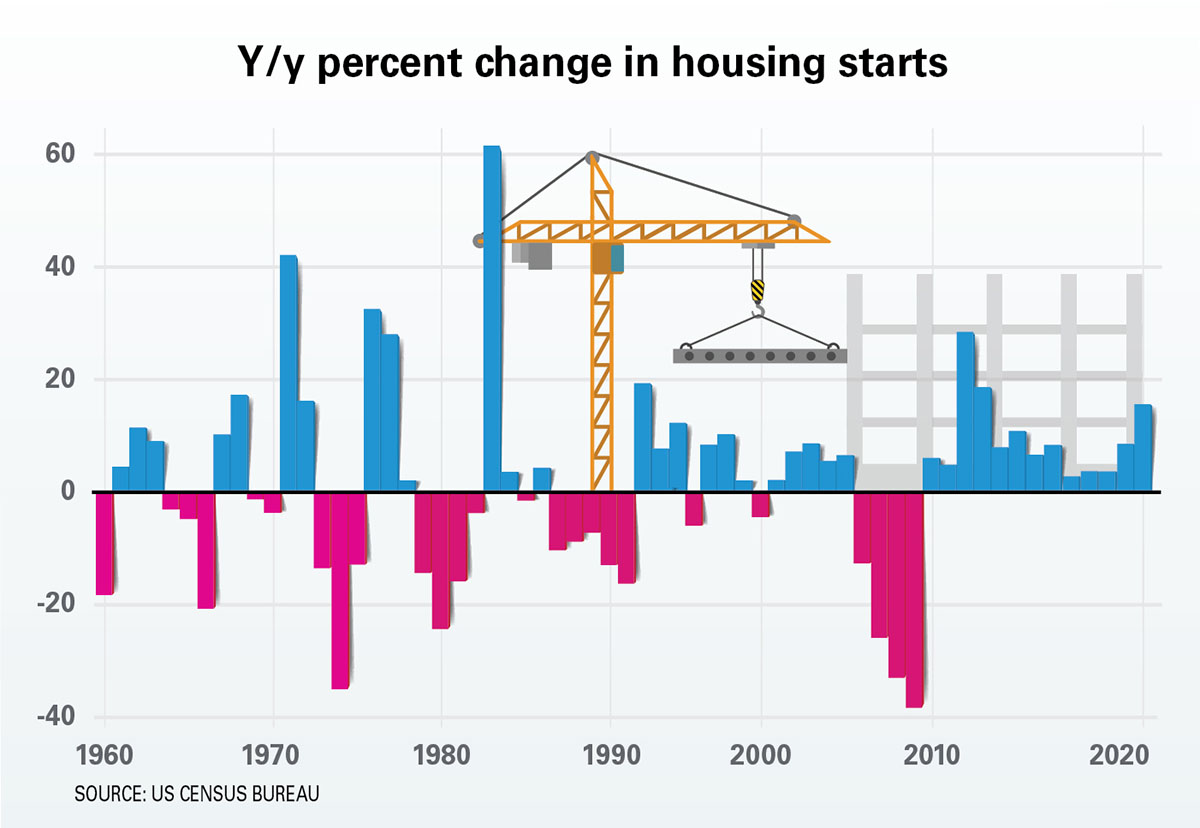

New housing construction has always been sensitive to business cycles. Over the past sixty years, it’s not hard to find annual swings in construction growth ranging from negative 20 percent to positive 20 percent.

Moreover, the negative swing on housing construction in the years surrounding the 2008 financial crisis were especially severe. Construction began to head downward in 2006, with a drop of 12 percent. This was followed by three years of even bigger declines, culminating in a 38 percent drop in 2009.

New housing construction did not return to the post-1990 average again until 2020.

In other words, the end of the housing bubble in 2009 had an enormous impact on the industry and led to more than a decade of below-average home production.

In spite of enormous amounts of new money creation, stimulus, and ultralow interest rates, the home construction industry did not bounce back. As noted in National Public Radio earlier this year, the slow pace of new housing construction did not start with the current economic cycle but dates to an earlier easy-money-induced bubble:

The roots of the problem go back much further—to the housing bubble collapse in 2008.

“What I call a bloodbath happened,” said builder Emerson Claus. It was the worst housing market crash since the Great Depression. Many homebuilders went out of business. Claus was building houses in Florida when the bottom fell out.

“A lot of my tradespeople found other work, went and got retrained for new jobs in law enforcement, all sorts of jobs,” says Claus. “So the workforce was somewhat decimated.”

A few years later, as Americans started buying more homes again, building stayed below normal. And that slump in building continued for more than a decade. Meanwhile, the largest generation, the millennials, started to settle down and buy houses.

This trend was then only made worse by the shipping and logistical bottlenecks brought on by the government-imposed covid lockdowns. These have meant a shortage of lumber, appliances, electrical equipment, and cabinetry. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) concluded in June that “shortages of materials are now more widespread than at any time since NAHB began tracking the issue in the 1990s.”

The role of monetary “stimulus”

Monetary stimulus has fueled shortages in both labor and supplies by driving both business and consumer demand to new heights. Yet since this demand is based on the appearance of newly printed money, and not on rising real wealth or productivity, we’re seeing more demand for a stagnating supply of goods and services.

The result has been less building even as the population has continued to grow. The result, of course, has been a higher cost of living—just as we would expect from an inflationary boom.

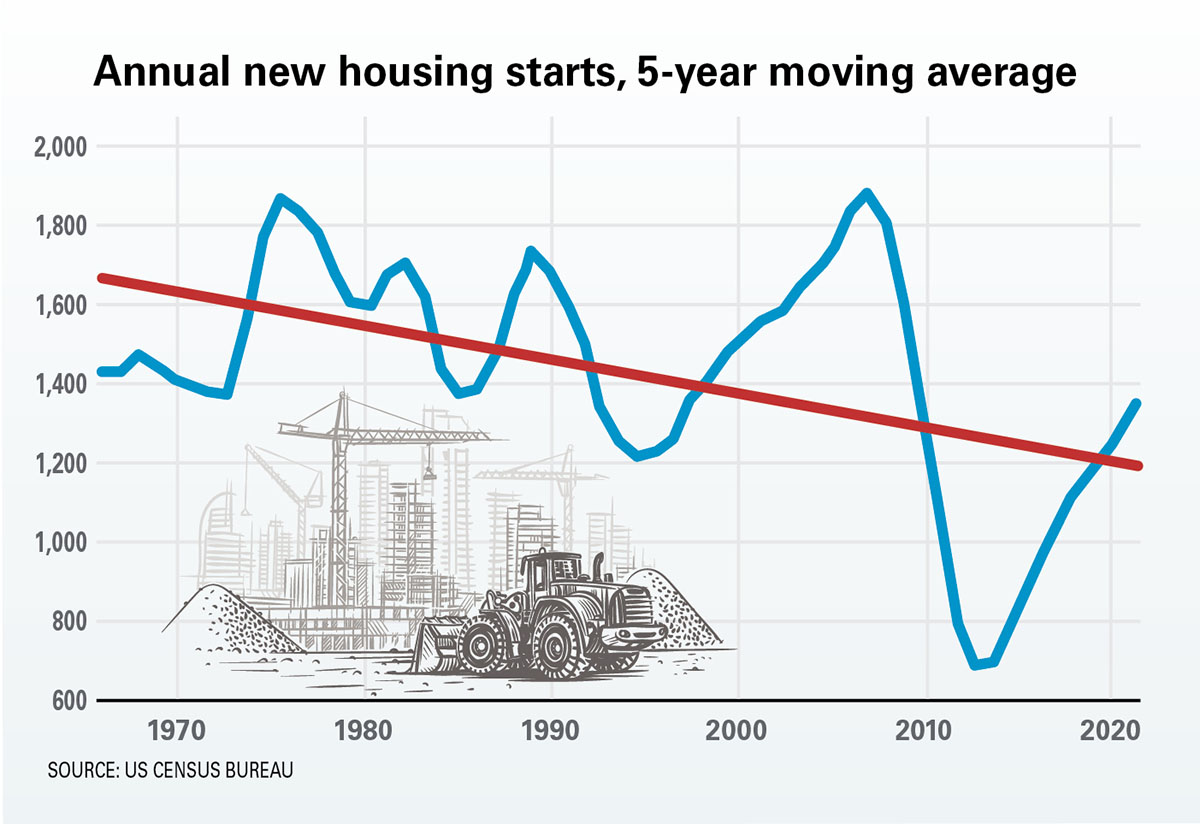

The data on housing starts and population backs up the anecdotal evidence. For example, if we look at annual housing starts totals, the trend has been downward since 1960. Beginning in 1983, every new trough in the housing construction downcycle has been lower than the one before it.

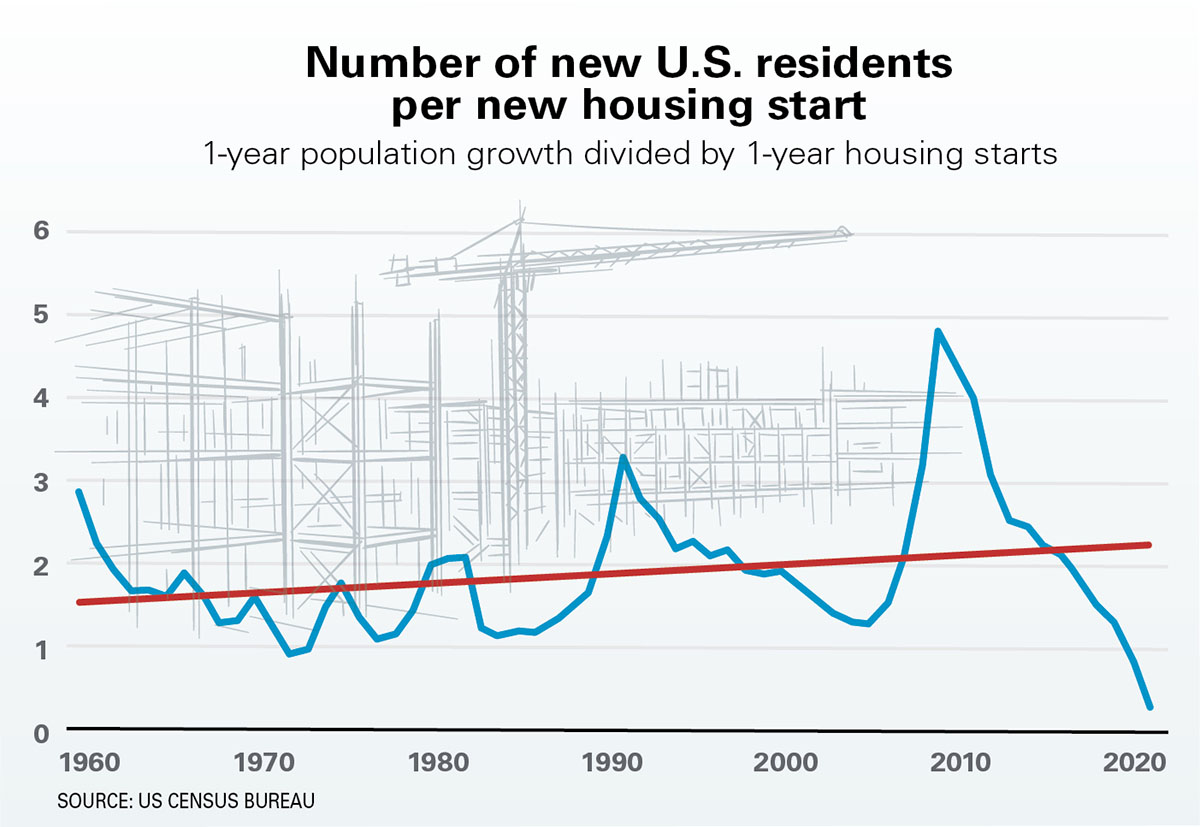

This has only been slightly mitigated by slowing population growth. We have seen an upward trend in the number of new residents per housing start even as the size of the U.S. household has fallen. In other words, the number of new residents per new housing start has grown over time. From the 1960s through the 1980s, the average number of new residents per housing start in the U.S. was approximately 1.6. Since 1990, on the other hand, the average has been 2.2. Since 2008, the average has been 2.5. So, there are progressively fewer new housing starts per person.

After new housing construction began to collapse in 2006, the number of new residents per new housing unit surged to nearly 5, a new high.

On the other hand, it is true that in 2020 and 2021, new housing construction reached the highest levels seen since 2007. Moreover, the gap between new residents and new housing was eliminated. This was thanks to a sizable decline in population growth created by covid-era border closures and a fall in fertility rates. Thus, the number of new residents per new housing unit then collapsed below 1 for the first time in decades.

But this trend is unlikely to continue, since “after a construction boom in the second half of 2020 and 2021, the home building sector is contracting.” Population growth is also returning to more normal rates. The gap between new population and new units will already be growing again in 2023. It does not look like boom of the last eighteen months will be enough to reverse the worsening situation in housing production.

What can be done to reverse the trend? The Mises Institute has identified some ways that state and local regulation has driven up the cost of construction, thus limiting the total number of units produced. Many of these regulations will only continue to push up prices while reducing affordability for first-time buyers.

It’s also important to note the effects of repeated boom-bust cycles on total housing production. One might be tempted to assume that new rounds of monetary stimulus—say, the quantitative easing of the past decade—would easily reverse a collapse in housing construction and bring new highs in housing production.

That is not what has happened, however. Rather, relentless monetary stimulus since 2008 has not been sufficient to address the effects of malinvestment and regulatory costs over the past twenty years.

Over the past six months, new housing starts have flatlined compared to 2021, and we may even see housing starts end 2022 down. The result is a continuation of an ongoing decline in housing production. Not even the runaway money printing of the past two years has been enough to bring home construction back to what was more normal before the housing bubble and resulting financial crisis.

Excerpt Ryan McMaken, The Mises Institute