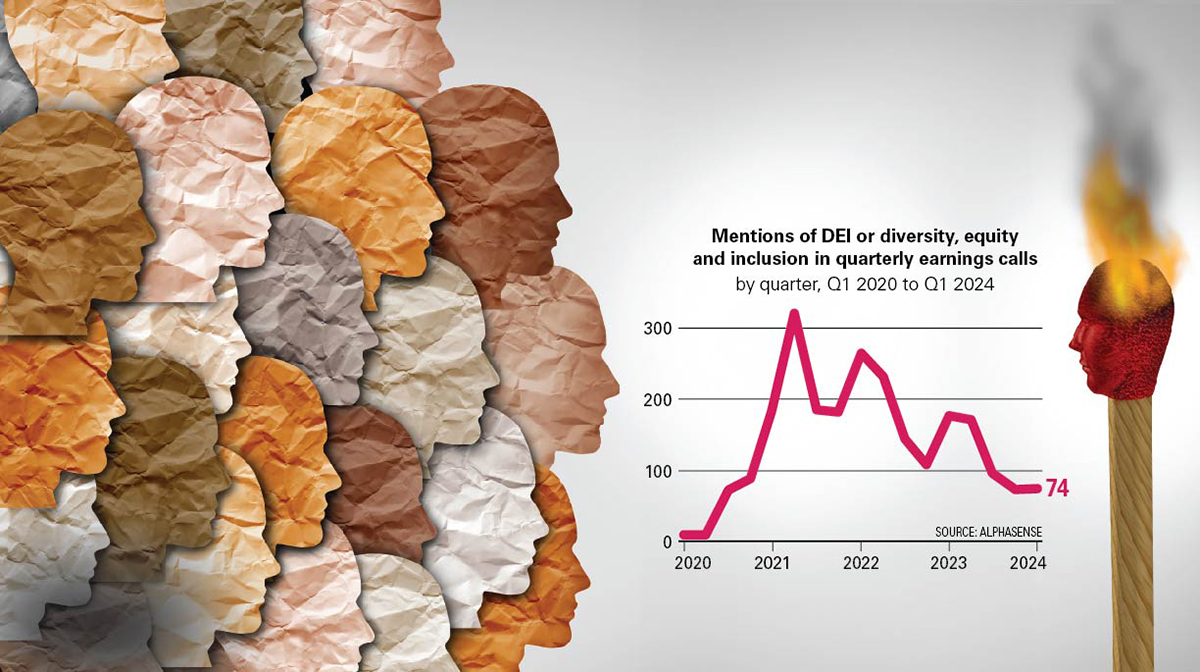

Diversity, equity and inclusion, or DEI, was the hot thing in corporate America a few years ago. Now: not so much.

Why it matters: The business community, long averse to political risks or controversies, backed away from DEI programs over the past two years in the wake of widespread attacks from lawmakers.

The big picture: Companies that never cared much about DEI, or that fear lawsuits over programs, are using the moment to back away. Others are sticking with these efforts but doing it quietly.

Between the lines: Some business leaders are increasingly reluctant to speak publicly about the subject, but behind the scenes they’re fed up with DEI, Johnny Taylor, president of the Society for Human Resource Management said in a January interview with Axios.

“The backlash is real. And I mean, in ways that I’ve actually never seen it before,” he said. “CEOs are literally putting the brakes on this DE&I work that was running strong” since George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 pushed businesses into action.

Flashback: After George Floyd, the chief diversity officer role “was the hottest position in America,” says Kevin Clayton, senior vice president, head of social impact and equity for the Cleveland Cavaliers.

Companies were hiring for these positions “out of guilt,” he said, noting that in 2020 he was pursued by more than a dozen employers.

But some CEOs are feeling like they didn’t hire well for these roles, bringing on people with civil rights backgrounds instead of more corporate expertise, said Taylor, of SHRM.

State of play: Some businesses are cutting back funding, trimming DEI staff—and even considering pulling back on things like employee resource groups comprised of workers of various races, ethnicities or interests.

And some are changing programs designed to support women and people of color because of lawsuits—many have been filed over these programs, more than 20 by Stephen Miller’s America First Legal. And other companies worry about litigation.

Comcast expanded a small business grant program called Rise, for “Representation, Investment, Strength and Empowerment,” last year to include entrepreneurs of all backgrounds.

The company’s 2020 press release about Rise discussed advancing black businesses. But in 2022, Comcast was sued by an anti-DEI group that alleged the program discriminated on the basis of race.

That suit settled in late 2022, and the following year the Rise press release contained no language about race.

Goldman Sachs opened up its “Possibilities Summit” for black college students to include white students; Bank of America broadened internal programs to “include everyone,” as Bloomberg reported in March.

“The seemingly small changes—lawyerly tweaks, executives call them—are starting to add up to something big: the end of a watershed era for diversity in the U.S. workplace, and the start of a new, uncertain one,” per Bloomberg.

What they’re saying: “I’m very disappointed and concerned about a lot of corporations that are not fighting and are not continuing these critical programs,” says Elizabeth Gore, president of Hello Alice, a fintech that serves small businesses.

Her company is fending off a lawsuit, filed by America First Legal, over a small business grant program that’s aimed at helping black-owned trucking companies.

Meanwhile: There are still companies committed to the principles behind DEI—the idea of hiring people from diverse backgrounds, figuring out how to foster inclusive workplaces and treating people fairly.

But they’re less likely to use those initials. Same with ESG—short for environmental, social and governance.

“You can kind of get your programs growing,” without using the letters, Bruce Van Saun, chairman and CEO of Citizens Financial Group, said.

Instead, Van Saun said leaders can talk about their commitment to diversity and inclusion, so that everybody feels that their voice is listened to and respected. “We want to make sure that we don’t trigger somebody with some of these words.”

The bottom line: Companies started caring about diversity a lot more after a flurry of lawsuits—with employees alleging race and sex discrimination—in the 1990s and early 2000s, as explained in “Why Diversity Programs Fail,” by Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev in Harvard Business Review.

Now a new kind of litigation risk is sending them in the other direction.