In August 2005, a little-known financial analyst named Richard Bove issued an eight-page report for Punk, Ziegel, and Company, a boutique investment bank based in New York City.

The report, titled “This Powder Keg Is Going to Blow,” noted that federal mortgage policies, including agencies like the Federal Housing Administration that “guaranteed the banks against any loss that would come from the new 20-year mortgages,” had created a housing bubble.

“According to the Bureau of Census, 12.8 percent of the housing in this country is standing empty,” Bove wrote. “There is no precedence [sic] for this in the historical numbers. The percent of empty housing has simply never been this high.”

Bove was accused of being “nuts” after he published his report, but events soon proved his analysis right.

The housing market was way over-leveraged and would soon trigger the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis.

Nearly twenty years later, Bove has made another prediction.

“The dollar is finished as the world’s reserve currency,” the 83-year-old told the New York Times in a recent interview, days after he announced his retirement on Bloomberg TV.

Bove didn’t offer a lengthy explanation on why he believed the dollar’s days as the world’s favored reserve currency were numbered, though he cited the likelihood of China eventually surpassing the US economy and the decline of American manufacturing as catalysts.

Not everyone agrees with Mr. Bove (whose name is pronounced “boe-VAY”).

Earlier this year, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said he expects the dollar to remain the favored global currency for the foreseeable future, a position it has held since the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement.

The agreement refers to Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, where delegates from more than forty countries met near the end of World War II. The goal of the meeting was to establish a new global financial framework, which is precisely what happened.

Instead of returning to the gold standard—an idea that was shunned since most countries had spent their gold reserves during the war—the dollar was essentially made the world’s official currency.

Instead of each country holding and transacting with one another using gold, they switched to holding U.S. dollars in their reserves (hence the term reserve currency).

At a surface level, there was a certain sense to the decision. The U.S. had accumulated most of the world’s gold—an estimated 70 percent, according to the International Monetary Fund—during the 1940s, since America had supplied the Allies with most of their weapons and supplies during the war.

So at Bretton Woods, leaders agreed to peg national currencies to the gold-backed U.S. dollar instead of gold; and for the next quarter-century, central banks could redeem their U.S. notes and securities in exchange for the precious metal.

That changed in 1971, however, when President Nixon ordered an end to the dollar’s convertibility to gold—most of which had been spent to finance the Vietnam War and LBJ’s Great Society—as part of his wage and price control policy. This marked the end of the Bretton Woods Agreement and the beginning of the era of fiat money, legal tender by government decree that is not backed by a physical commodity like gold or silver.

Despite the poor historic record of fiat money (more on that in a minute), many would argue Nixon’s experiment proved to be a success, even if the buying power of the dollar has steadily declined since (and resulted in a surge of income inequality and fueled the growth of the administrative state). After all, a half-century after Nixon’s order, the U.S. dollar is at least still the world’s official reserve currency… for now.

But those last two words are key.

Evidence shows bears like Bove may be on to something regarding the future of the dollar.

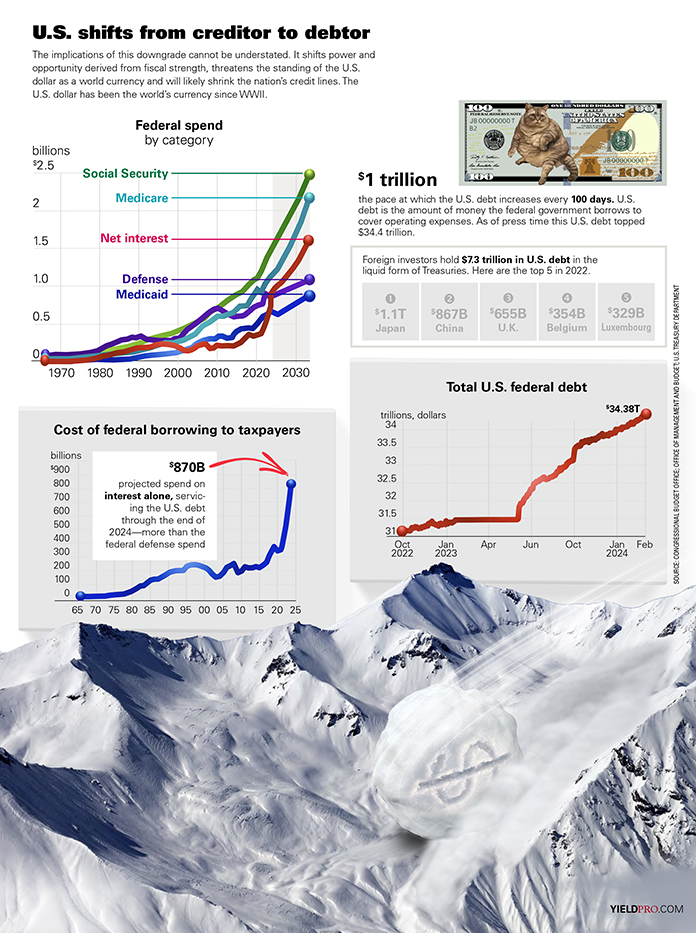

A recent analysis from JP Morgan concluded that the dollar’s “hegemony is in question,” citing foreign exchange reserves data that show “the dollar’s share has declined to a record low of 58 percent.”

The reasons nations are dumping dollars as a reserve currency are no doubt complicated and manifold, and likely include the U.S. decision to freeze hundreds of billions of dollars held by Russia following its invasion of Ukraine. That decision, BNY Mellon strategist Geoffrey Yu told Reuters in December, has left many nations wondering, “What if you fall on the wrong side of sanctions?”

Geopolitics aside, there was always a danger of tethering global finance to fiat money.

Fiat money has an infamous reputation in American history, and for good reason. America’s first experiment with unbacked paper money—the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1690—ended in disaster, as did several fiat experiments during the Revolutionary War that nearly cost the Colonials the war.

This is likely one reason America’s Founding Fathers feared and detested fiat money.

George Washington said unbacked paper money was all but certain to “ruin commerce, oppress the honest, and open the door to every species of fraud and injustice.”

Thomas Jefferson agreed.

“Paper is poverty,” the Sage of Monticello observed in 1788. “It is only the ghost of money, and not money itself.”

Perhaps nobody said it better than James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, who called paper money “unjust.”

“It is unconstitutional, for it affects the rights of property as much as taking away equal value in land,” Madison said, as author Judy Shelton noted in her book Money Meltdown (1994).

Madison understood that expanding the money supply was akin to a tax—”the most universal tax of all,” in the words of economist Thomas Sowell—and evidence shows political leaders have hardly exercised this enormous power responsibly.

A look at the money supply reveals that leaders in Washington have grown addicted to expanding it to finance their agendas—primarily wars, bureaucracy, and the welfare state. As a result, the dollar has lost roughly 87 percent of its value since 1971. Meanwhile, the national debt is expected to reach $144 trillion by 2053, according to the Congressional Budget Office, which will take an even greater toll on the dollar.

This might not be the only reason the sun may be setting on the dollar’s global hegemony. But it’s certainly one of them.

If the dollar does crash, Richard Bove can once again say, “I told you so.”